CHAPTER 37 Nonosseous Spinal Tumors

INTRODUCTION

Only 15% of primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors are intraspinal.1 Nonosseous spinal tumors represent a collection of pathologic entities that are difficult to differentiate from each other based on clinical findings, and more importantly are sometimes difficult to distinguish from the much more common degenerative spinal disorders. Obviously, it is important to make this distinction when evaluating patients with spinal disorders, but the ready availability of high-resolution imaging has removed the majority of suspense in making these distinctions. However, a basic understanding of the pathophysiology of spinal tumors and the key elements in the history and physical examination that help differentiate them from degenerative spinal pathologies are essential to avoid delayed or erroneous diagnosis. A suspicion of a spinal tumor may lead to earlier spinal imaging, as well as more comprehensive imaging to include portions of the spine that would otherwise not be imaged. We cannot overemphasize the importance of evaluating the history and physical examination for inconsistencies and ‘red flags’ such as a history of systemic malignancy, family history of syndromic tumors (neurofibromatosis, von Hippel – Lindau), nocturnal or recumbent pain, unusual radicular or medullary (burning, dysesthetic, nonradicular, as with a syrinx) symptoms, spasticity or other pathologic reflexes, bowel/bladder/sexual involvement. One additional difficulty in differentiating spinal tumor types from each other is that because the majority of symptoms are from compression, symptomatology in general is more related to the level of the lesion that the identity of the lesion itself. However, as will be discussed in subsequent sections, there is a regional predilection for each tumor and some lesions have distinct clinical findings secondary to associated pathologic changes (i.e. a syrinx associated with an intramedullary tumor). Our intention with this chapter is to give a concise and organized summary of nonosseous spinal tumors in addition to suggesting a rational approach to differentiating these lesions from more common spinal pathologies.

Nonosseous spinal tumors can be generally separated in three general categories: (1) extradural (55–60%), arising in the epidural space or in vertebral bodies; (2) intradural/extramedullary (30–40%); and (3) intramedullary (5–10%).2 These distinct categories are somewhat oversimplified as some tumors can span more than one compartment. Additionally, while metastasis can be found in all groups, the vast majority are extradural.

EXTRADURAL TUMORS

Tumors arising in and from bone will be discussed in other sections of this book. The majority of extradural tumors, with or without bone involvement, are metastatic in nature. Lymphomas are somewhat unique in that they can present with only epidural involvement and little or no bone involvement (Fig. 37.1).3 Schwannomas and meningiomas can be wholly or partially extradural but these tumors will be covered in the section on intradural/extramedullary tumors. Other more unusual causes of extradural spinal cord compressions include benign angiolipomas.4 Epidural lipomatosis is an infrequent cause of epidural spinal cord compression associated with chronic steroid use.5 Finally, epidural abscess can present as a mass lesion with or without associated discitis and osteomyelitis (Fig. 37.2).

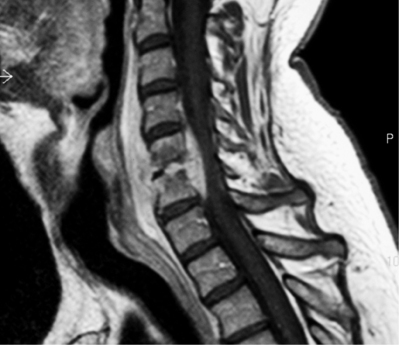

Fig. 37.1 Sagittal T1 MRI with contrast showing compression of the thecal sac from extradural lymphoma.

INTRADURAL/EXTRAMEDULLARY TUMORS

The clinical features of intradural/extramedullary tumors generally reflect the slow-growing nature of these tumors and are more dependent on location within the spinal axis rather than specific pathology. Upper cervical and foramen magnum lesions often arise ventrally and can present with long tract signs as well as headaches and a syndrome of distal arm weakness, hand clumsiness, and intrinsic hand muscle wasting.6,7 Local/regional pain is a common initial symptom in both nerve sheath tumors and meningiomas. Because of the origin of nerve sheath tumors, they are more likely to also have radicular symptoms.8,9 These regional/radicular symptoms generally precede compressive cord symptoms. Hand and arm weakness as well as local and/or radicular sensory disturbances, and long tract signs, are common in mid and lower cervical lesions. Lateralizing asymmetry including Brown-Séquard type of findings (ipsilateral motor and proprioceptive and contralateral sensory derangement) can also be seen.10 Other less common presenting syndromes include hydrocephalus (thought to be related to increased cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] protein which alters absorption)11 and subarachnoid hemorrhage from schwannomas.12

Lesions in the cauda equina present very commonly with back and radiating leg pain except for lipomas. Early sphincter disturbances are more common in lesions at the conus or cauda equine.13

Nerve sheath tumors

Nerve sheath tumors consist of neurofibromas and schwannomas which have a common cell of origin, the myelin-producing Schwann cell. The distinction is ultimately histopathological, as neurofibromas expand the involved nerve in a fusiform fashion with nerve fibers intermingled in the substance of the tumor. Schwannomas arise in a more eccentric, globoid fashion with a more discrete attachment to the nerve. Nerve sheath tumors account for approximately 40% of intradural/extramedullary tumors in adults, with an annual incidence of 0.3–0.4 per 100 000.9 Men and women are affected equally, and generally within the fourth to sixth decades of life. Most solitary schwannomas are nonsyndromic and are distributed proportionally throughout the spine. Multiple nerve sheath tumors are seen in patients with neurofibromatosis, with neurofibromas predominating in NF1 and schwannomas predominating in NF2. Multiple schwannomas can occur in patients without a recognized genetic predisposition. Approximately 2.5% of nerve sheath tumors show malignant degeneration,9 with more than half associated with neurofibromatosis. Malignant nerve sheath tumors have a very poor prognosis.

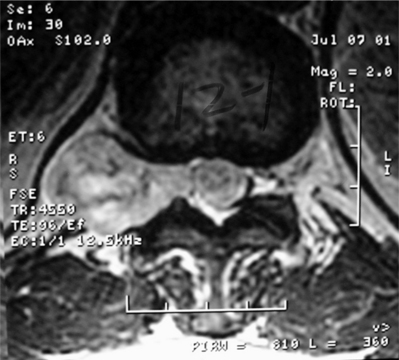

Schwanommas with extradural extension (dumbbell schwannomas) often show a smooth expansion of the bony foramen (Fig. 37.3). Extramedullary tumors by definition displace the cord by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and myelogram. MRI has become the imaging modality of choice for spinal lesions. The MRI appearance of schwannomas can help differentiate them from meningiomas in that schwannomas are somewhat hypointense to spinal cord on T1 and hyperintense on T2 (Fig. 37.4).2 Enhancement tends to be heterogeneous and a predominantly peripheral pattern of enhancement is not uncommon. This may be due to cystic, hemorrhagic, or necrotic changes. Nerve sheath tumors that are predominantly intradural are usually amenable to complete resection and have a low recurrence rate with complete resection.10 The nerve fibers of origin of the tumor often have to be sectioned to allow complete resection. This rarely results in significant neurologic deficit even at the cervical or lumbar level, as adjacent roots may have assumed some of the neurologic function.8,14–16 However, intraoperative nerve monitoring/stimulation helps guide intraoperative decision-making.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree