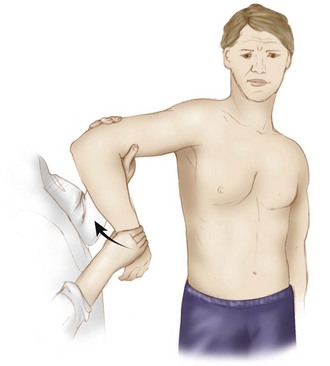

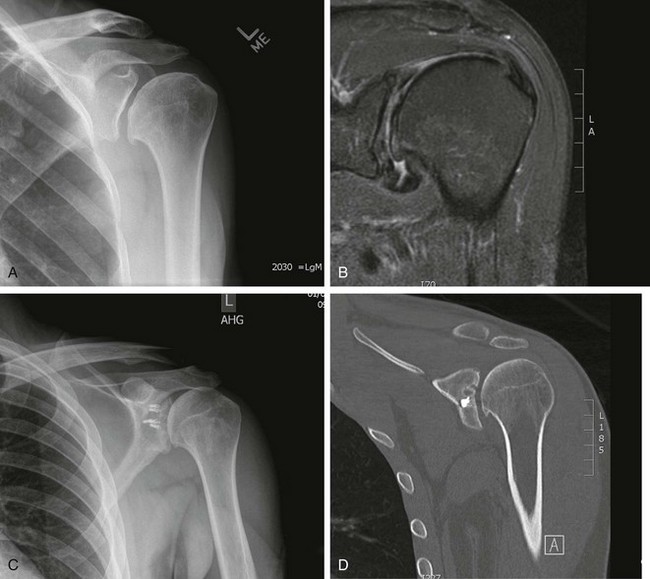

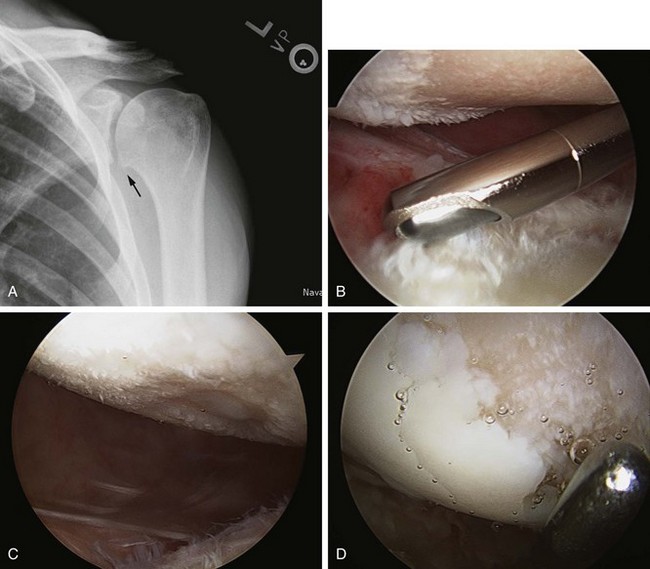

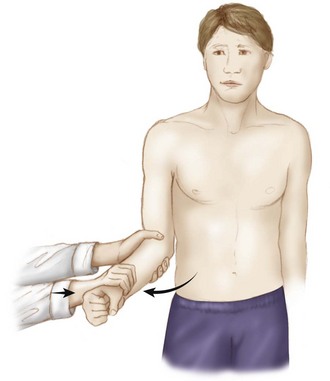

Chapter 36 Glenohumeral arthritis and chondrolysis in the young, active patient population represent difficult clinical scenarios for even the most experienced of orthopedic surgeons. Even the diagnosis of symptomatic cartilage lesions can be challenging, as these patients often have multiple injuries and varying pain complaints making it difficult to determine which pathology is the primary generator of symptoms. A thorough understanding of shoulder pathoanatomy is critical for appropriate clinical decision making to provide effective treatment. Overall, the diagnosis of a symptomatic chondral injury is one of exclusion.1 Whereas isolated articular cartilage lesions of the glenohumeral joint are rare, these lesions can become extremely painful and functionally limiting. Nonoperative treatment includes activity modification, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and intra-articular injections of corticosteroids and/or hyaluronic acid solutions (off-label usage). Unfortunately, their effects are usually temporary at best. Surgical options range from simple arthroscopic treatment to arthroplasty. Total shoulder arthroplasty remains the gold standard for glenohumeral arthritis treatment and is successful at relieving pain and restoring function. Concerns regarding component loosening, ability to perform high-level athletic activity, and the potential need for early revision surgery make this a less attractive option in a younger patient population. Other surgical treatment options range from palliative arthroscopic debridement and capsular release (capsulectomy) to reparative (microfracture), restorative (osteochondral autograft or allograft and autologous chondrocyte implantation [ACI]), and reconstructive surgical techniques (biologic resurfacing). With recent advances in diagnostic modalities, surgical techniques, and biologic implants, the treatment algorithm for these difficult patients is evolving, and no single nonarthroplasty option has been identified as the gold standard. The purposes of this chapter are to provide an overview of the typical patient with glenohumeral arthritis or chondrolysis, to discuss patient evaluation and appropriate clinical decision making, and finally to describe the various nonarthroplasty surgical treatment options for these challenging clinical situations. As previously described, articular cartilage lesions of the shoulder are often incidental findings discovered during preoperative imaging studies or during diagnostic arthroscopy. Treating asymptomatic lesions can be detrimental because the true cause of symptoms may be ignored or missed, and the treatment itself may cause further damage to the chondral surface. It is critical to determine if glenoid or humeral head articular cartilage lesions are truly symptomatic, and the diagnostic approach begins with a thorough patient history. In patients with multiple shoulder pathologies and those who have undergone prior operations, it is even more challenging to determine if current articular defects were actually responsible for their previous, preoperative symptoms. In addition, patients with previous shoulder surgery and intra-articular pain pump placement are at risk for the development of postsurgical glenohumeral chondrolysis.2–7 During the initial office visit, the clinician should inquire about the following: • Tenderness to palpation—rule out subacromial bursitis – Decreased forward flexion caused by an inferior humeral head spur. – Decreased external rotation caused by a flattened humeral head. – Decreased external rotation at the side (ERs) can indicate anterior capsular contracture, including the rotator interval, the superior and middle glenohumeral ligament, and the coracohumeral ligament (Fig. 36-1). Figure 36-1 Examination of external rotation at the side that is contracted, with tight external rotation at the side. – Decreased abduction and external rotation (ABER) can indicate anterior and anteroinferior capsule contracture. – Decreased abduction and internal rotation (ABIR) can indicate posterior and posteroinferior capsule contracture (Fig. 36-2). – Decreased abduction (ABD) can indicate inferior capsule contracture and possible involvement of the superior capsule or superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) region. • Crepitus with ROM—painless versus painful • Clicking, catching, or locking with ROM Imaging studies are routinely used in the evaluation of glenohumeral chondral lesions and typically include radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA), and computed tomography (CT). Despite advances in imaging techniques, glenohumeral articular surface defects may not be easily seen on plain radiographs or with other advanced imaging modalities, and glenohumeral arthroscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Imaging is, however, extremely helpful not only for diagnosis, but especially for preoperative planning. Specific planning considerations include the chondral anatomy of the shoulder joint. Normally the humeral head cartilage is thickest in the center (1.2 to 1.3 mm thick) and thinner at the periphery (less than 1.0 mm thick).8 In contrast, the glenoid cartilage is thickest along the periphery, tapering centrally to the bare area where it is completely devoid of cartilage. Knowledge of normal anatomy in conjunction with information supplied by imaging studies helps determine the significance of lesions based on their location along the humeral head and/or glenoid surface. Every patient should undergo a standard radiographic series of the shoulder including an anteroposterior (AP) view, a true AP view (especially important to assess subtle joint space changes), a scapular-Y view, and an axillary lateral view. These views evaluate the joint space for glenohumeral arthritis and may show overt bony abnormalities. Other specific radiographs include the Stryker notch view to evaluate Hill-Sachs lesions and the Garth (apical oblique) view to evaluate glenoid bone loss4 (Fig. 36-3). The earliest signs of glenohumeral wear are usually in the posteroinferior quadrant of the shoulder and may demonstrate joint space narrowing or subtle posterior joint subluxation (Fig. 36-4). MRI and MRA are the imaging modalities of choice for the evaluation of glenohumeral chondral surface lesions. In addition to evaluating the articular surface, MRI and MRA can detect subchondral bone changes and concomitant soft tissue ligamentous, labral, and rotator cuff pathology.9,10 All sequences should be analyzed, though the T2-weighted image (with and without fat suppression) and the T1-weighted fat-suppressed three-dimensional spoiled gradient-echo technique are most helpful.

Nonarthroplasty Options for Glenohumeral Arthritis and Chondrolysis

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Radiographs

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Arthrography

Indications and Contraindications

Relative Contraindications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nonarthroplasty Options for Glenohumeral Arthritis and Chondrolysis