Occult Groin Injuries: Athletic Pubalgia, Sports Hernia, and Osteitis Pubis

Michael B. Gerhardt MD

John A. Brown MD

Eric Giza MD

Although most disorders of the groin in athletes are the result of injury, the broad differential diagnosis includes traumatic and atraumatic etiologies.

The groin involves the musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems, as well as a complex array of intertwining neurovascular structures. Groin pain can be the primary complaint in disorders involving any of these systems.

The most challenging cases involve presentation after weeks or months of symptoms or when pain persists despite rest and attempts at rehabilitation.

An occult groin injury is a painful, symptomatic injury isolated to the groin or pelvis region in which no clinically obvious signs are present upon exam.

Classic hernias are straightforward in that the physical exam often confirms the diagnosis and allows for early detection. Many other groin disorders can be diagnosed by clinical exam with the assistance of various imaging studies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a useful tool to rule out serious issues in the differential diagnosis.

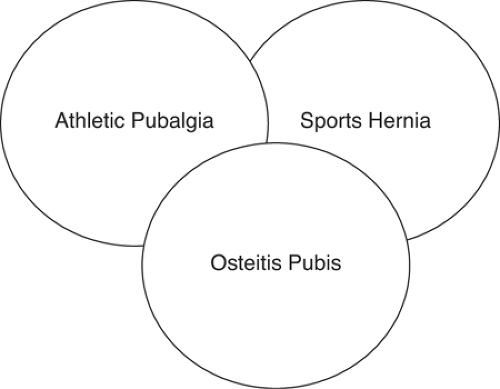

There is sometimes overlap between the three major categories of occult groin injuries—athletic pubalgia, sports hernia, and osteitis pubis.

Sports hernias may stem from an athletically induced tear during an episode of aggressive hip abduction and extension, such as occurs with lateral cutting in a football running back or the aggressive kick in soccer. The result is an incompetent abdominal wall, usually localized to the posterior inguinal canal, where the transversalis fascia resides.

The athletic pubalgia/sports hernia occurs most frequently in professional, high performance pivoting athletes.

Athletic pubalgia and sports hernias occur almost exclusively in males. Women who present with a clinical history consistent with either syndrome should be scrutinized carefully. All other sources of potential pathology and rehabilitation should be exhausted before attempting a surgical solution.

Caution should also be exercised when considering treatment of athletic pubalgia or sports hernia in nonathletes.

A significant number of patients improve with a forced period of rest. If the injury recurs upon return to the playing field, a more aggressive approach should begin.

Disorders of the groin and pelvis are a significant diagnostic challenge for the sports medicine specialist. While most disorders of the groin in athletes occur as a result of injury, the broad differential diagnosis includes traumatic and atraumatic etiologies. Several confounding clinical variables exist in this part of the body making it a difficult area to accurately assess. The groin involves a crossroads of multiple systems, including the musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems, as well as a complex array of intertwining neurovascular structures. Groin pain can be the primary chief complaint in disorders involving each of these systems. Thorough evaluation is essential in order to hone in on the correct diagnosis.

Unfortunately this is not always an easy task because the pathoanatomy of groin injuries remains poorly understood.

For example an athlete with a complaint of chronic deep groin pain may have a stress injury of the hip or pelvis, an intrarticular hip injury such as a superior acetabular labral tear (SALT lesion), a classic inguinal hernia, an upper lumbar spine disorder, or an occult groin injury. Other less common diagnostic entities such as genitourinary infections or tumors must also be kept in mind. The clinical complexity of these disorders may lead to delay in diagnosis, which is frustrating for patients and clinicians alike. Therefore it is important to have a sound general knowledge base of the various disorders causing groin pain, and to be familiar with the basic diagnostic and treatment algorithms.

For example an athlete with a complaint of chronic deep groin pain may have a stress injury of the hip or pelvis, an intrarticular hip injury such as a superior acetabular labral tear (SALT lesion), a classic inguinal hernia, an upper lumbar spine disorder, or an occult groin injury. Other less common diagnostic entities such as genitourinary infections or tumors must also be kept in mind. The clinical complexity of these disorders may lead to delay in diagnosis, which is frustrating for patients and clinicians alike. Therefore it is important to have a sound general knowledge base of the various disorders causing groin pain, and to be familiar with the basic diagnostic and treatment algorithms.

The most challenging cases involve presentation after weeks or months of symptoms or when pain persists despite rest and attempted rehabilitation. Some cases present very subtle clinical signs on physical examination. We classify these disorders as occult groin injuries, and they will be the focus of this chapter (Table 31-1). Other differential diagnoses will be listed, but will be covered in detail elsewhere in the textbook.

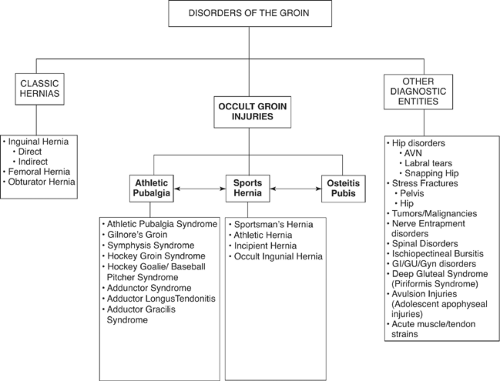

In general, we prefer to classify these disorders into three major groups: (a) occult groin injuries, and (b) classic hernias, (c) other diagnostic entities (Fig 31-1). An occult groin injury is defined as a painful, symptomatic injury isolated to the groin or pelvis region in which no clinically obvious signs are present upon exam. This is in contradistinction to a typical groin injury, such as a classic inguinal hernia in which groin pain is accompanied by hard clinical signs, such as a reducible or possibly irreducible bowel loop demonstrable by digital exam. Classic hernias are fairly straightforward in that the physical exam often confirms the diagnosis and allows for early detection and treatment. Many other groin disorders, which we classify as other diagnostic entities, can usually be diagnosed by clinical exam with the assistance of various imaging studies, e.g., a soft tissue tumor or an avascular necrosis of the hip.

At this point, we do not have a well accepted classification system for occult groin injuries, and the published nomenclature is confusing and conflicting. We prefer to consider three major categories of occult groin injuries: (a) Athletic Pubalgia, (b) Sports Hernia, and (c) Osteitis Pubis. It is sometimes impossible to separate these clinical entities, as overlap exists between the three groups (Fig 31-2). However, this classification system is useful as a framework for clinical evaluation and may help guide appropriate clinical management.

Athletic pubalgia and sports hernia are debilitating groin pain syndromes that have become major focal points in the diagnosis and treatment of the professional athlete. The concept of a debilitating focal groin injury was first described by Gilmore in 1980 as a “groin disruption” (1,2). To date there has been no real consensus on the classification of the syndromes. A variety of terms has been used to describe groin pain syndromes, including Gilmore’s groin, symphysis syndrome, hockey groin syndrome, adductor gracilis syndrome, occult inguinal hernia, sportsman’s hernia, and incipient hernia (2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9) (Table 31-1).

From a conceptual basis, athletic pubalgia is based on a biomechanical model, and sports hernia is best considered from an anatomical perspective. Both syndromes are associated with a significant loss of playing time and can be career ending. However, current treatment strategies can facilitate return to an elite level of play (2,4,5,6,7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16).

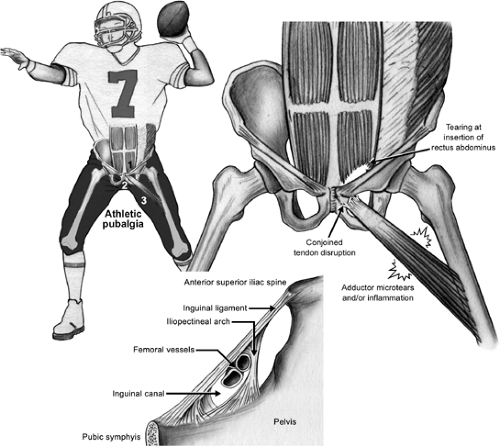

Athletic pubalgia is defined as an injury to the rectus abdominis insertion on the pubic symphysis, often accompanied by injury to the conjoined tendon insertion and the adductor longus attachment to the pelvis (7) (Fig 31-3). We believe the hallmark feature of this disorder is subtle pelvic instability. The sports hernia is defined as an injury of the transversalis fascia leading eventually to incompetency of the posterior inguinal wall (11,15,17) (Fig 31-4).

Table 31-1 Common Features of Occult Groin Injuries | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anatomy

The pathoanatomy of athletic pubalgia and sports hernia is complex. The zone of injury includes the medial extent of the inguinal canal with the transversalis fascia posterior, the tendinous rectus abdominis and conjoined tendon anterior, and the bony pubic symphysis medial. The adductor tendons and their attachment along the anterior pelvis define the distal extent of the zone of injury (2,7). The various nerves of the inguinal region are involved commonly, which may explain the typical cutaneous pain distribution to the scrotum (ilioinguinal nerve), ipsilateral and contralateral inguinal area (genitofemoral nerve), and medial thigh (obturator nerve) (18). Fon (17) describes the “sportsman’s hernia” and proposes the cause as an incipient hernia based on the findings of a posterior bulge found in 80% to 85% of the operations. He considers this analogous to a classic inguinal hernia, where the absence of striated muscle at the posterior inguinal wall and the passage of the spermatic cord predispose the abdominal wall to weakness. In the “sportsman’s hernia” an anatomically thin transversalis fascia forms this part of the posterior wall, and is prone to injury. Similarly, Joesting (14) defines the “sportsman’s hernia” as an actual tear in the transversalis fascia in the posterior inguinal wall. The tear is located between the internal inguinal ring and the pubic tubercle, typically 3-5cm in length. Lynch and Renstrom (19) also localize the pathology to the posterior inguinal wall.

Susmallian (16) describes the entity of “sportsman’s hernia” as a result of a tear of the structures around the internal

inguinal ring and the subsequent progressive weakness of the posterior wall. Kluin et al. (15) also define the term sports hernia as a weakness of the posterior inguinal wall resulting in an occult medial hernia. Genitsaris et al. (11) echoed this sentiment and under endoscopic visualization defined a defect in the posterior wall in Hesselbach’s triangle without forming a true hernia. Srinivasan and Schuricht (9) state the cause, in general, to be incompetent abdominal wall musculature. In his series, he subjectively noted the presence of an occult hernia in all cases. In a thorough review of the literature, Mora and Byrd (8) define the cause as a nonpalpable, small hernia with microscopic tearing of the internal oblique muscle attachments. Leblanc and Leblanc (20) state that the entity is a spectrum of injuries, principally involving the conjoined tendon, inguinal ligament, transversalis fascia, internal oblique muscle, and external oblique aponeurosis.

inguinal ring and the subsequent progressive weakness of the posterior wall. Kluin et al. (15) also define the term sports hernia as a weakness of the posterior inguinal wall resulting in an occult medial hernia. Genitsaris et al. (11) echoed this sentiment and under endoscopic visualization defined a defect in the posterior wall in Hesselbach’s triangle without forming a true hernia. Srinivasan and Schuricht (9) state the cause, in general, to be incompetent abdominal wall musculature. In his series, he subjectively noted the presence of an occult hernia in all cases. In a thorough review of the literature, Mora and Byrd (8) define the cause as a nonpalpable, small hernia with microscopic tearing of the internal oblique muscle attachments. Leblanc and Leblanc (20) state that the entity is a spectrum of injuries, principally involving the conjoined tendon, inguinal ligament, transversalis fascia, internal oblique muscle, and external oblique aponeurosis.

Although more broadly defined, several authors describe a constellation of injuries around the groin that can also fall under the auspices of sports hernia. Macleod and Gibbon (21) define the groin pathology in terms of pain generators. They describe four general contributors to the groin pain:

Adductor or rectus abdominis musculotendinous strains or tendoperiosteal enthesopathies

Osteitis pubis

Disruption of the inguinal canal with tearing of the superficial ring and thinning of the posterior wall

Nerve entrapment of the ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and/or obturator nerve

Fig 31—4. Proposed mechanism of injury in sports hernia. Primarily involves injury to the transversalis fascia, resulting in eventual incompetency of posterior inguinal wall (arrow). |

Similarly, Anderson (3) describes three possible sources of pain:

Abnormalities at the insertion of the rectus abdominis muscle

Avulsion of part of the internal oblique muscle fibers at the pubic tubercle

Abnormality in the external oblique muscle and aponeurosis

Some authors focus upon the effects of soft tissue injury and the biomechanics of the pelvis, without specific focus upon a structural hernia. This is what we broadly define as athletic pubalgia. Again, this is to serve as a generic term under which several clinical syndromes can be subclassified.

“Gilmore’s groin” is an entity that falls under the athletic pubalgia category. Gilmore describes variability in the intraoperative findings, but the main features include a torn external oblique aponeurosis, tearing of the conjoined tendon and avulsion from the pubic tubercle, and a dehiscence between the conjoined tendon and inguinal ligament. He reports no evidence of an actual hernia (1,2,6).

Martens et al. (22), in 1987, were the first to actually describe the concept of associated abdominal muscle and adductor injuries, as they described a specific entity composed of adductor tendinitis and musculus rectus abdominis tendonopathy. Subsequent articles introduced the term pubalgia, later to be amended to the term athletic pubalgia, upon which we base our current classification system (23). These are thought to involve microscopic tears or avulsions of the internal oblique muscle in the area commonly referred to as the conjoined tendon.

Meyers et al. (7,24) refined this definition of athletic pubalgia as injury to the rectus abdominis tendinous insertion onto the pubic symphysis with associated adductor longus related pain. They emphasize that no true hernia is present. In general, Meyers defined the injury localized to the flexion-adduction apparatus of the lower abdomen and hip, and theorized that pelvic instability secondarily occurs as a result of imbalance between the rectus and adductor muscles. Other authors agree, as evidenced by Biedert’s claim (5) that pelvic instability plays a major role in the etiology of occult groin injuries. He uses the phrase “symphysis syndrome” as a means to describe the combination of weak groin, abnormalities of the rectus abdominis at its small attachment area on the pubis, and chronic adductor pain from overuse. In his proposed model, the symphysis pubis represents the center of the different local or referred pains.

The end result of these injuries is an imbalance of the pelvic anterior stabilizing musculature, with the strong adductors overpowering the torn rectus muscles anteriorly, allowing for subtle anterior tilt of the pelvis (7). This anterior tilt leads to further abnormalities in the biokinetic chain, which ultimately causes more pain around the anterior groin, resulting in the athlete’s inability to compete at a high level.

The end result of these injuries is an imbalance of the pelvic anterior stabilizing musculature, with the strong adductors overpowering the torn rectus muscles anteriorly, allowing for subtle anterior tilt of the pelvis (7). This anterior tilt leads to further abnormalities in the biokinetic chain, which ultimately causes more pain around the anterior groin, resulting in the athlete’s inability to compete at a high level.

Holmich (25) focuses on the adductor component of the groin pain and correlates the pathophysiology with the poor blood supply at the tendon/bone interface combined with local muscular imbalance. A traumatic event or multiple microtraumas result in injury and pain in the adductor region, which is richly innervated with nociceptive fibers. Ashby (4) localizes the origin of pain to be at the medial insertion of the inguinal ligament onto the pubic symphysis; essentially an enthesopathy of the inguinal ligament.

Athletic pubalgia and sports hernia have also been described in terms of sport specific syndromes. Meyers et al. (24) describe the Hockey goalie/Baseball pitcher syndrome in which there is a localized infolding of the adductor muscle fibers between the torn fibers of the epimysium. Pain is related to the muscle entrapment that occurs. Leblanc and Leblanc (20) describe an associated entity, a subset of sports hernia, called Hockey player’s syndrome or slap shot gut. Anatomically, this may represent a tear in the external oblique aponeurosis associated with inguinal nerve entrapment. Irshad et al. (26) describe the “hockey groin syndrome.” All patients were reported to have tearing of the external oblique aponeurosis with branches of the ilioinguinal nerve emanating from the tear. He considers the entrapment of the nerve as the causative agent in the persistent pain.

A potential source of pain in these syndromes includes the cutaneous nerves that pass through the inguinal region. Akita et al. (18) performed a study in which they examined the cutaneous branches of the inguinal region in 54 halves of 27 male adult cadavers. The ilioinguinal nerve and cutaneous branches were present in 49 of 54 and genitofemoral cutaneous branches were present in 19 of 54. The cutaneous branches of the ilioinguinal nerve wind around the spermatic cord and also are distributed to the skin of the dorsal surface of the scrotum. The ilioinguinal nerve and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve probably play important roles in chronic pain associated with occult groin injuries. Pain resolution after “sports herniorraphies” may indeed be due to nerve decompression during the surgical procedure.

Biomechanics

The biomechanics of the pelvis are not completely understood. Sports hernias may stem from an athletically induced tear during an episode of aggressive hip abduction and extension, such as occurs with lateral cutting in a football running back or the aggressive kick in soccer (9,11,15,16). The results are an incompetent abdominal wall, usually localized to the posterior inguinal canal, where the transversalis fascia resides. This theory does not address the adductor symptoms that frequently accompany inguinal pain.

Pelvic pathomechanics can be a useful conceptual basis of athletic pubalgia. Proponents consider the initial injury event, the subsequent propagation of pain, the eventual chronicity, and the final disability as a continuum related to changes in the biomechanics of the pelvis, localized to the region of the pubic symphysis (2,5,7,22,23,24). The initial insult occurs at the tendinous attachments that stabilize the pelvis.

With this theory, the pubic symphysis is considered a single large joint. Along the superior edge of the symphysis are the attachments of the rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. Along the inferior edge are the attachments for the adductor group, namely the adductor longus, pectineus, and gracilis. The theoretical mechanism of injury seems to be an overuse syndrome due to repetitive hip hyperextension and truncal rotational movements leading to wear and tear and eventual failure (acute or acute on chronic) of the abdominal musculotendinous attachments to the pelvis (6).

More specifically, hip adduction/abduction and flexion/extension with the resultant pelvic motion produces a shearing force across the pubic symphysis leading to stress on the inguinal wall musculature. In combination, pull from the adductor musculature against a fixed lower extremity causes shear forces across the hemipelvis (3). Once the injury has progressed to the point of pelvic microinstability, the rectus attachment is incompetent and allows the pelvis to tilt anteriorly. Theoretically, the anterior tilt and the unopposed adductor muscle group results in increased pressure in the adductor compartment, possibly creating an “adductor compartment syndrome” with resulting adductor pain (7). With time, the failure of the support mechanism on one side of the pubis creates an overuse type scenario for the contralateral rectus and adductor group, resulting in the same problem on the opposite side. It is emphasized that the problem is not related to a classical inguinal hernia mechanism.

Clinical Evaluation

History

The athletic pubalgia/sports hernia occurs most frequently in professional, high performance pivoting athletes. In the United States, NFL football players and NHL hockey players are most commonly affected (7,24), while in Europe professional soccer players are at highest risk (2,11). It may occur in recreational athletes; however, treatment of this group is much less predictable (7,14).

These syndromes occur almost exclusively in males (7,15). Women who present with a clinical history consistent with athletic pubalgia or sports hernia should be scrutinized carefully. Routine laparoscopic evaluation is recommended for females being worked up for an occult groin injury (7).

In one study, 17 of 20 females, who were suspected of having athletic pubalgia underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, and all but one of these women were found to have another cause for the pain, with endometriosis being the most common diagnosis (7).

In one study, 17 of 20 females, who were suspected of having athletic pubalgia underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, and all but one of these women were found to have another cause for the pain, with endometriosis being the most common diagnosis (7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree