Neurologic running injuries account for a small number of running injuries. This may be caused by misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis. Nerve injuries that have been reported in runners include injuries to the interdigital nerves and the tibial, peroneal, and sural nerves. In this article, the etiology, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of these injuries are reviewed. Differences between nerve injury and more common musculoskeletal injury have been presented to aid in differential diagnosis.

The early 1980s saw a dramatic increase in the number of people participating in running. In Canada the percent of the population running increased from 15% to 31% between 1976 to 1983. The rise in running brought a focus in the sports medicine world to running-related musculoskeletal injuries, and their epidemiology and biomechanics.

Over time, training programs, footwear design, and the running demographic have evolved; however, the injury rate remains high, with 35% to 65% of runners reporting injury. The most common location of injury is the knee, followed by the foot. The recent retrospective analysis by Taunton and colleagues reported patellofemoral pain syndrome, iliotibial band friction syndrome, and plantar fasciitis as the three most common diagnoses.

Of the many running injuries that are reported, few are neurological in nature. A 1983 epidemiological study reported that 5.7% of peripheral nerve injuries were sports related. Furthermore, a study on peroneal nerve entrapment reported diagnosing eight athletes over 18 years of practice (seven runners and one soccer player). All eight were diagnosed in the last 7 years, which the authors suggest could be secondary to increased awareness of nerve involvement or to a general increase in running activity.

Despite these reports, neurologic injuries are thought to be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed. Symptoms may present differently, depending on the degree and location of the impingement, and often require exercise to reproduce the pain. In addition, they may accompany other common running injuries, making differential diagnosis difficult. Often persistence of injury leads to implication of nerve involvement.

This article describes the etiology of nerve injuries in runners, and discusses associated musculoskeletal injuries and their differential diagnosis and treatment options.

Interdigital nerves

The interdigital nerves arise from the medial and lateral plantar nerves, which branch from the tibial nerves. They course distally, under the transverse metatarsal ligament, along the metatarsals, and terminate at the distal phalanges. Morton’s neuroma is an impingement of one of the interdigital nerves. Although it is referred to as Morton’s neuroma, it is actually not a tumor of nerve cells as indicated by the name, but is characterized by fibrosis and demylenation of the nerve. This is thought to be caused by repetitive dorsiflexion of the toes, causing microtrauma to the nerve as it is compressed either under the transverse metatarsal ligament or by an inflamed intermetatarsal bursa. It can occur between any of the metatarsals, but most commonly occurs in the third interdigital space, followed by the second interdigital space.

Although the incidence in both athletes and the general population is unclear, it is considered to be a common cause of forefoot pain. It is exacerbated by repetitive dorsiflexion of the toes, characteristic of the end of the stance phase in running, and by tight fitting footwear. A higher incidence has been documented in females compared with males, possibly caused by footwear differences.

Symptoms

Forefoot pain radiating to the affected interspace and numbness and tingling in the toes and interdigital space are common. Pain may be relieved with gentle massage and avoiding footwear. Pain is increased with weight-bearing activity and compression of the metatarsal heads. The latter, combined with palpation of the interdigital space, may reproduce the pain and cause clicking. This is referred to as Mulder’s click.

Diagnosis

The physical examination should include a clinical history, Mulder’s maneuver, and palpation of the adjacent metatarsals, phalanges, and metatarsalphalangeal joints to differentiate nerve involvement from other musculoskeletal injuries. In the case of multiple affected interspaces, more proximal nerve damage should be considered. Palpation of the proximal foot structures are indicated to determine the location of the compression.

Imaging techniques can be used to aid in diagnosis; however, nonspecific interdigital masses have been found in 33% of patients who have no clinical symptoms of Morton’s neuroma. Therefore, weight is placed on the clinical history. Ultrasound can be used to confirm the clinical diagnosis and site of impingement. This has been shown to be more effective when done dynamically, using Mulder’s maneuver. It has also been successfully used to diagnose recurring injury post-surgery. MRI is useful to rule out other orthopedic injuries where necessary.

Treatment

Conservative treatment options include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories and modifications to training and footwear. Properly fitting footwear providing adequate width to accommodate the forefoot is essential. A metatarsal pad placed proximal to the affected interspace can be used to alleviate pressure on the affected nerve. Traditional orthotics to prevent pronation or supination have been shown to have no effect on symptoms, either positive or negative. If symptoms persist, corticosteroids can be injected into the interdigital space. Although the success of conservative treatment depends on the severity of the impingement, 85% reported improvement with the protocol described. Twenty-one percent of patients in this study had persistent symptoms warranting surgical options.

Although nonoperative treatments should be explored first, the success of surgery for more severe cases has been positive. Using the nerve resection technique, Bennett and colleagues reported a satisfactory result in 96% of patients. Some controversy exists over the surgical method. Initially, the surgical approach was to excise the impinged intermetatarsal nerve via either a plantar or dorsal approach. In 1979, Gauthier advocated transection of the intermetatarsal ligament to decompress the nerve, leaving the nerve intact. Further evolution of the surgery has included a minimally invasive endoscopic technique of transecting the ligament. Another minimally invasive technique uses an instrument for releasing carpal tunnel syndrome. Using this technique, 11 of 14 patients were symptom-free post-surgery.

Failure to respond to both nonoperative and operative treatments may suggest the presence of other foot pathologies.

Tibial nerve

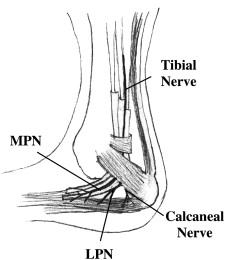

The tibial nerve arises from the sciatic nerve superior to the popliteal fossa, and courses distally through the posterior lower leg. In athletes, entrapment of the tibial nerve generally only occurs at the foot and ankle region. The most common location is around the posterior edge of the medial malleolus within the tarsal tunnel, where the nerve passes to extend into the foot ( Fig. 1 ). The walls of the tarsal tunnel are created by the flexor retinaculum, calcaneus, talus, and medial malleolus. Several structures run through the tarsal tunnel, including the tendons of the tibialis posterior, flexor hallicus longus, flexor digitorum longus, and the posterior tibial artery and nerve. Because of the inelasticity of the tunnel, any enlargement of the structures inside can increase pressure within the tunnel, causing nerve compression.

Generally, nerve injury in this area is secondary to another pathology. For runners, this may be inflammation of the synovial sheaths lining the tendons (tenosynovitis), accessory muscles, fracture, or more rarely, ligament fibrosis from chronic ankle sprains. Nerve compression may occur via the mechanism described above or with tension on the tibial nerve with pronation of the subtalar joint. Injury to the structures of the tunnel is thought to be caused by the repetitive plantar flexion and dorsiflexion at the ankle occurring while running. Furthermore, poor mechanics, such as excessive pronation, valgus deformity, or flat feet exacerbate the problem.

Kinoshita and colleagues reported surgically treating 58 feet that had tarsal tunnel syndrome over a 16-year period; 39.1% of these were sport-related injuries. Although this injury rate appears low, tarsal tunnel syndrome is thought to be underdiagnosed because of the similarity in symptoms to plantar fasciitis, heel pad atrophy, and calcaneal fractures. Plantar fasciitis is the third most commonly diagnosed injury in runners. It is possible that more cases with nerve involvement present within this population, but are not differentially diagnosed.

Symptoms

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is characterized by local tenderness behind the medial malleolus and numbness, tingling, and pain over the medial heel, arch, medial sole, or sole of the foot. Pain can be burning, sharp, shooting, or dull, and may radiate proximally up the calf or distally into the foot. Pain is usually decreased with rest and increased at night, and with weight bearing, prolonged standing, running, and the initial steps after rest. The latter is referred to as post-static dyskinesia, and is characterized by the accumulation of fluid around an injury during rest, which causes increased pressure on the nerve with subsequent weight bearing. Foot weakness has also been reported.

Although these are the general symptoms for TTS, symptoms vary depending on the exact location of compression of the tibial nerve or its branches ( Table 1 ). Although the location of nerve branches varies among individuals, all three nerve branches originate in the region of the tarsal tunnel and have been implicated in heel pain. A recent review of neural heel pain differentiated symptoms according to the nerve branch affected. Lateral plantar nerve (LPN) symptoms have been described as affecting the medial calcaneus and proximal plantar fascia area with maximum tenderness over the nerve. Medial plantar nerve (MPN) symptoms occur over the medial arch and navicular tuberosity. Anterior calcaneal nerve symptoms manifest in the medial fat pad and abductor hallucis, with reduced symptoms over the plantar fascia.

| TTS | PF | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Numbness, tingling and pain in medial heel, arch, medial sole and sole | Pain in calcaneal tuberosity, origin of plantar fascia, midfoot fascia |

| Sharp, shooting, dull, radiating | Localized | |

| Decreased with rest | ||

| Increased at night, running, post-static dyskinesia | Post-static dyskinesia | |

| Foot weakness | ||

| LPN—medial heel, proximal pf area, tender medial foot | ||

| MPN—laterally on medial arch, navicular tuberosity | ||

| Calcaneal nerve—medial fat pad, abductor hallucis, less over plantar fascia | ||

| Diagnosis | History and physical | History and physical |

| Tinel’s | ||

| Sensory and motor nerve conduction of LPN, MPN | ||

| QST | ||

| Two-point discrimination | ||

| Modified straight leg test |

The important differential diagnosis in this case is plantar fasciitis, in which symptoms may be slightly different, but which occurs in the same region (see Table 1 ). Plantar fasciitis is characterized by pain at the calcaneal tuberosity, or origin of the plantar fascia, continuing a few centimeters distally along the fascia over the midfoot. The pain is more localized than tarsal tunnel syndrome, and does not include the paraesthesia or sensory deficit associated with nerve involvement. Post-static dyskinesia may also be present with plantar fasciitis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of TTS relies on a history and physical examination. In addition to the symptoms described above, swelling over the tibial nerve may be palpable. Patients experience pain on tapping the nerve (positive Tinel’s sign), and may exhibit loss of two-point discrimination. The dorsiflexion-eversion test was initially introduced as a diagnostic tool for TTS that reproduces nerve pain by placing the foot in dorsiflexion and eversion with the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints extended. The windlass test was developed to reproduce plantar fasciitis pain by extending the MTP joints with a neutral ankle. Although these diagnostic tests may aid in injury differentiation, both tests increase the strain in the tibial and plantar nerves as well as the plantar fascia. Alternatively, adding a straight leg raise after dorsiflexion and eversion has been shown to further increase the strain on the tibial nerve. This modified test may be useful in differential diagnosis in the future.

Additional tools may be used to confirm physical examination findings, including ultrasound, radiography, quantitative sensory tests, and electrodiagnostics. Abnormal motor and sensory nerve conduction have been shown with nerve damage; however, results have been variable, and therefore the accuracy has been a topic of many studies. In 2005, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine sponsored an effort to evaluate the existing research and determine the usefulness of these tools. It was concluded that sensory nerve conduction was more sensitive than motor nerve conduction in identifying nerve injury, but less specific. Current recommendations are to use nerve conduction velocity in conjunction with physical examination and to include both motor and sensory tests of the medial and lateral plantar nerves. Exposing the injured dermatome to some form of stimulus (temperature, vibration and so forth) is referred to as quantitative sensory testing. This type of test has also shown some success in identifying nerve injury, although its use for TTS has been limited thus far.

Together, these tests, along with Tinel’s sign, two-point discrimination, and potentially the modified straight leg test, will help differentiate TTS from a pure musculoskeletal injury such as plantar fasciitis (see Table 1 ).

Treatment

Initial treatment of TTS is conservative, using rest, ice, physiotherapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, corticosteroids, and footwear modifications. Eliminating excessive pronation using varus orthotics or medially posted shoes may alleviate pain and help treat the source of the problem. This is important to correct any abnormal mechanics that may inhibit healing, especially for runners who undergo repetitive motion at the ankle.

Initial treatment of tarsal tunnel syndrome and plantar fasciitis are similar; however, if the symptoms persist, then surgical intervention is an option and differential diagnosis becomes important. Surgical procedures involve decompressing the tibial nerve (or involved branches) while repairing the secondary pathology responsible for increased tunnel pressure. This may involve dissection of the flexor retinaculum, neurolysis of the affected nerve, tenosynovectomy, excision of bony fragments, stretching of the neurovascular bundle around foot deformities, or removal of accessory muscles. Pain relief can be immediate; however, a 3-month postsurgical recovery followed by a gradual return to sport is recommended to get rid of all symptoms and avoid reinjury. Kinoshita and colleagues reported a complete return to sport in 12 of 18 athletes postsurgery.

Tibial nerve

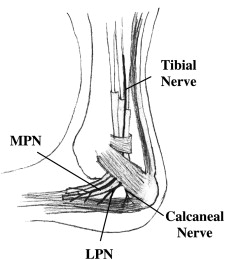

The tibial nerve arises from the sciatic nerve superior to the popliteal fossa, and courses distally through the posterior lower leg. In athletes, entrapment of the tibial nerve generally only occurs at the foot and ankle region. The most common location is around the posterior edge of the medial malleolus within the tarsal tunnel, where the nerve passes to extend into the foot ( Fig. 1 ). The walls of the tarsal tunnel are created by the flexor retinaculum, calcaneus, talus, and medial malleolus. Several structures run through the tarsal tunnel, including the tendons of the tibialis posterior, flexor hallicus longus, flexor digitorum longus, and the posterior tibial artery and nerve. Because of the inelasticity of the tunnel, any enlargement of the structures inside can increase pressure within the tunnel, causing nerve compression.

Generally, nerve injury in this area is secondary to another pathology. For runners, this may be inflammation of the synovial sheaths lining the tendons (tenosynovitis), accessory muscles, fracture, or more rarely, ligament fibrosis from chronic ankle sprains. Nerve compression may occur via the mechanism described above or with tension on the tibial nerve with pronation of the subtalar joint. Injury to the structures of the tunnel is thought to be caused by the repetitive plantar flexion and dorsiflexion at the ankle occurring while running. Furthermore, poor mechanics, such as excessive pronation, valgus deformity, or flat feet exacerbate the problem.

Kinoshita and colleagues reported surgically treating 58 feet that had tarsal tunnel syndrome over a 16-year period; 39.1% of these were sport-related injuries. Although this injury rate appears low, tarsal tunnel syndrome is thought to be underdiagnosed because of the similarity in symptoms to plantar fasciitis, heel pad atrophy, and calcaneal fractures. Plantar fasciitis is the third most commonly diagnosed injury in runners. It is possible that more cases with nerve involvement present within this population, but are not differentially diagnosed.

Symptoms

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is characterized by local tenderness behind the medial malleolus and numbness, tingling, and pain over the medial heel, arch, medial sole, or sole of the foot. Pain can be burning, sharp, shooting, or dull, and may radiate proximally up the calf or distally into the foot. Pain is usually decreased with rest and increased at night, and with weight bearing, prolonged standing, running, and the initial steps after rest. The latter is referred to as post-static dyskinesia, and is characterized by the accumulation of fluid around an injury during rest, which causes increased pressure on the nerve with subsequent weight bearing. Foot weakness has also been reported.

Although these are the general symptoms for TTS, symptoms vary depending on the exact location of compression of the tibial nerve or its branches ( Table 1 ). Although the location of nerve branches varies among individuals, all three nerve branches originate in the region of the tarsal tunnel and have been implicated in heel pain. A recent review of neural heel pain differentiated symptoms according to the nerve branch affected. Lateral plantar nerve (LPN) symptoms have been described as affecting the medial calcaneus and proximal plantar fascia area with maximum tenderness over the nerve. Medial plantar nerve (MPN) symptoms occur over the medial arch and navicular tuberosity. Anterior calcaneal nerve symptoms manifest in the medial fat pad and abductor hallucis, with reduced symptoms over the plantar fascia.

| TTS | PF | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Numbness, tingling and pain in medial heel, arch, medial sole and sole | Pain in calcaneal tuberosity, origin of plantar fascia, midfoot fascia |

| Sharp, shooting, dull, radiating | Localized | |

| Decreased with rest | ||

| Increased at night, running, post-static dyskinesia | Post-static dyskinesia | |

| Foot weakness | ||

| LPN—medial heel, proximal pf area, tender medial foot | ||

| MPN—laterally on medial arch, navicular tuberosity | ||

| Calcaneal nerve—medial fat pad, abductor hallucis, less over plantar fascia | ||

| Diagnosis | History and physical | History and physical |

| Tinel’s | ||

| Sensory and motor nerve conduction of LPN, MPN | ||

| QST | ||

| Two-point discrimination | ||

| Modified straight leg test |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree