PREVALENCE OF OBSESSIONS AND COMPULSIONS

Obsessions and compulsions occur as normal phenomena, differentiated from their OCD counterparts by the distress or disruption they cause. Normal obsessions occur in 80–88 per cent of individuals, and the content of normal and abnormal obsessions are similar (Rachman & de Silva, 1978; Salkovskis & Harrison, 1984). Estimates of the prevalence rates of OCD vary. The Epidemiological Catchment Area survey indicated that the lifetime prevalence of OCD was 2.5 per cent, and the six-month prevalence rate was 1.6 per cent, making it the fourth most common psychiatric disorder in the USA (Karno, Golding, Sorenson & Burnam, 1988).

COGNITIVE MODELS OF OCD

A wide range of concepts have been evoked in the development of cognitive theoretical models of OCD. Different perspectives have emphasised the role of perfectionistic beliefs (McFall & Wollersheim, 1979), inflated responsibility (Rachman, 1976; Salkovskis, 1985), cognitive deficits or abnormalities in decision making (Reed, 1985; Persons & Foa, 1984; Sher, Mann & Frost, 1984), thought action-fusion (Rachman, 1993) and meta-cognitive beliefs (Clark & Purdon, 1993; Wells & Matthews, 1994).

A diversity in theoretical concepts, lack of a generally agreed framework, and limited research on cognitive dimensions of obsessions contribute to the underdevelopment of cognitive models of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients presenting with OCD continue to present a considerable challenge to the therapist. Behavioural treatment consisting of exposure to obsessional stimuli and prevention of ritualistic behaviour (Meyer, 1966) shows consistent positive results (e.g. Foa, Kozak, Steketee & McCarthy, 1992; Marks, Hodgson & Rachman, 1975). The addition of cognitive therapy has yet to show that it consistently improves outcome over and above exposure and response prevention alone.

The Salkovskis model

A comprehensive cognitive analysis of OCD, and one based within Beck’s cognitive theory, has been presented by Salkovskis (1985). Salkovskis’s original formulation integrated important cognitive and behavioural concepts in the cognitive formulation of obsessional problems. It combined features of earlier models such as the concept of inflated responsibility (e.g. Rachman, 1976), beliefs about thought and action (e.g. McFall & Wollersheim, 1979) with behavioural principles. One of its most influential contributions is the delineation of the importance of appraisal of intrusions as the major source of distress, rather than the content of the intrusion itself, and an emphasis on the concept of such appraisals relating to the concept of responsibility. More recently, Salkovskis (1989) has elaborated further the role of appraised responsibility in obsessional problems. According to his model, obsessional patients interpret the occurrence of intrusive cognitions as an indication that they may be responsible for harm unless they take action to prevent it. The appraisal of the significance of intrusions is determined by underlying beliefs such as: ‘Having a thought about an action is like performing the action; not neutralising when an intrusion has occurred is similar or equivalent to seeking or wanting the harm involved in that intrusion to happen; one should (and can) exercise control over one’s thoughts.’ Negative appraisals of intrusions occur as negative automatic thoughts and are amplified by states of depressed mood because of the increased accessibility of negative schemata. Once negative appraisals of responsibility occur, the second process characteristic of obsessional problems is the initiation of neutralising responses, which may be internal (e.g. trying to think positive thoughts) or external (e.g. compulsive hand-washing in response to thoughts about contracting disease). Neutralising responses reduce responsibility and discomfort and are maintained by this association, and the recurrence of intrusions becomes more likely because responses to them result in such cognitions acquiring greater salience. The mechanism by which intrusions acquire ‘greater salience’ is not elaborated in detail. However, one possibility is that attempts to suppress unwanted thoughts leads to a rebound of unwanted thought (e.g. Wegner, Schneider, Carter & White, 1987).

In this model, overt or covert neutralising responses are motivated by beliefs concerning responsibility. Salkovskis, Richards and Forrester (1995) define neutralising as: ‘voluntarily initiated and conducted activity which is intended to have the effect of reducing the perceived level of responsibility’ (p. 285).

The Salkovskis (1985) model implies that cognitive therapy should concentrate on modifying automatic thoughts and beliefs concerning responsibility for harm. However, other theorists argue that this approach overemphasises the role of responsibility (Clark & Purdon, 1993), and meta-cognitive beliefs concerning the need to control thoughts should be given careful consideration in treatment. Wells & Matthews (1994, 1997) proposed that meta-cognitive beliefs concerning the danger and power of intrusive thoughts, and the attentional strategies used by obsessionals, are relevant in understanding the disorder. They view responsibility appraisals as emergent properties of meta-cognitive processing, and as markers for dysfunctional beliefs about the dangers and influence of thoughts which are more central to OCD.

The Wells and Matthews meta-cognitive model

Wells and Matthews (1994) present a prototypical model of OCD mapped on a detailed cognitive processing framework of vulnerability to emotional disorder. They suggest that intrusions activate beliefs concerning the significance of the intrusion. These beliefs not only consist of information about intrusions but also consist of knowledge about behavioural responses. Beliefs about behaviour in OCD have received little attention in theoretical accounts. Greater consideration of such beliefs may facilitate conceptualisation of obsessive-compulsive problems.

In a meta-cognitive framework, beliefs about intrusions are relevant in understanding OCD. Rachman (1993) has introduced a useful new concept of ‘thought–action fusion’ (TAF) which represents meta-cognitive beliefs equating thoughts with actions (e.g. having a thought about harming my children means I am going to harm them). Meta-cognitive beliefs concern the consequences of thoughts (e.g. thoughts can cause actions/events) and the meaning of thoughts for past actions/events (e.g. if I think I have done something bad I probably have done it). Belief in TAF is likely to motivate particular behavioural responses such as trying to control actions or thinking. For example, if an individual believes that having a negative thought means that he/she has done something negative, the individual may engage mental or behavioural checking in an attempt to invalidate the intrusion. For instance a patient had the thought that she had stabbed her children and felt compelled to check her children’s bedroom to reassure herself that she had not done so. Implicit in this response was the belief: ‘Having this thought means I have probably carried out the action depicted in the thought.’ In many cases the obsessional patient intellectually refutes such a belief. However, under triggering conditions, doubt concerning the invalidity of thoughts is likely to increase. At a superordinate meta-cognitive level one might suppose that these examples reflect the existence of a general-purpose belief that intrusive thoughts reflect reality. More specifically, some obsessional patients appear to be operating with a mental-model of experience that blurs important boundaries between internal (cognitive) and external events.

While some behavioural responses, such as covert neutralising or controlling one’s mind, may be intended to prevent negative outcomes associated with intrusion, other behaviours are intended to relieve worry and discomfort. In the previous example the individual checked her children in order to terminate her rumination about having harmed them (not to prevent harm). The discomfort-reducing effects of such behaviours is likely to reinforce beliefs about neutralising/checking responses. The obsessional patient is prone to believe that neutralising is beneficial and not neutralising will have negative consequences of at least leading to perpetual worry and discomfort. However, neutralising behaviours and rituals themselves can become a source of distress as they become more time-consuming and are appraised as uncontrollable and dangerous. Two recent cases illustrates the use of checking behaviours to terminate worry–rumination cycles. In one case a 27-year-old sufferer of OCD reported recurrent thoughts that she had beaten up or mutilated her children or friends, and had dumped their bodies in the dustbin. These thoughts were followed by extended periods of rumination in which she attempted to reassure herself that this was not true; however, her doubts led her to check the dustbin in order to relieve her anxiety. In another case, a 36-year-old obsessional patient presented with problems of repeated checking during driving. He would drive his route home from work several times until he felt confident that he had not accidentally collided with someone. His checking was stimulated by intrusive images of having hit someone or by the thought ‘What if I’ve knocked someone down?’. When asked what would happen if he did not check, he reported that he would not be able to ‘get it off his mind’.

In summary, it is proposed that beliefs supporting the fusion of thought and action and positive and negative beliefs about rumination and neutralising strategies are relevant in conceptualising OCD. Once an intrusion has been appraised as dangerous, the individual is compelled to select a strategy for overcoming this danger. The strategy selected is determined by beliefs held concerning different strategies. In some instances, the individual will continue to ruminate and reprocess the intrusion, in order to challenge the intrusion’s validity. This is likely to be associated with beliefs concerning the appropriateness of such a strategy. However, dwelling on the intrusion is prone to exaggerate rumination and worry, and can lead to secondary problems of fear of worry itself. Another possibility is to engage in neutralising or checking behaviours which can terminate the rumination cycle by mechanisms of distraction, activating ‘superstitious’ beliefs about safety, or by reality testing of intrusive thoughts. In this model, behavioural and cognitive neutralising and checking responses are aimed at reducing the danger associated with the initial intrusion or the danger associated with sustained rumination or worry about the intrusion. Overt neutralising can be seen as a behavioural form of rumination which itself can be subject to negative appraisal. In summary, a number of different feedback cycles may operate. With different combinations of cycles operating in different cases. The overall effect is an escalation of distress, and increasing amounts of effort and time required by combinations of negative appraisals and dysfunctional responses to them.

Attentional strategies

Apart from specification of meta-cognitive beliefs in OCD, Wells and Matthews (1994, 1997) suggest that the attentional strategies adopted by patients are likely to maintain OCD. More specifically, obsessionals are prone to focus on and monitor their thought processes, this heightened cognitive self-consciousness is likely to increase the detection of unwanted target thoughts, and it may even trigger intrusions. Wells and Mathews (1994) suggest that obsessionals have a tendency to assign priority to internally generated events rather than external events. Thus, even when sensory input confirms the execution of a behaviour, individuals focus excessive attention on fantasies concerning the consequences of not performing the action. This tendency to focus on doubts or internal fantasies reduces confidence in memory for actions/events and may contribute to checking behaviour. (Note, however, that checking is also likely to be stimulated by beliefs concerning the advantages of checking.)

A GENERAL WORKING MODEL

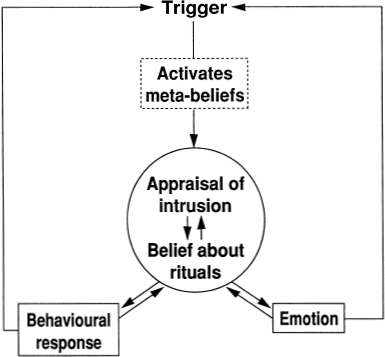

An outline general working model of relationships between beliefs, behaviours and emotion in OCD is depicted in Figure 9.0. This model is intended to be a working template for clinically representing the relationships between key variables in the maintenance of obsessions with compulsions. It is presented as a model for developing individual case conceptualisations.

Figure 9.0 A cognitive model of OCD

In this model a trigger (most often an intrusive thought or doubt, although an intrusive feeling/emotion can also act as a trigger) activates beliefs concerning the meaning of the trigger. The beliefs relevant at this level include: beliefs about the dangers and meaning of thought encompassing themes of thought–action fusion and thought–event fusion; and beliefs about the consequences of emotion/discomfort. These beliefs influence the nature of appraisals of intrusions. A further influence on appraisals of intrusion results from beliefs that the individual holds concerning rituals and behavioural responses. Two types of belief are relevant here: positive beliefs (e.g. ‘If I wash without thinking a bad thought, bad things won’t happen’; ‘If I don’t perform my ritual the feeling will never end’), and negative beliefs (e.g. ‘My rituals are out of control’; ‘My mental rituals could damage my body’). Beliefs about the dangers and advantages of available responses influence the selection and implementation of behaviours, and influence the intensity of short-term emotional reactions. However, two feedback loops operate, as depicted in Figure 9.0. Anxiety and other negative emotional reactions resulting from the appraisal of intrusions may be subject to negative interpretation; for example, anxious symptoms may be misinterpreted as a sign of loss of control or a sign of other dangers associated with intrusions. Emotional responses increase the likelihood of further intrusions, as depicted by the feedback loop back to trigger. Emotional responses are likely to lower thresholds for the detection of obsessional stimuli. Moreover, the subjective emotional state may act as a trigger in its own right, such that some individuals believe that they will be overwhelmed with negative feelings or that feelings will be unremitting unless a ritual is performed.

The behavioural responses implemented by the OCD patient maintain the problem through two feedback cycles illustrated in Figure 9.0. Behavioural responses prevent disconfirmation of belief in dysfunctional appraisals of intrusions. The non-occurrence of catastrophic actions or events resulting from intrusions is attributed to the ritual and not to the fact that the appraisal of the intrusion is not valid. The feedback cycle back to triggers represents how behavioural responses exacerbate intrusions. Three main mechanisms are involved here: First, attempts to suppress thoughts can cause an enhancement of unwanted thoughts. Second, attempts to ruminate on intrusions or mentally neutralise them can maintain preoccupation with mental events, making intrusion more likely. Third, activities such as repeated checking or cleaning can set up associations between a range of stimuli and intrusions, such that a widening array of stimuli/actions can trigger intrusions. Different overt and covert behavioural responses can be identified, these include: overt checking, rituals, ordering, repeating, washing/cleaning, thought suppression, rumination, counting, focusing, controlling one’s mind, distraction.

DEVELOPING A CASE FORMULATION

In order to translate the preliminary model depicted in Figure 9.0 into an individual case formulation, it is necessary to elicit information concerning: (1) nature of the obsessional and compulsive symptoms; (2) triggering influences; (3) appraisals of the meaning and significance of obsessions and compulsions.

Symptom profile and triggering influences

We saw in Chapter 2 that OCD symptoms can be assessed in terms of parameters such as frequency, duration and associated distress using subjective visual analogue ratings or diary measures. While these data provide information on base rates which is useful for monitoring treatment effectiveness, the data can be useful for discovering patterns in symptoms, and establishing triggers and relationships among affect, intrusive experiences and situational cues. Therapists should review with the patient a recent obsessive-compulsive episode and attempt to elicit triggers for overt and covert neutralising, checking behaviour, etc. Initially patient insight may be poor. An initial aim of treatment is to increase the patient’s level of meta-cognitive awareness so that he/she is able to identify intrusive thoughts, doubts or feelings prior to the commission of behavioural responses. This task can be initiated through a detailed review of several recent episodes, through behaviour tests involving exposure to problematic situations, and through detailed self-monitoring.

Eliciting dysfunctional appraisals

Therapists should aim to explore different categories of appraisals of intrusions, and of responses to intrusions. In assessing appraisals of intrusions, questions should be directed at eliciting dangers linked with intrusions, and the real-world validity of intrusions. The following questions and adaptations are suggested for this purpose:

Appraisals of intrusions

- When you had (intrusion) how did you feel (e.g. anxious, afraid, guilty)?

- When you felt (e.g. anxious) what thoughts went through your mind?

- Did you have any negative thoughts about the intrusion?

- What did having the thought mean to you?

- What sense do you make out of having these intrusions? Do they tell you anything? What do they tell you about your actions or about events?

- Could anything bad happen as a result of having the intrusion? What could happen?

- Does the intrusion mean something bad has happened? What is that?

- Is it normal to have thoughts like this?

- What would happen if you couldn’t get rid of these intrusions? What’s the worst that could happen?

Appraisals of behavioural responses

The present model presents a role for beliefs about behavioural responses in OCD. In developing cognitive conceptualisations of OCD it is useful to explore the appraisals and beliefs associated with the use of ritual behaviours. Some patients are fearful of giving up behaviours because of negative beliefs concerning the consequences of doing this. In other words they have positive beliefs about rituals. In some cases negative beliefs about rituals exist that contribute to distress. The occurrence of rituals in the absence of initial obsessions, suggests that the behaviour is not aimed at reducing a danger associated with a discrete intrusive thought. However, this does not necessarily mean that a danger-related appraisal is not present. In some instances of compulsive behaviour without obsessions, danger appraisals concern the emotional consequences of not engaging in the ritualised behaviour. For example, in a recent case of compulsive finger-nail cleaning, it was evident that the behaviour was triggered by subjective feelings of distress. The individual concerned believed that if she did not perform the behaviour her emotions would become ‘overwhelming’ and she would not be able to function. Furthermore, she believed that her negative feelings would become permanent. However, she also reported negative appraisals concerning loss of control of her ritual finger-nail cleaning. This negative appraisal contributed to her general level of distress, thus increasing the perceived need to engage in the ritual. Thus the patient was trapped in a vicious cycle of feeling compelled to perform the ritual to reduce distress but appraising the ritual in a way that contributed to distress. Use of the ritual behaviour to reduce the dangers associated with emotion prevented exposure to disconfirmatory experiences, such as the experience that emotion would naturally decay with time.

Examples follow of questions that are useful for eliciting appraisals associated with ritual behaviours. Note that for clinical purposes it is often necessary to elicit material by questioning the worst consequences of not engaging in a ritual behaviour, rather than only questioning about the benefits of engaging in behaviour.

- Do you do anything to prevent (catastrophe associated with intrusion) from happening? What do you do?

- Could anything bad occur if you continue to use the strategy? What is that?

- What’s the worst that could happen if you didn’t use the strategy?

- Are you bothered by (checking, neutralising, ruminating)? (If so) Why don’t you just stop?

- How much control do you have over your (checking, neutralising, rumination)?

- What’s the worst that could happen if you don’t stop it?

- How does (checking, ruminating, neutralising) help?

- Does your (checking, ruminating, neutralising) keep you safe in some way? How does that work?

- Have you tried to stop?

- Is there a reason for not trying to stop?

- What happens to your feelings/thoughts when you are prevented from (neutralising, etc.)?

CONCEPTUALISATION INTERVIEW: A CASE EXAMPLE

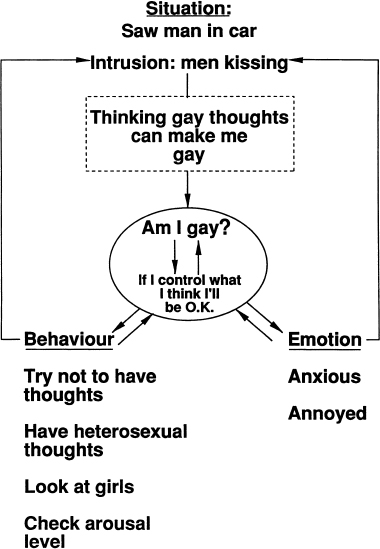

At this juncture it will be useful to illustrate how the basic questions presented previously are combined to elicit information for building an idiosyncratic case conceptualisation based on the model. An idiosyncratic conceptualisation is presented in Figure 9.1.

The person interviewed was a 24-year-old man with a seven-year history of OCD. His main presenting problem was the experience of repetitive intrusive thoughts and images of a homosexual nature. More specifically, he reported intrusive images of two men kissing, and whenever he noticed himself looking at a man in the street he had the intrusive doubt ‘Do I find him attractive?’. These obsessions were accompanied by a range of selfreassurance strategies, neutralising strategies, and danger-limitation responses which became clear in the interview. The following abstract illustrates the elicitation of relevant material for constructing the conceptualisation presented in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 An idiosyncratic OCD case conceptualisation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree