Operative Treatment of Radius and Ulna Diaphyseal Nonunions

John R. Dawson

Lee M. Reichel

DEFINITION

A diaphyseal forearm fracture should be treated as a nonunion if there is either no likelihood that the fracture will go on to union (ie, large segmental defect) or if the fracture has ceased to demonstrate any progression of healing.

Secondary to the advent of compression plating, the incidence of forearm nonunions is low, with rates in the radius of 2% and the ulna of 4%.7

ANATOMY

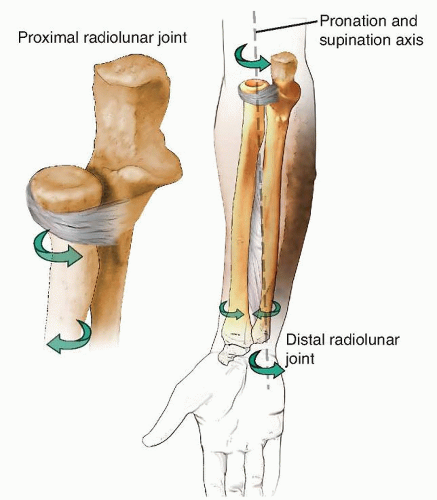

The ulna functions as a straight, stable axis around which the bowed radius rotates. The bow of the radius is apex radial and apex dorsal.

The distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ), the interosseous membrane (IOM), and the proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) are the ties that bind the two bones together (FIG 1).

There is length variability built into the relationship between the radius and ulna: the radius is at its relative longest in full supination and relative shortest during full pronation.

Despite this, there is a very close coordination of length between the two bones that is important to normal forearm function. The forearm itself can be thought of as a joint.

FIG 1 • The two bones of the forearm form a functional unit, with the axis of rotation extending from the radiocapitellar joint to the DRUJ.

Extrinsic and intrinsic hand extensors and flexors originate in the forearm as well as do the wrist flexors. Additionally, the forearm provides passage to the neural and vascular elements that give the hand its intricate function. Forearm nonunions, depending on their etiology, can result in a considerable amount of scarring that obliterates normal tissue planes and complicates surgical dissection.

PATHOGENESIS

In the case of a single-bone injury, radius or ulna, if there is any bone deficit at the fracture site, there is an increased risk of nonunion because the length stability of the uninjured bone acts as a distracting force.

Diaphyseal comminution at the fracture site increases the incidence of nonunion to 12% despite plate fixation.8 Gunshot blasts are a common mechanism which results in comminution.

Although isolated radius fractures are treated operatively to ensure reestablishment of the radial bow that is so vital to forearm rotation, isolated ulnar shaft fractures are frequently treated nonoperatively.

Even with nonoperative treatment, most ulnar fractures go on to union: Nonunion rates are around 3%.1

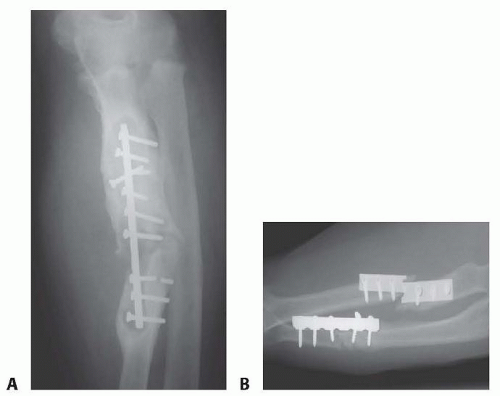

Internal fixation must be able to withstand the torsional stresses involved in forearm rotation. Inadequate fixation and poor surgical technique are a frequent cause of hypertrophic nonunion (FIG 2A).

Many of the injuries that result in nonunion involve a defect; thus, most diaphyseal nonunions of the forearm are atrophic in nature (FIG 2B).7

Open both-bone forearm fractures and ballistic injuries are frequently associated with bone loss at the fracture site.

Periosteal stripping, loss of the fracture hematoma, soft tissue and bone loss, and increased infection rate all increase the rate of nonunion.

Comminuted open fractures with loss of bone have the highest rates of nonunion.4

NATURAL HISTORY

Nonunions of the forearm do not heal without surgical intervention.

The resultant loss of stability of one or both bones unhinges the entire mechanism of forearm motion with subsequent loss of pronation and supination.

Because the movement of the PRUJ and DRUJ are intricately related to the normal length and rotational relationships between the radius and ulna, motion at these joints is affected by a forearm nonunion.

Without treatment, the deformity that results from forearm nonunion can become permanent.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Although some nonunion patients present with clear deformity, there are others whose only complaint is pain. Frequently, there is also a limitation in forearm rotation.

Additionally, limitations in wrist and finger motion are frequently present when there is significant change in ulnar variance secondary to bone shortening.

Pain may be exacerbated by use of the extremity for lifting and pushing and strength is severely impaired.

Pain may be caused by torsional stressing of the forearm.

Physical examination

Evaluate the skin and soft tissue envelope. Long-standing infected nonunions may develop draining sinuses.

Thorough vascular examination to look for any vasculopathy

Palpate the nonunion site for pain.

Stress the forearm by resisting flexion, extension, pronation, and supination.

Look for loss of motion at the elbow or wrist.

Look for a loss of pronation or supination.

Infection is always considered as a cause of nonunion, especially if the initial fracture was open or if the patient has had surgery on the affected arm.

If the patient was previously treated at another facility, be sure to clarify if there was any postoperative drainage or if antibiotics were required. Obtain the previous records if possible.

As is the case for any nonunion patient, look for host factors that affect bone healing such as tobacco use. A detailed metabolic workup should be performed that includes tests for vitamin D, albumin, pre-albumin, calcium, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), hemoglobin A1c (for diabetics), thyroidstimulating hormone (TSH), and testosterone.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs in neutral forearm rotation should be obtained of both the affected forearm as well as of the uninjured forearm. This provides a comparison view for a full evaluation of the deformity.

In the event of a questionable nonunion, computed tomography (CT) can be used to evaluate bone healing at the site in question.

CT also helps elucidate rotational deformities, the presence and extent of a synostosis, and the bony relationships of the DRUJ and PRUJ.

An infection workup should be performed in all patients. This includes an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and a complete blood count (CBC).

If laboratory tests are normal, but infection is seriously suspected, consider a technetium 99m bone scan followed by an indium 111-labeled leukocyte scan.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a biopsy of the nonunion site can also be used to evaluate for infection.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Infection

Forearm malunion

Undiagnosed PRUJ or DRUJ injury

Symptomatic implants

IOM injury

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management of a symptomatic nonunion should be reserved for patients who are poor operative candidates or noncompliant with treatment efforts. As with any nonunion, the treatment course is long and complicated and requires patience on the part of both the patient as well as the surgeon.

Patient participation is essential, and smoking cessation is required prior to repair of the nonunion. Smoking cessation should be stopped 4 weeks prior to surgery to negate the anti-inflammatory effects.

Typically, two nicotine tests 2 weeks apart prior to surgery confirms smoking cession.

Rarely, a patient will develop a stable, fibrous union that allows for pain-free function. These patients do not require an operation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The primary goal of treatment is to obtain union. Significant improvements in range of motion are not always realized. In some cases where forearm motion is taking place through the nonunion site, obtaining union can even result in loss of motion. The patient should be aware of this preoperatively.

Surgery focused on the PRUJ or DRUJ may be required to improve motion.

Previously operated wound beds have severe scarring, and there is an increased risk of neurovascular injury during surgery.

Preoperative Planning

Full-length multiplanar radiographs of both forearms should be obtained to assess for any deformity. The normal variance of the uninjured wrist should be noted in full supination.

Determination of nonunion type should be made—either hypertrophic or atrophic. This will determine what type of treatment is necessary to gain union.

If the patient is infected, a staged treatment course should be considered as well as intraoperative plans for the evaluation of the infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree