Chapter 14 General Posttransplantation Care and Complications Cadaveric versus Living Donor Renal Transplantation Indication of Renal Function Posttransplant Postoperative Care and Complications Indication of Liver Function Posttransplant Postoperative Care and Complications Physical Therapy for Liver Transplant Recipients Indication for Pancreas Transplant Enteric Drainage versus Bladder Drainage Indication of Pancreatic Function Posttransplant Pancreatic Islet Cell Transplantation Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation Orthotopic and Heterotopic Heart Transplantation Indication of Cardiac Function Posttransplant Postoperative Care and Complications General Physical Therapy Guidelines for Transplant Recipients The objectives for this chapter are to provide information on the following: 1 The transplantation process, including criteria for transplantation, organ donation, preoperative care, and postoperative care 2 Complications after organ transplantation, including rejection and infection 3 The various types of organ transplantation procedures 4 Guidelines for physical therapy intervention with the transplant recipient • Impaired Aerobic Capacity/Endurance Associated With Deconditioning: 6B • Impaired Aerobic Capacity/Endurance Associated With Cardiovascular Pump Dysfunction or Failure: 6D • Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Ventilatory Pump Dysfunction or Failure: 6E • Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Respiratory Failure: 6F Please refer to Appendix A for a complete list of the preferred practice patterns, as individual patient conditions are highly variable and other practice patterns may be applicable. With advances in technology and immunology, organ and tissue transplantation has become a more standard practice. There were 28,053 organ transplants performed in the United States in 2012.1 Physical therapists are frequently involved in the rehabilitation process for pretransplant and posttransplant recipients.2 Owing to limited organ donor availability, physical therapists often treat more potential recipients than posttransplant recipients. Patients awaiting transplants often require admission to an acute care hospital as a result of their end-stage organ disease. They may be very deconditioned and may benefit from physical therapy during their stay. The goal of physical therapy for transplant candidates is conditioning in preparation for the transplant procedure and postoperative course, and increasing functional mobility and endurance in an attempt to return patients to a safe functional level at home. Some transplant candidates may be too acutely sick and may no longer qualify for transplantation during that particular hospital admission. These patients are generally unable to work and may need assistance at home from family members or even require transfer to a rehabilitation facility. The kidney, liver, pancreas, heart, lung, and intestine are organs that are procured for transplantation. The most frequent of those are the kidney, liver, and heart.3 Double transplants, such as liver-kidney, kidney-pancreas, and heart-lung, are performed if the patient has multiorgan failure. Intestinal transplants are not addressed in this text because they are performed in much smaller numbers, with only 106 transplants in 2012.1 Candidates for this procedure include individuals with various disorders involving poor intestinal function and who are unable to be maintained with other nutritional support. In addition to these solid organ transplants, stem cell transplants that involve the replacement of abnormal cells with healthy cells are discussed. Transplantation is offered to patients who have end-stage organ disease for which alternative medical or surgical management has failed. The patient typically has a life expectancy of less than 1 to 3 years.4–6 Criteria for organ recipients vary, depending on the type of organ transplant needed and the transplant facility. The basic criteria for transplantation include the following7: • The presence of end-stage disease in a transplantable organ • The failure of conventional therapy to treat the condition successfully • The absence of untreatable malignancy or irreversible infection • The absence of disease that would attack the transplanted organ or tissue In addition to these criteria, transplant candidates must demonstrate emotional and psychological stability, have an adequate support system, and be willing to comply with lifelong immunosuppressive drug therapy. Other criteria, such as age limits and absence of drug or alcohol abuse, are specific to the transplant facility. To determine whether transplantation is the best treatment option for the individual, all transplant candidates are evaluated by a team of health care professionals consisting of a transplant surgeon, transplant nurse coordinator, infectious disease physician, psychiatrist, social worker, nutritionist, and sometimes a physical therapist. The patient undergoes many laboratory and diagnostic studies during the evaluation process. Acceptable candidates for organ transplantation are placed on a waiting list. Waiting times for an organ may range from days to years depending on the organ and an individual’s medical status.3 Improvements in the medical management of transplant recipients, including immunosuppressants and postoperative care protocols, have increased survival rates. As a result, organs are now being offered to recipients that were previously considered “high-risk,” including older patients with multiple comorbidities and accompanying activity limitations.8 Cadaveric donors are generally individuals who have been determined to be dead by neurological criteria following severe trauma, such as from head or spinal cord injury, cerebral hemorrhage, or