11 Neurological disorders

CEREBRAL PALSY (Spastic paralysis: spastic paresis; Little’s disease)

The term cerebral palsy embraces a number of clinical disorders, mostly arising in childhood, the feature common to all of which is that the primary lesion is in the brain. The incidence of these disorders is such that cerebral palsy constitutes a major social and educational problem.

Types. A number of clinical types may be recognised, of which the most important are:

SPASTIC PARESIS

Clinical features. Usually within the first year it is noticed that the child has difficulty in controlling the movements of the affected limbs, and there is delay in sitting up, standing and walking. Commonly the upper and lower limbs of one side are affected (hemiplegia). Less often there is involvement of a single limb (monoplegia), of both lower limbs (paraplegia), or of all four limbs (tetraplegia1). The trunk and face muscles may also be affected. On examination the features that are found constantly are weakness, spasticity, and imperfect voluntary control of movement. Usually there is also deformity, and in some cases there may be mental deficiency, impaired vision, or deafness. These various features are best considered separately.

Corrective splinting. Splints or plasters are especially useful in overcoming the deformities induced by spastic muscles. Deformity is first corrected by gradual stretching of the contracted muscles, if necessary under anaesthesia. The limb is held by plaster in the over-corrected position for 6–8 weeks. Thereafter removable braces or splints (orthoses) may be used indefinitely to prevent recurrence of the deformity.

SPINA BIFIDA

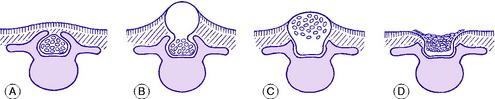

The term spina bifida implies a failure of the enfolding of the nerve elements within the spinal canal during early development of the embryo. The defect varies in degree and in its site (Fig. 11.1). In the mildest cases there is no more than a failure of fusion of one or more of the vertebral arches posteriorly, in the lumbo-sacral region. This is often of no clinical significance. Less often, the posterior bony deficiency is marked on the surface by an abnormality of the overlying skin, in the form of a dimple, a tuft of hair, a lipomatous mass, or a dermal sinus. In these cases there may be an underlying abnormality involving nerves of the cauda equina. These relatively minor varieties of spina bifida, in which the defect is not obvious at the skin surface, are termed spina bifida occulta. This contrasts with spina bifida aperta, in which there is a major defect of enfolding of the nerve elements, involving not only the bony vertebral arches but also the overlying soft tissues and skin, and often the meningeal membranes enclosing the spinal canal, so that the neutral tube itself is exposed and open. This major variant of spina bifida may occur anywhere in the spine but is commonest in the thoraco-lumbar region, and it is attended by grave impairment of nerve function.

SPINA BIFIDA OCCULTA (Occult spinal dysraphism)

As noted above, the bony defect is simply a failure of fusion of the vertebral arches posteriorly (Fig. 11.1A). When there is neurological involvement the overlying skin nearly always shows an abnormality, as already described.

In cases of occult spinal dysraphism there is no close correlation between the severity of the bony defect and the degree of neurological impairment. Often there is no neurological involvement; but on the other hand it may be severe. Clinically, the common manifestation of nerve involvement is muscle imbalance in the lower limbs, often with selective muscle wasting and deformity of the foot which often takes the form either of equino-varus or of cavus.