Operative Treatment of Extra-articular Phalangeal Fractures

Richard L. Uhl

Michael T. Mulligan

DEFINITION

Extra-articular fractures of the phalanges include metaphyseal and diaphyseal fractures of the proximal, middle, and distal phalanges.

Extra-articular fractures of the phalanx can range from an isolated bony injury to injuries that affect the entire soft tissue envelope, flexor and extensor tendons, and the neurovascular structures.

ANATOMY

The phalanges are the long, tubular bones of the hand that enable a functional arc of motion.

The extensor mechanism of the finger glides directly on top of the phalanges, with only a thin layer of periosteum and peritenon between bone and tendon in adults.

Fractures of the phalanges and the resultant bleeding, swelling, and scarring can greatly inhibit extensor function.

Early motion of the extensor mechanism can help minimize adhesions between bone and tendon. This is an essential principle that must be kept in mind when treating these injuries.

Hardware, particularly a plate, placed dorsally beneath the tendon may interfere with extensor tendon function. This has led many to recommend alternate fixation methods as well as advocate plate placement on the lateral aspect of the bone.

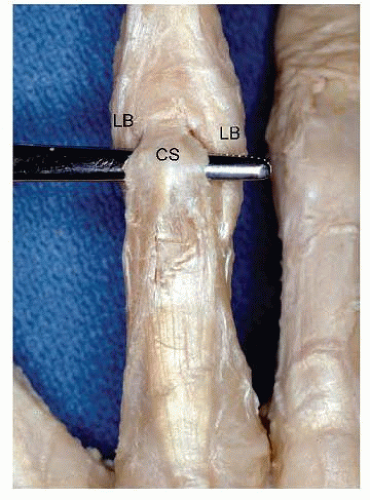

Even a low-profile dorsal plate can lead to extensor imbalance. A plate on the proximal phalanx effectively shortens and tightens the central slip tendon, leading to limited proximal interphalangeal flexion (FIG 1).

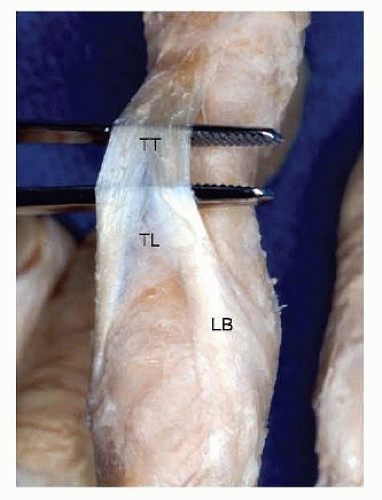

There is even less room to place a dorsal plate under the triangular ligament and terminal tendon over the middle phalanx (FIG 2).

PATHOGENESIS

Because the fingers project from the hand, they are subject to bending and twisting forces in a wide variety of situations.

The fracture pattern depends on the position of the digit at the time of injury and the direction and degree of force applied.

Long spiral fractures tend to result from torsional forces.

Transverse fractures tend to occur after angular and three-point bending forces.

Fingers are also subject to direct trauma, such as a blow from a hammer, crush injury from a window or door, or a gunshot.

These injuries are often associated with skin, tendon, nerve, and artery injuries, all of which worsen the prognosis for recovery of function.

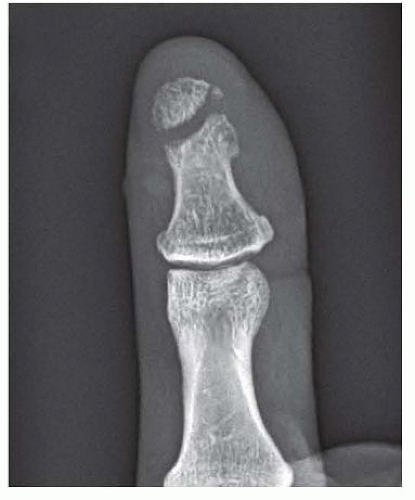

Most distal phalanx fractures are comminuted in nature and result from a crush mechanism. Significant displacement of the fragments is associated with a nail bed disruption (FIG 3).

Fractures of the proximal phalanx will generally assume a position of apex volar angulation.

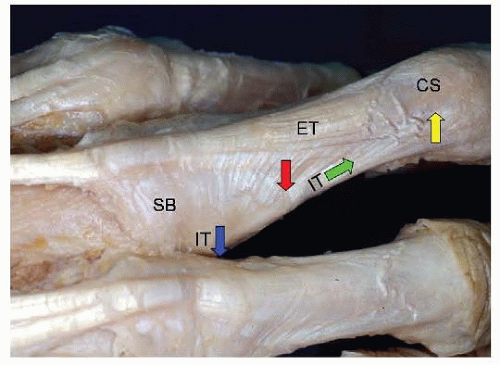

The portion of the intrinsic muscle tendons that insert on the base of the proximal phalanx pull the proximal fragment into flexion. The central slip pulls the distal fragment into extension (FIG 4).

Fractures of the middle phalanx deform less predictably but often assume an apex volar angulation due to the pull of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon on the volar base of the middle phalanx proximal fragment and the force exerted by the terminal extensor tendon on the distal fragment.

Both the extensor and flexor tendons insert on the distal phalanx at the base only. The flexor tendon insertion is more distal than the extensor tendon insertion. It is possible to have an extra-articular fracture between the two insertion sites, a so-called Seymour fracture in adults, which angulates in a dorsal apex direction.

NATURAL HISTORY

Extra-articular fractures of the phalanges typically will heal in patients who do not seek clinical treatment but often with residual deformity.

There is a linear relationship between the degree of proximal phalanx angulation and the extensor lag, which occurs because of the relative lengthening of the extensor mechanism.22

The operative correction of such deformity must be balanced with the potential for stiffness after surgical intervention as well as other potential surgical complications.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history including the date and mechanism of injury, the patient’s handedness, occupation, hobbies, and treatment rendered to date must be obtained.

As part of the history, it is important to know any previous injuries and functional limitations of the hand being evaluated.

The clinician should evaluate the cascade of the digits, looking for subtle changes in the attitude and position of the fingers. This may help to localize areas of injury.

Pain with palpation helps to localize the area of injury if there is no clear deformity of the digit. Palpation can also be useful to assess clinical fracture healing.

Phalangeal fractures can be displaced in the anteroposterior (AP) or lateral plane, rotated, shortened, or can exhibit a combination of these deformities.

Resultant hand function will depend on the specific deformity and its location along the skeleton.

The more proximal the fracture, the greater the potential for angular or rotational deformity at the fingertip.

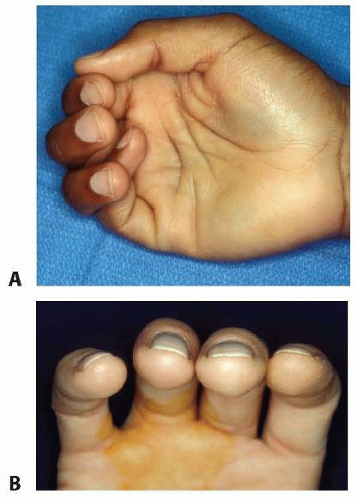

Rotational deformity affects ultimate function the greatest, especially if the rotation causes the fingers to scissor (FIG 5A).

Rotation can be evaluated by asking the patient to flex and extend the digits as a unit. The clinician should compare the relative position of the injured digit to adjacent digits on both the injured and uninjured hands.

A digital anesthetic block can facilitate the examination.

The digits should generally point toward the distal pole of the scaphoid during flexion.

It is often difficult for the patient to make a fist at the initial assessment due to pain and swelling. In these cases, comparing the plane of the nail bed of the injured finger to the adjacent nail beds can provide a valuable clue to the presence of a rotational deformity (FIG 5B).

Neurovascular status

Altered skin color and diminished turgor and capillary refill of the digit are clear indicators of vascular compromise.

Two-point discrimination can be used to assess innervation density and is an excellent method for evaluating the integrity of digital nerves in adults.

Condition of the soft tissue envelope

The skin may be visibly damaged with lacerations, degloving, or burns. Its condition will influence treatment.

A subungual hematoma is common with a distal phalanx fracture.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

PA, oblique, and lateral radiographs will provide sufficient imaging for the majority of extra-articular phalangeal fractures.

Critical evaluation may show subtle rotational malalignment if a true lateral view of either the base or the condyles of a phalanx does not match up across its corresponding joint.

Slightly oblique lateral views are useful for imaging fractures at the base of the proximal phalanx, where the overlap on a true lateral view makes evaluation difficult.