anoxia.9,10 Death must occur at a location where cardiopulmonary support is immediately available to maintain the potential organ donor on mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary bypass, or both in order to preserve organ viability.9 To a more limited extent, death can also be determined on the basis of circulatory criteria, and organs can be expeditiously procured after specific criteria have been met (e.g., asystole for generally between 2 and 5 minutes). However, ethical issues remain surrounding the precise determination of death and decisions to withdraw support. In addition, these organs are subject to potentially greater ischemic injury, which in turn increases the risk for delayed graft function and graft failure.3,11 Both types of cadaveric donors must have no evidence of malignancy, sepsis, or communicable diseases, such as hepatitis B or human immunodeficiency virus.7,12,13 As of April 2013, there were more than 117,000 individuals on the transplant waiting list, with more than 75,000 of those listed as medically suitable for transplant. However, there were just over 14,000 donors from January through December 2012.1 As a result, many patients die waiting for a suitable organ to become available. Numerous efforts have been undertaken to address the organ donor shortage, including educational campaigns and technological advancements. Increased use of what are termed “expanded criteria” donor (ECD) grafts is occurring with many transplants including kidney. These are organs that may have previously gone un-used due to advanced age or other complicating factors such as hypertension or death from stroke.8 Regenerative medicine entails the development of cellular, tissue, and organ substitutes to help restore function.14 Engineers continue to work on the development of implantable bioartificial organs, including an artificial kidney and lungs; however, none of these devices have yet gained approval for use in humans in the United States. Stem cell research also has the potential to provide an alternative to solid organ transplant. The goal is for immature stem cells to be directed to differentiate into specific cell types and repair or replace tissues that have been damaged because of injury. For example, stem cells have been shown in animal and a few small human studies to repair injured heart tissue and improve cardiac function.15 In the United States, organ procurement and distribution for transplantation are administered by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) under contract with the federal government. UNOS sets standards for transplant centers and teams, tissue typing laboratories, and organ procurement organizations. Organ allocation is a complex process, and UNOS policies attempt to balance justice and medical utility. Factors that are involved with determining allocation and how they are weighted in the decision making vary by organ but generally include the following1: • Tissue (histocompatibility) typing • Severity of illness/degree of medical urgency • Geographic location (distance between potential recipient and donor) The donor and recipient must be ABO blood type identical or compatible for all organ transplants.16 Tissue typing typically involves a series of several tests to determine how likely a potential recipient is to develop a rejection response with transplantation, which include: • Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing attempts to match HLAs, which are the antigens that cause most graft rejection. The better the histocompatibility match and degree of genetic similarity between the donor and the recipient, the less severe the potential rejection response. This may be performed in several ways; however, the most conventional method involves mixing a serologic sample of the potential recipient’s lymphocytes with a standard panel of antisera and observing for lymphocytotoxicity.17 • White cell cross-matching is performed by mixing the lymphocytes from the donor with the serum from the recipient and then observing for immune responses. A negative cross-match indicates no antibody reaction and that the recipient’s antibodies are compatible with the donor. A negative cross-match is required for successful kidney and kidney-pancreas transplants.18 Although pretransplant tissue typing is ideal, it is not always performed due to insufficient time. The time that an organ remains viable after it is recovered varies by organ. Average viability times range from 4 to 6 hours for heart and lungs, 24 hours for pancreas, 24 to 30 hours for liver, and 48 to 72 hours for kidneys.3 When there is insufficient time, the other factors become the major considerations.17,19 For example, in lung transplant, the Lung Allocation Score (LAS) is used to estimate the severity of illness and chance for survival to assist with allocation.1 Postoperative care for living donors is similar to that for any patient who has undergone major abdominal or cardiothoracic surgery. These patients are taken off mechanical ventilation in the recovery room and transferred to the general surgery or transplant ward. Vital signs and blood counts are monitored closely for possible postoperative bleeding. Patients are usually out of bed and ambulating by postoperative day 1. On average, the duration of donor hospitalization may range from 1 to 2 days for a kidney donor to 8 days for a simultaneous pancreas-kidney (SPK) donor.18,20 Physical therapists are rarely involved with donors, but may become involved if complications arise affecting the donors’ functional mobility. Once an organ is transplanted, the postoperative care focuses on the monitoring and treatment of the following21: General postoperative care for transplant recipients is also similar to the care patients receive after major abdominal or cardiothoracic surgery. Kidney and liver transplant recipients are often taken off of mechanical ventilation before leaving the operating room.22,23 Most other solid organ recipients are transferred from the operating room to the surgical intensive care unit, where they are weaned from mechanical ventilation (extubated) within 24 to 48 hours.3,16,24,25 Once extubated and hemodynamically stable, recipients are transferred to specialized transplant floors. The nursing staff monitors the recipient closely for signs and symptoms of infection and rejection, which are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the first year after transplantation. Rejection, or the tendency of the recipient’s body to reject anything that is “nonself,” is one of the leading problems with organ transplantation. This is actually a normal immune response to invasion of foreign matter, the transplanted organ or tissue. Some degree of rejection is normal; however, if the patient is not treated with immunosuppressive drugs, the donor organ will be completely rejected and cease to be viable.3 Transplant recipients must receive immunosuppressants for the rest of their lives to minimize rejection of their transplanted organs. The pharmacologic agents most often used to prevent organ rejection include double or triple drug therapy, which allows use of smaller doses of individual drugs.26 These immunosuppressive drugs decrease the body’s ability to fight infection. A delicate balance must be reached between suppressing rejection and avoiding infection. Insufficient immunosuppression may result in rejection that threatens the allograft and patient survival, whereas excessive immunosuppression increases the risk of infection and malignancy.21 If detected early, rejection can be minimized or reversed with an increase in daily doses of immunosuppressive drugs. Many different factors influence the combination of drugs used posttransplant including the individual patient’s condition, organ transplanted, transplant center–specific practices, and recent literature. There are three general approaches to posttransplant immunosuppression26: • Induction immunosuppression: Encompasses high-dose immunosuppressive medications given to prevent acute rejection immediately after transplantation (usually only in the first 30 days) • Maintenance immunosuppression: Includes all medications used for long-term immunosuppression • Antirejection immunosuppression: Includes all immunosuppressive medications given for managing a specific acute rejection episode at any point posttransplantation The main classes of drugs used for transplant immunosuppression include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites, target of rapamycin inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and polyclonal anti-lymphocyte antibodies. Individual drug classes have different mechanisms that include inhibition of gene transcription, DNA and RNA production, T-cell activation and proliferation, and lymphocyte and antibody production.27 Please refer to Chapter 19 for additional pharmacology information and physical therapy implications for each medication. Hyperacute rejection is characterized by ischemia and necrosis of the graft that occurs from the time of transplant to 48 hours after transplant.7 It is believed to be caused by cytotoxic antibodies present in the recipient that respond to tissue antigens on the donor organ. The manifestations of hyperacute rejection include general malaise and high fever. Rejection occurs before vascularization of the graft takes place. Plasmapheresis may be used to attempt to remove circulating antibodies from the blood. However, usually hyperacute rejection is unresponsive to treatment, and removal of the rejected organ with immediate retransplantation is required.3,17,29 Acute rejection is a treatable and reversible form of rejection that typically occurs within the first 3 months to 1 year after transplantation. However, changes in the immunosuppressive management may also cause later acute rejection episodes.3 Almost every patient has some degree of acute rejection after transplantation. It may be due to an antibody-mediated immune response and/or a T-cell–mediated immune response. More commonly, T lymphocytes detect foreign antigens from the graft, become sensitized, and set the immune response into action. Phagocytes, which are attracted to the graft site by the T lymphocytes, damage the inner lining of small blood vessels in the organ. This causes thrombosis of the vessels, resulting in tissue ischemia and eventual death of the graft if left untreated.3,12 The first signs of acute rejection may be detected within 4 to 10 days postoperatively.7,12,17 The actual manifestations of rejection vary with the affected organ. General signs and symptoms of acute rejection include the following1,3,12: • Fever, chills, sweating, body aches/pains • Swelling and/or tenderness at the graft site • Nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, loss of appetite • Dyspnea, irregular heart beat, increased blood pressure • Sudden weight gain (6 lb in less than 3 days) • Abnormal laboratory findings (dependent on organ): electrolyte imbalances, increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels, increased bilirubin and liver enzymes (alanine transaminase [ALT], aspartate transaminase [AST]), increased urine amylase Chronic rejection of the graft occurs after the first few months of transplantation and is characterized by gradual and progressive deterioration of the graft. It is believed to result from a combination of B-cell–mediated and T-cell–mediated immunity, frequent episodes of acute rejection, and also infection. Persistent inflammation leads to graft necrosis and deterioration in function. Increasing immunosuppressive medications may slow the process, but it cannot stop chronic rejection, and eventually retransplantation is required. Chronic rejection presents differently depending on the transplanted organ. Individuals who have undergone kidney and liver transplants may present with a more gradual rise in lab values (i.e., creatinine, BUN, bilirubin, liver function tests [LFTs]) compared to what is seen in acute rejection.7,12,30 In patients with cardiac transplants, coronary allograft vasculopathy may occur in which there is accelerated graft atherosclerosis or myocardial fibrosis leading to myocardial ischemia and infarction.7 Chronic rejection in patients with lung transplants is manifested as bronchiolitis obliterans with symptoms of increasing airflow obstruction.4,5 In patients with pancreas transplants, the pancreatic vessels thicken, leading to fibrosis, and there is a decrease in insulin secretion with resultant hyperglycemia.7 Suppression of the immune response prevents rejection of the transplanted organ; however, the recipient is more susceptible to bacterial, fungal, and viral infections. Infection is one of the leading causes of critical illness, hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality following organ transplant.31 The high risk of infections posttransplant requires that recipients be given antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal medications prophylactically. Active infections are treated with a reduction of immunosuppressants and addition of other medications targeting the pathogen.3 Please refer to Chapter 19 for information about specific medications used to treat infections. An overview of the timeline for infection after organ transplant is shown in Figure 14-1. FIGURE 14-1 Changing timeline of infection after organ transplant. (Data from Fishman JA: Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients, N Engl J Med 357:2601, 2007. In Auerbach PS: Wilderness medicine, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2012, Mosby/Elsevier.) General signs and symptoms of infection include the following18: Renal or kidney transplant is the most common organ transplant procedure.3 In 2012, there were 16,487 recorded kidney transplants in the United States.1 The goal of renal transplantation is to restore normal renal function to patients with irreversible end-stage renal failure. The most frequent causes of end-stage renal disease requiring transplantation include the following9,17: Contraindications to renal transplantation include the following17: Kidney transplants may be cadaveric or living donor. Cadaveric kidneys may be maintained for as long as 72 hours before transplantation and, as a result, are the last organs to be harvested. Although less commonly performed, living donor kidney transplants are preferred to cadaveric transplantation. Most living donor nephrectomies are performed laparoscopically with a 2- to 3-inch incision in the lower quadrant, minimizing pain and allowing donors to mobilize quickly after surgery.1,10,32 Because the body can function well with one kidney, the kidney donor can lead a normal, active life after recovering from the surgery. There is no increased risk of kidney disease, hypertension, or diabetes, and life expectancy does not change for the donor.18 The benefits of a living donor transplant for the recipient include longer allograft and patient survival rates. According to UNOS data as of April 2013, the 5-year kidney graft survival rate is 79.8% for living donors compared to 66.6% for cadaveric donors, and patient 5-year survival rates are 90.1% and 81.8%, respectively.1 The higher success rate of the recipients of living donor transplants can be attributed to the following: potentially healthier recipients since undergoing procedure electively, more thorough pretransplant evaluation resulting in closer genetic matches, lower incidence of acute tubular necrosis (ATN) postoperatively, and lower requirement for immunosuppressive medications resulting in a lower risk for infection/malignancy.18,33 Unfortunately, a shortage of donor kidneys continues, with more than 5000 individuals removed from the waiting list due to death in 2009.1 Strategies to expand the donor pool are evolving and include the following32: • Desensitization protocols—use of intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis before transplant to modulate antibodies and reduce the recipient’s potential immune response. This may allow the use of organs that are traditionally deemed incompatible based on blood type and/or a positive cross-match. • Kidney Paired Donation (KPD)—a potential recipient with a willing but incompatible donor is matched to another incompatible donor recipient pair with reciprocal incompatibility. Donor chains that incorporate this concept are developing. The renal allograft is not placed in the same location as the native kidney. It is placed extraperitoneally in the iliac fossa through an oblique lower abdominal incision.3,10,34 The renal artery and vein of the donated kidney are attached to the recipient’s internal iliac artery and iliac vein, respectively. The ureter of the donated kidney is sutured to the bladder and a urinary catheter is placed for approximately 5 days to allow for healing.10 The recipient’s native kidney is not removed unless it is a source of infection or uncontrolled hypertension. The residual function may be helpful if the transplant fails and the recipient requires hemodialysis.34,35 The advantages of renal allograft placement in the iliac fossa include the following36: • A decrease in postoperative pain because the peritoneal cavity is not entered • Easier access to the graft postoperatively for biopsy or any reoperative procedure • Ease of palpation and auscultation of the superficial kidney to help diagnose postoperative complications • The facilitation of vascular and ureteral anastomoses, because it is close to blood vessels and the bladder Restoration of renal function is characterized by: • Immediate production of urine and massive diuresis (excellent renal function is characterized by a urine output of 800 to 1000 ml per hour)25 However, there is a 20% to 30% chance of delayed graft function, and dialysis may be required for a few days to several weeks.1,34 Dialysis is discontinued once urine output increases and serum creatinine and BUN begin to normalize. With time, normal kidney function is restored, and the dependence on dialysis is eliminated.34 Volume status is strictly assessed, and intake and output records are precisely recorded. Daily weights should be measured at the same time using the same scale. When urine volumes are extremely high, intravenous fluids may be titrated. Other volume assessment parameters include inspection of neck veins for distention, skin turgor and mucous membranes for dehydration, and extremities for edema. Auscultation of the chest is performed to determine the presence of adventitious breath sounds, such as crackles, which indicate the presence of excess volume.17 The most common signs of rejection specific to the kidney are an increase in BUN and serum creatinine, decrease in urine output, increase in blood pressure, weight gain greater than 1 kg in a 24-hour period, and ankle edema.17,18,34 A percutaneous renal biopsy under ultrasound guidance is the most definitive test for acute rejection.34ATN may occur posttransplantation because of ischemic damage from prolonged preservation, and dialysis may be required until the kidney starts to function.18 Ureteral obstruction may occur owing to compression of the ureter by a fluid collection or by blockage from a blood clot in the ureter, and may be visible on ultrasound. The placement of a nephrostomy tube or surgery may be required to repair the obstruction and prevent irreversible damage to the allograft.34 Urine leaks may occur at the level of the bladder, ureter, or renal calyx. They usually occur within the first few days of transplantation.34 Renal ultrasounds are performed to assess for fluid collections, and radionucleotide scans view the perfusion of the kidney. Other potential complications include posttransplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM); renal artery thrombosis or leakage at the anastomosis; hypertension; hyperkalemia; renal abscess or decreased renal function; and pulmonary edema.3,19,34 Thrombosis most often occurs within the first 2 to 3 days after transplantation.34 The most common cause of decreased urine output in the immediate postoperative period is occlusion of the urinary catheter due to clot retention, in which case aseptic irrigation is required.17 • Daily fluid intake of 2 to 3 liters is generally recommended for kidney transplant recipients.22,38 Therapists should assist patients in adhering to fluid recommendations from the medical team during therapy sessions. • In the immediate postoperative period, blood pressure (BP) needs to be maintained to ensure adequate perfusion to the newly grafted kidney. Therapists should check with the physician for specific parameters, but generally the systolic BP should be kept above 110 mm Hg. Kidney transplant recipients may be normotensive at rest; however, they respond to exercise with a higher-than-normal blood pressure.39 • Consistent BP monitoring for the life span of the transplant is necessary because many transplant recipients develop hypertension over time, and cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in kidney transplant recipients.40 The liver is the second most commonly recorded organ transplanted in the United States, with 6256 patients undergoing liver transplant surgery in 2012.1 Indications for liver or hepatic transplantation include the following7,41,42: • Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) resulting from an acute viral, toxic, anesthetic-induced, or medication-induced liver injury • Congenital biliary abnormalities • Confined hepatic malignancy (hepatocellular carcinoma) • Hereditary metabolic diseases (such as familial amyloid polyneuropathy) Contraindications to hepatic transplantation include the following3,30,41: • Myocardial infarction within the previous 6 months • Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease • Active alcohol use/other substance abuse (required time to be substance-free is determined by center, but is usually greater than 6 months) Patients awaiting liver transplant are often deconditioned and malnourished with resulting weakness and muscle loss due to breakdown of muscle protein and fat, which are used as alternative energy sources.43 Additionally, anasarca and/or ascites often lead to overall weight gain with associated balance impairments. The goals of preoperative physical therapy include aerobic conditioning, strength training, postural education, and maximizing functional mobility with a focus on education regarding postoperative follow-up, fall prevention, home exercise program, and lifestyle modification. Table 14-1 provides some characteristics of liver failure, their clinical effects, and their implications for physical therapy. TABLE 14-1 Medical Characteristics of Liver Failure, Their Related Clinical Effects, and Physical Therapy Implications Data from Sigardson-Poor KM, Haggerty LM: Nursing care of the transplant recipient, Philadelphia, 1990, Saunders, p 149-151; Braddom RL, editor: Physical medicine and rehabilitation, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2000 and 2007, Saunders, pp 139 and 1145; Findlay JY et al: Critical care of the end-stage liver disease patient awaiting liver transplantation, Liver Transplantation 17:496-510, 2011.

Organ Transplantation

Preferred Practice Patterns

Types of Organ Transplants

Criteria for Transplantation

Transplant Donation

Cadaveric Donors

Living Donors

Donor Shortage

Donor Matching/Allocation

General Posttransplantation Care and Complications

Postoperative Care for Living Donors

Postoperative Care for Transplant Recipients

Rejection

Types of Graft Rejection

Hyperacute Rejection.

Acute Rejection.

Chronic Rejection.

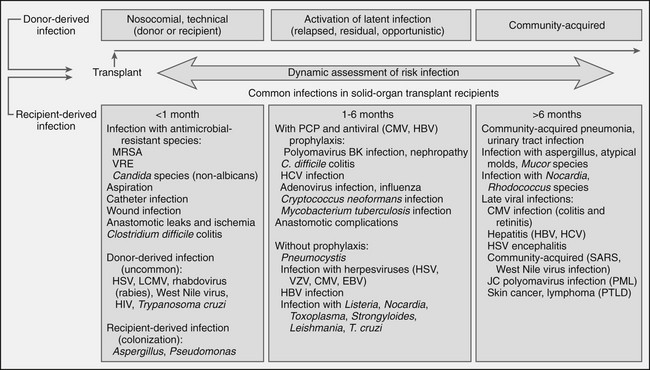

Infection

Renal Transplantation

Cadaveric versus Living Donor Renal Transplantation

Renal Transplant Procedure

Indication of Renal Function Posttransplant

Postoperative Care and Complications

Physical Therapy for Renal Transplant Recipients

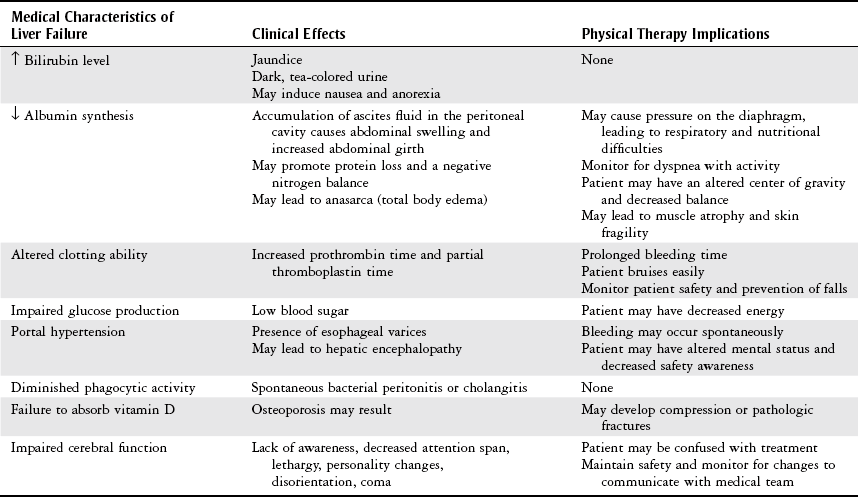

Liver Transplantation

Pretransplantation Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Organ Transplantation

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue