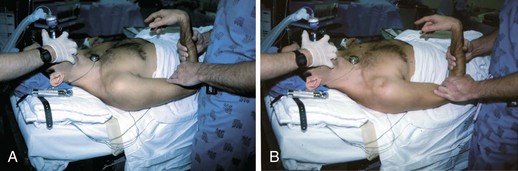

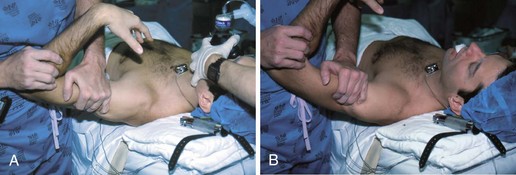

Chapter 14 One of the earliest descriptions of multidirectional instability (MDI) was offered by Neer and Foster in 1980, who described this pathologic entity as the ability to dislocate or subluxate the glenohumeral joint anteriorly, posteriorly, and inferiorly. They also reported that patients were most symptomatic during mid–range of motion while performing activities of daily living.1 MDI is described as global shoulder laxity that can be congenital, acquired, or both. It is primarily caused by the combination of a redundant inferior capsular pouch, lax ligaments about the shoulder, and weakened musculotendinous structures.2–4 Congenital laxity often occurs in multiple joints of the body in conditions such as Marfan syndrome. Acquired laxity is found in competitive athletes, specifically gymnasts and swimmers. The combination of both is found in individuals who have baseline laxity who become symptomatic after mild to moderate trauma. Diagnosis is largely by clinical examination; however, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful to evaluate the presence and extent of a traumatic component. The mainstay of treatment is nonoperative management focusing on physical therapy that involves strength and neuromuscular coordination of the rotator cuff, deltoid, and scapula.4,5 Operative management is reserved for those refractory to conservative measures. The open inferior capsular shift, as originally described by Neer and Foster,1 stabilizes the shoulder by decreasing capsular volume and has been the operative treatment of choice. With advances in arthroscopic techniques, the amount of capsular volume reduction is comparable to that with the open technique.6 The results of arthroscopic techniques have been promising, and as a result the open procedure is used less frequently but remains an option, especially in those in whom arthroscopic treatment has failed.7,8 Most patients are young adults and can have bilateral symptoms. It is important to ascertain a family history of similar complaints to evaluate for congenital causes. A psychiatric history (i.e., in voluntary or intentional dislocators) may preclude individuals from undergoing surgery.1,4 Pain is the most common presenting complaint and is generally provoked by normal daily activities. Also, a sense of instability is a frequent complaint. It is important to differentiate whether patients have pathologic hyperlaxity with pain versus laxity with pain and instability. Patients with pain and without instability have relatively poor outcomes compared with those who demonstrate instability.9 Rarely patients may report numbness, tingling, and weakness of the affected extremity. The mainstay of diagnosis is physical examination. Basic shoulder examination includes inspection for muscle atrophy, palpation for any point tenderness, and active and passive range of motion to evaluate shoulder biomechanics. As with any complete examination of the shoulder, the physician should evaluate the cervical spine. Signs of global ligamentous laxity including elbow hyperextension, ability to touch the thumb to the forearm (Fig. 14-1), and patellar subluxation are frequently observed. A positive sulcus and/or apprehension sign is common (Fig. 14-2). We also use the load and shift test to quantify both anterior and posterior laxity (Fig. 14-3).10 This is done by placing the shoulder off the edge of the table in 90 degrees of abduction and applying an anterior and posterior translational force. The result is graded as minimal translation (trace), humeral head translation to the rim (1+), translation over the rim with spontaneous reduction (2+), and dislocation (3+). The contralateral shoulder should be evaluated for laxity as well. Additional maneuvers to demonstrate increased translation include the Fukuda test and the jerk test.4 Conservative management remains the treatment of choice. Initial management should include a period of immobilization and anti-inflammatory drugs for an acute exacerbation. It is thought that MDI is caused in part by stretching of the static shoulder stabilizers. Therefore treatment should initially involve strengthening of the shoulder stabilizers including the rotator cuff muscles and deltoid. Conditioning of the upper thoracic muscles and the scapular stabilizers is also important for stability.2 A change in lifestyle to limit pain-provoking activities such as overhead work is recommended. A formal two-phase rehabilitation program including Thera-Band and lightweight exercises, focused on strengthening of the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles, has also been described.5 The primary indication for operative treatment is a failure of conservative management with persistent pain.1,2,4,11,12 Those in whom conservative management is likely to fail include patients with unilateral involvement, difficulties performing activities of daily living, and higher grades of laxity on initial examination.12 Contraindications to surgical treatment include noncompliance during a trial of conservative management, voluntary dislocation, and the presence of psychiatric abnormalities.1,13 A poor prognostic indicator, particular in athletes, is bilateral MDI requiring bilateral repair.13 The risk of limited range of motion compared with the contralateral shoulder and, conversely, persistent patholaxity should be a significant part of any preoperative discussion regarding this problem. Historically, surgical options have included thermal capsular shrinkage, glenoid osteotomy, or humeral osteotomy.4,14,15 The open inferior capsular shift, as described by Neer and Foster, has been the most commonly performed open procedure for this problem, with arthroscopic techniques now becoming increasingly common. The inferior capsular shift procedure reduces total capsular volume by releasing the inferior capsule and shifting it superiorly.1,11

Open Repair of Multidirectional Instability

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Indications and Contraindications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine