Neurological trauma

Dennis W. Klima

Introduction

A key component of geriatric rehabilitation includes the management of older patients who have sustained neurological trauma to the brain or spinal cord. Therapists must consider the impact of these injuries, along with adjacent neural changes that occur during the aging process. Management of older patients with both spinal cord (SCI) and traumatic brain injuries (TBI) requires the integration of musculoskeletal, neuromuscular and cognitive interventions to enable them to effectively progress towards established goals.

A thorough history must first be obtained from the patient or family to ascertain the previous level of function. A systems review will further corroborate any changes in physical status, affect and cognition that have occurred following the sustained injury. Selected tests and measures typically combine traditional examination activities along with instruments specifically geared towards patients with TBI or SCI. A summative evaluation will then be formulated, along with an appropriate rehabilitation diagnosis and prognosis. With both patient populations of individuals who have sustained a TBI or SCI, the rehabilitation diagnosis is influenced by a multitude of mitigating factors such as age-related changes in organ systems, as well as injury complications such as heterotopic ossificans and autonomic nervous system dysfunction.

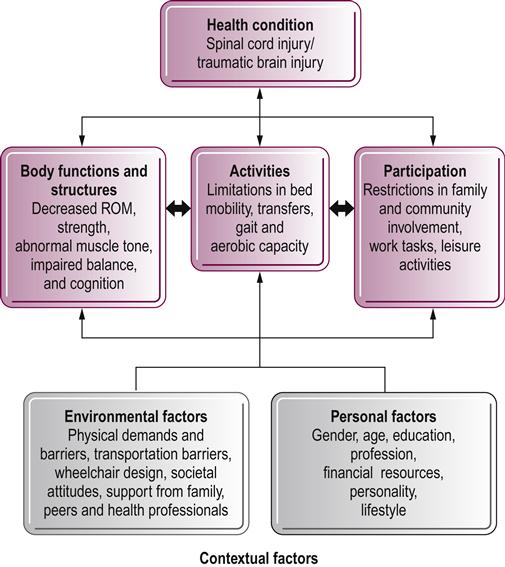

The International Classification of Function, Disability and Health model (ICF) illustrates how both TBI and SCI affect an older patient’s ability to perform functional tasks and participate in community-related activities and employment (Fig. 26.1) (Salter et al., 2011). Strategic functional mobility interventions are implemented to address all established goals within the body structure/function, activity and participation domains. Outcomes may be measured through a variety of instruments, including the Functional Independence Measure, or FIM, which has shown appropriate psychometric support for patients with both SCI and TBI (Corrigan et al., 1997).

Traumatic brain injury

Over one million people sustain a TBI each year in the United States of America; moreover, TBI injuries account for one-third of all injury-related deaths (Faul et al., 2010; Brain Injury Association of America, 2012). The leading cause of TBI for those aged 65 or older is a fall-related episode, and current hospitalization rates continue to increase for individuals over the age of 80 who sustain head injuries (Bhullar et al., 2010). TBI is the principal cause of seizure disorders worldwide, and the World Health Organization adapted criteria for head injury surveillance in 1993.

Head injury sequelae can be devastating for a geriatric client and affect nearly every component of the quality of life, including self-care, employment and leisure activities. Poor recovery outcomes may warrant institutional placement if caregiving demands exceed available resources in the home environment. Fall prevention strategies for older clients are essential in preventing head injury. Geriatric individuals generally sustain falls secondary to either intrinsic or extrinsic causes. For example, intrinsic causes include sensory changes or vestibular pathology that impede effective balance modulation. Environmental barriers and obstacles resulting in trips and slips are included in the extrinsic category. Appropriate balance measures such as the Berg Balance Scale (Berg et al., 1992) or Timed Up and Go Test (Posiadlo & Richardson, 1991) can assist in identifying those clients most at risk for falling.

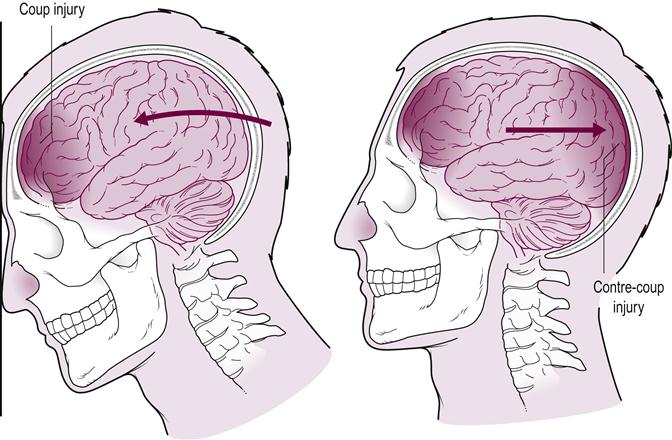

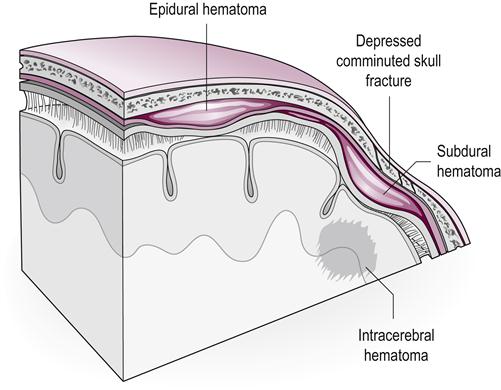

Head injuries may be characterized as either open or closed; open head injuries involve open penetration to the skull. The initial site of impact following a traumatic insult to the brain is known as the coup injury. A rebound effect often occurs in the cranium following the initial impact and causes a contre-coup injury (Fig. 26.2). Patients may also sustain additional complications because of skull fractures or hematomas. Skull fractures vary from relatively nonthreatening simple linear fractures to those with extensive comminuting fragments that require cranioplasty procedures (Fig. 26.3). Additionally, patients can incur complications such as internal organ damage or both spinal and extremity fractures. Patients may undergo extensive intensive care monitoring because of uncontrolled intracranial pressure or resultant seizure activity.

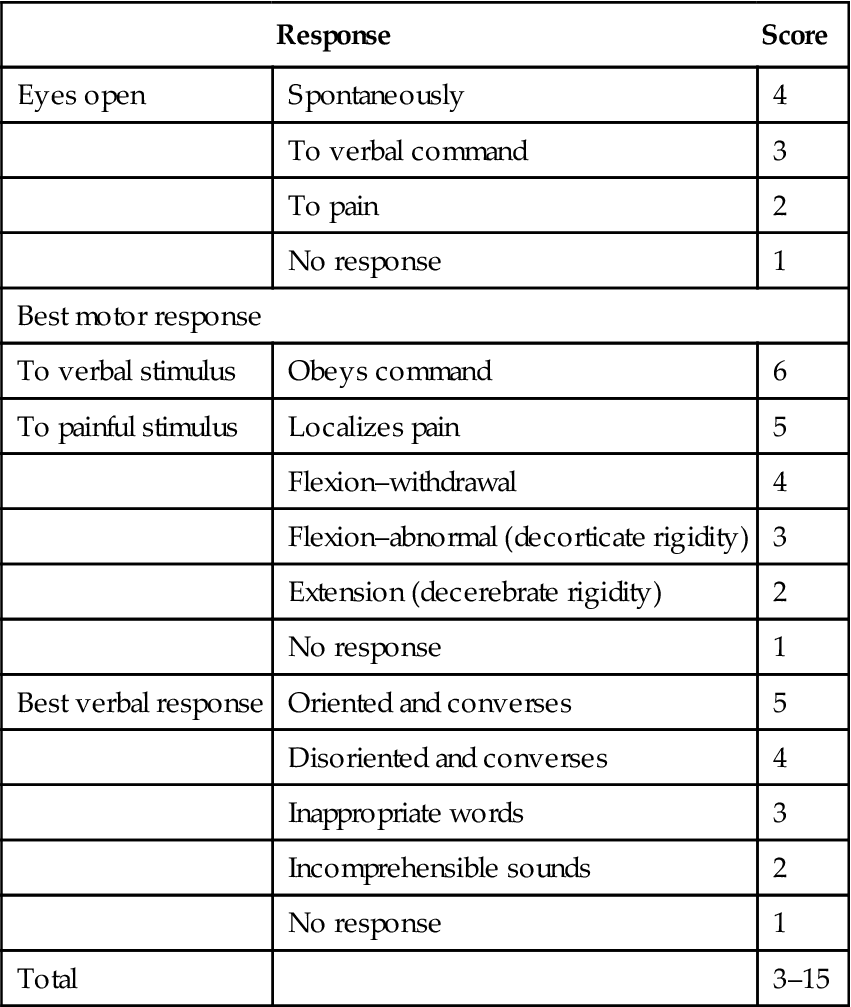

Initial trauma assessments are performed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Composed of three divisions, this instrument assesses three areas of function in individuals following head injury: motor performance, eye opening and verbal response (Table 26.1) (Teasdale & Jennett, 1974). Scores from 13 to 15 designate mild injury; from 9 to 12, moderate injury; and from 3 to 8, severe TBI. The rehabilitation team members should be aware of the initial GCS score and subsequent complications at the time of injury so that any examination or intervention activities can be adjusted. Patients’ prognostic functional recovery can be predicted by the initial FIM score, duration of post-traumatic amnesia and initial GCS score (Sandhaug et al., 2010).

Table 26.1

| Response | Score | |

| Eyes open | Spontaneously | 4 |

| To verbal command | 3 | |

| To pain | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| Best motor response | ||

| To verbal stimulus | Obeys command | 6 |

| To painful stimulus | Localizes pain | 5 |

| Flexion–withdrawal | 4 | |

| Flexion–abnormal (decorticate rigidity) | 3 | |

| Extension (decerebrate rigidity) | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| Best verbal response | Oriented and converses | 5 |

| Disoriented and converses | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| Total | 3–15 | |

Interventions for the geriatric client with a TBI include integrated strategies for both cognitive and neuromuscular impairments. Following recovery from a head injury, patients may be classified according to behavior associated with the Rancho Los Amigos Levels of Cognitive Function. Consisting of eight stages, this classification scheme illustrates progressive improvement from minimally responsive behavior to near full cognitive recovery (Table 26.2). This tool has been widely used to track such outcomes as patients’ functional recovery and hospital length of stay (Fakhry et al., 2004).

Table 26.2

Rancho Los Amigos levels of cognitive function

| I | No Response |

| II | Generalized response |

| III | Localized response |

| IV | Confused–agitated |

| V | Confused–inappropriate |

| VI | Confused–appropriate |

| VII | Automatic–appropriate |

| VIII | Purposeful–appropriate |

Levels I–III: coma emergence

The initial stages depict coma emergent behavior. Patients may progress from initially exhibiting no response to demonstrating a variety of localized responses such as a hand squeeze or facial grimace. The rehabilitation team members may elect to track progress through a standardized coma emergence rating form such as the JFK Coma Recovery Scale–Revised (Schnakers et al., 2009). Neurobehavioral assessments can aid in delineating between diagnostic criteria for minimally conscious and vegetative state conditions. Patients reaching maximum scores on these instruments may then have more advanced goals and intervention plans established. Patients emerging from minimally responsive states are progressively mobilized through tilt-table or standing-frame activities. Patients are started on a sitting schedule to gradually increase sitting time. A variety of sensory stimulation activities are utilized throughout functional tasks. Geriatric clients must be monitored carefully for vital sign fluctuations given premorbid medical conditions and adverse effects of bedrest acquired from extended intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring.

Level IV: the agitated client

Level IV depicts the agitated patient who cannot process the multitude of sensory experiences within the immediate environment. Individuals in this stage tend to exhibit disconcerted, agitated behavior, which often escalates to bursts of hostility. Therapists must adjust treatment activities by scheduling shorter treatment sessions or holding sessions in quiet areas to avoid sensory overload. Therapists should also model calm behavior and allow agitated patients to feel that they have control over the immediate situation. Treatment sessions are structured accordingly to avoid or minimize painful or fearful activities. The Agitated Behavior Scale is an instrument that documents levels of agitation among patients with TBI (Bogner et al., 2000).

Levels V–VIII: progressive cognitive recovery

In levels V–VIII, cognitive recovery progresses from behavior that is confused and inappropriate to eventual appropriate and purposeful behavior. Unfortunately, older clients who sustain more severe injuries and complications may not achieve full recovery. In addition, both cognitive and neuromuscular recovery may not occur in tandem. The ultimate challenge in geriatric head trauma rehabilitation focuses on integrating both cognitive and functional training strategies to effectively guide the patient towards maximal functional independence. The cognitive dimension of therapeutic interventions adds a level of complexity that necessitates specialized skills to facilitate psychomotor skill attainment and community re-entry.

Cognitive impairment following a TBI may be substantial. Patients demonstrate slower processing and require increased time to optimize task performance. A diminished attention span may also be apparent and patients require ongoing redirection to the designated task. Learning of functional skills occurs at a diminished rate and suitable time allotment and cue sequences must be constructed within a treatment session to optimize skill acquisition. Memory deficits may continue to be problematic. In addition, rehabilitation clinicians must be reminded that the issue of impaired judgment is still prominent in the final stages of the Rancho continuum. Patients at higher functional levels of mobility may still be unable to problem-solve in the event of an emergency situation.

Cognitive and functional interventions are merged in a variety of ways. For example, dual task activities are created to assess the patient’s problem-solving ability during functional tasks. Patients can be challenged to react in the event of an emergency situation. In addition, elements of memory can be incorporated by observing and reinforcing safety strategies taught during previous sessions. Patients may continue to have difficulty with advanced gait and balance activities such as tandem stance (Walker & Pickett, 2007), sensory reweighting tasks (Pickett et al., 2007) and running (Williams et al., 2012). At discharge, appropriate family training and instructions should be given to those family members who are caregivers for the older adult patient recovering from a TBI.

Spinal cord injury

It is estimated that 200 000 individuals are currently living in the US with activity and participation limitations sustained from SCI, with over 12 000 new cases sustained each year (Bernhard et al., 2005). This includes those individuals who are aged 65 years or older. Major causes of SCI worldwide include motor vehicle accidents, acts of violence and recreational activities. In addition, atypical causes globally in developing countries include falls from trees, injuries on construction sites and spinal injuries sustained while carrying heavy loads on the head (Lee et al., 2013). Injuries to the cervical spine often result in tetraplegia (also known as quadriplegia), with resultant impairments to all four extremities, the trunk and the pelvic organs. The term paraplegia indicates resultant lower extremity paralysis from a designated lesion occurring below the cervical spine and is associated with varying levels of trunk involvement in accordance with the lesion level. Functional outcomes parallel specific levels of function and benchmark muscles spared following an injury (Table 26.3). Geriatric clients may have similar causes of spinal cord pathology because of neoplasms or spinal stenosis conditions.

Table 26.3

Key muscles used to determine neurological classification of spinal cord injury (ASIA)

| Level | Muscle Groups Associated with Spinal Level |

| C5 | Elbow flexors (biceps brachii) |

| C6 | Wrist extensors (extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis) |

| C7 | Elbow extensors (triceps) |

| C8 | Finger flexors (flexor digitorum profundus) |

| T1 | Small finger abductors (abductor digiti minimi) |

| L2 | Hip flexors (iliopsoas) |

| L3 | Knee extensors (quadriceps) |

| L4 | Ankle dorsiflexors (tibialis anterior) |

| L5 | Long toe extensors (extensor hallucis longus) |

| S1 | Ankle plantar flexors (gastrocnemius/soleus) |

Sensory levels are utilized to determine C1–4, T2–L1 and S2–5 neurological levels.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree