Essentials of Diagnosis

- Joint pain brought on and exacerbated by activity and relieved with rest.

- Stiffness that is self-limited upon awakening in the morning or when rising from a seated position after an extended period of inactivity.

- Absence of prominent constitutional symptoms.

- Examination notable for increased bony prominence at the joint margins, crepitus or a grating sensation upon joint manipulation, and tenderness over the joint line of the symptomatic joint.

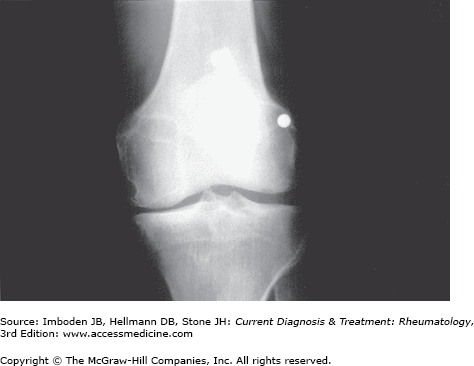

- Diagnosis supported by radiographic features of joint-space narrowing and spur (or osteophyte) formation.

General Considerations

Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of arthritis in the adult American population and affects an estimated 27 million people in the United States. Joint pain is a frequent symptom that often prompts a patient to seek medical attention; osteoarthritis figures prominently in the differential diagnosis. The challenge for clinicians is to identify correctly the cause of the patient’s pain and to initiate appropriate therapy, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic. Synonymous with degenerative joint disease, osteoarthritis is characterized by joint pain related to use, self-limited morning stiffness, an audible grating sound or crepitus on palpation, the presence of tenderness over the affected joint on palpation, and frequently reduction in joint range of motion.

Characteristic sites of involvement in the peripheral skeleton include the hand (distal interphalangeal [DIP] joint, proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joint, and first carpometacarpal joint) (Figure 43–1), knee (Figure 43–2), and hip (Figure 43–3). Constitutional symptoms are absent. The diagnosis of osteoarthritis can usually be made easily and confidently based on the history and examination alone. The bedside diagnosis of osteoarthritis can be supported by plain radiography.

Figure 43–1.

Radiograph of a hand showing osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal (DIP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and first carpometacarpal (CMC) joints. Note the joint-space narrowing of the DIP and PIP joints compared to the metacarpophalangeal joints, as well as the bony sclerosis (eburnation) of all joints involved by the osteoarthritis process.

Epidemiology

At the population level, osteoarthritis results in substantial morbidity and disability, particularly among the elderly. It is the leading indication for several hundred thousand knee and hip replacement surgeries performed each year in the United States. Therefore, much effort has been invested in improving the understanding of the epidemiology of this disorder, including identifying the risk factors that predispose persons to osteoarthritis, especially ones that are reversible or modifiable.

Several factors heighten the risk of incident osteoarthritis, including age, gender, joint injury, and obesity. Although the clinical manifestations of osteoarthritis can begin as early as the fourth and fifth decades of life, the incidence of osteoarthritis continues to increase with each decade of age. Moreover, women in their 50s, 60s, and 70s have a greater prevalence of osteoarthritis in the hands and knees than do men. Osteoarthritis among blacks is more severe and has greater impact on disability than in whites. Genetics probably plays a role in increasing the vulnerability of some joints to disease. The influence of genetics on disease occurrence is significant and usually joint specific. For example, hip osteoarthritis runs in families but these families do not have an increased risk of osteoarthritis in other joints.

Trauma to a pristine joint such as a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament or torn meniscus increases the risk of later osteoarthritis at that joint site. Incidental and usually asymptomatic meniscal tears are common in middle aged and elderly men and women and increase the risk of knee osteoarthritis. Obese women and men are at high risk for knee osteoarthritis and have a modest increase in risk for hip osteoarthritis. This increase in risk is due mostly to the excess load across weight-bearing joints conferred by obesity and, at least for women, the risk is proportional to the degree of overweight. For knee osteoarthritis, weight loss in middle age may lower this risk.

Pathogenesis

Osteoarthritis is a disease in which most or all of the joint structures are affected by pathology. The defining tissue affected is the thin layer of hyaline articular cartilage interposed between the two articulating bones. This avascular tissue becomes worn away, especially in areas of injury. There is also degeneration of fibrocartilaginous structures like the meniscus, sclerosis of underlying bone, growth of osteophytes at the joint margin, weakness and atrophy of muscles that bridge the joint, ligamentous laxity and disruption and, in many joints, synovitis. With focal cartilage loss on one side of the joint and bony remodeling there, malalignment across the joint can develop, increasing focal transarticular loading and causing further damage to cartilage and underlying bone. Both subtle chronic and flagrant acute injuries can start this disease process. Cartilage matrix turnover, spurred by daily loading across the joint, can replenish cartilage, but as a consequence of genetic abnormalities, age, and other metabolic factors not yet fully understood, some cartilage is especially vulnerable to loading that for normal cartilage, may be well tolerated.