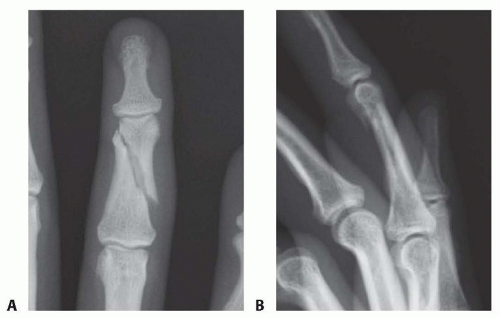

Unstable fracture patterns, such as spiral fractures with rotation and shortening, or midshaft transverse or short oblique fractures with angulation, should be recognized on the plain radiographs (FIG 6A,B).

A mobile, small fluoroscopy unit allows magnification to help characterize subtle injuries and dynamic evaluation to gauge fragment stability.

More sophisticated imaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], computed tomography [CT], ultrasound) is rarely needed to make the diagnosis of a phalangeal fracture or to guide treatment.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Although there are other causes of hand pain and deformity (eg, osteoarthritis, congenital deformity, tumor, infection), the patient history and plain radiographs should leave little doubt that the patient has a phalanx fracture.

If a fracture is not evident, all the following diagnoses should be considered:

Acute sprains (collateral ligament or volar plate injury)

Tendon injury (mallet finger, boutonnière injury, sagittal band injury, flexor tendon avulsion, or pulley rupture)

Nondisplaced fracture or bony contusion

Stenosing tenosynovitis or trigger finger

Acute infection

Benign and malignant lesions of the digits

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Many phalangeal fractures are stable and can be treated effectively by closed means.4,9,10,11 Each fracture must be addressed individually, taking into account the condition of the soft tissue envelope, the fracture characteristics, and the functional needs of the patient.

Mild (nonrotational) deformities do well with immobilization and protection while the fractures heal, but unstable or malrotated fractures benefit from surgical intervention.

Distal phalanx fractures are most commonly amenable to nonoperative treatment.

Early motion is always desirable, but it is somewhat less important with closed treatment.

Immobilization beyond 3 weeks increases stiffness and leads to worse outcomes.21

Closed treatment

Less scarring to the extensor mechanism

Less ability to move early, unless the fracture is very stable

Less ability to hold a fracture that required reduction

Internal fixation

Greater scarring of the extensors, especially with a dorsal approach and a dorsal implant

Early motion is essential

Greatest ability to hold the fracture in a stable, corrected position

If a fracture is incomplete, complete but nondisplaced, or impacted (such as the metaphysis at the base of the proximal phalanx), a short period (1 to 2 weeks) of splinting followed by buddy taping to the adjacent digit is appropriate (FIG 7).

A fracture that can be adequately reduced but is relatively unstable can occasionally be held reduced with a splint.

This has the advantage of avoiding a trip to the operating room and the possible complications of surgical fixation but requires close follow-up and serial radiographs to ensure that reduction is maintained (FIG 8).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

When considering any surgery, it is necessary to balance the potential benefits of surgery with the risks of the procedure.

The goal of surgery is to restore alignment and to stabilize the fracture to a degree sufficient to begin early motion.

Any phalangeal fracture with a significant injury to the soft tissue envelope has a worse prognosis.

Stable fixation (to the degree that it does not further compromise the soft tissues) and early motion assume a greater importance in phalangeal fractures with associated soft tissue injuries.

Patients with open fractures are treated with the appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy.20

Once the decision is made to surgically intervene, the surgeon must decide which mode of fixation will best suit the fracture pattern.

This decision is often made intraoperatively and is frequently based on the ability of the fracture to be adequately reduced closed.

Fractures that are reduced closed are stabilized externally with a cast or fixator or are held with Kirschner wires placed percutaneously.

Kirschner wiring and external fixation are techniques that, when appropriately applied, will result in acceptable outcomes without potential soft tissue surgical interruption and scarring.6

Open reduction and internal fixation with plates and screws will potentially provide more stable fixation but, without early mobilization, could result in decreased range of motion.12

Overly aggressive soft tissue stripping will cause extensor tendon adhesions and bulky implants will affect extensor tendon balance and function.18

An algorithm can be used to aid in the decision-making process (FIG 9).

Methods

Percutaneous Wire Fixation

Closed reduction with percutaneous fixation can be used to treat the majority of unstable spiral fractures of the phalanges.

The technique is also suitable for transverse metaphyseal fractures, but it may be less suited for transverse diaphyseal fractures.

When the wires are inserted radial and ulnar to the extensor mechanism, percutaneous wire fixation offers the advantage

of minimal disruption of the soft tissues in general and the extensor mechanism in particular.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree