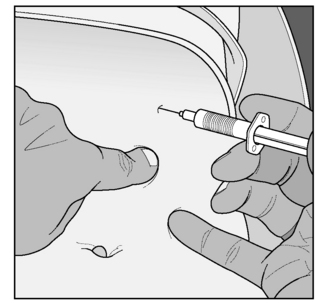

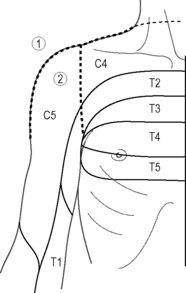

Chapter 7.12 Neural therapy Neural therapy is considered to be a regulatory and system-resetting therapy in which local anesthetics (LA) are injected in defined regions of the body. Homeostasis is thought to be re-established by extinguishing peripheral irritation and stimulating regulatory processes (Perschke 1989; Gross 1986, 1988; Heine 2006). Procaine is the preferred LA, due to its short duration of action and its positive effect on tissue perfusion; the latter also probably due to its metabolites (para-aminobenzoic acid and diethylaminoethanol). It is also assumed to influence cytokine metabolism (IL6, TNF-alpha, CRP) and activate the endocannabinoid system (Travell & Simons 1983; Heine 2006). The anti-inflammatory effect of LA has recently been discovered (Hollmann & Durieux 2000). The anti-inflammatory effect is independent from the sodium channel action of LA. It lasts much longer than the anesthesia induced by LA. This is perhaps one of the most important explanations of the therapeutic properties of LAs. This mechanism also explains their relaxing effect on muscular trigger points (Heine 2006). In addition, LA reduces neurogenically induced inflammation by influencing neurotransmitters (Tracey 2009; Oke & Tracey 2009). LA also seem to have remarkable effects on the immune system (Cassuto et al. 2006; Rosas-Ballina & Tracey 2009). The application of neural therapy is recommended only after the relevant knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology has been acquired, and after a thorough training in the application of the therapy (for standards, see Weinschenk 2010 and Fischer 2007). All LA inhibit autonomic nerve conduction and therefore have a sympathetic inhibitory effect. These properties are connected with their influence on protein structures in the matrix (intercellular substance) (Pischinger & Heine 2007; Papathanasiou 2010). Neural therapy is further based on segmental reflex mechanisms: all impulses coming from the periphery (peripheral nervous system) converge in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (the central nervous system). Impulses originating from the cutis and subcutis, from joint structures, tense muscles and affected organs, from scars or injuries may become pathological. In the dorsal horn, they are normally eliminated by descending inhibitory systems and the patient remains symptom free. If these impulses become too strong, or if the inhibitory systems are impaired, there is a relay in three directions: via the anterolateral tract for the cortical perception of pain, via the motor anterior horn for the muscles, and via the lateral sympathetic horn and the sympathetic tract, which is connected to the peripheral nervous system. The anatomical interconnection of these pathways causes a positive feedback of the impulses through several segments (Jänig 1987). These horizontal segmental projections may also be projected vertically beyond the segments by the muscular, fascial, sympathetic, and parasympathetic systems as well as the so-called functional chains, e.g. affected tooth → disorder of the cervical joints → functional scoliosis → disorder of the sacroiliac joint → lumbago (Wancura 2010, Wander 1992). The focus here is the neurologically defined segment of the spinal and cranial nerves. A segment consists of all structures innervated by one spinal nerve: cutis, subcutis, joints (also spinal joints), joint capsules, muscles, fascia, bones, and viscera. Every part of the segment reacts simultaneously on external stimuli of any other part, probably due to the convergence of all segmental impulses on the spinal level (Sessle et al. 1986). A therapeutic stimulus applied in one segment can influence another part of the segment. The easiest way to apply a stimulus is by intracutaneous injection in the appropriate dermatome, thereby producing a small papule or wheal. Example 1 Patient with shoulder pain (segment C4 and C5): two intracutaneous routes of papules (wheals): the first route goes from the C7 spinous process to the acromion and to the base of the deltoid muscle (segments C4 → C5 → Th2) and the second goes from the anterior axillary fold on the acromion to the posterior axillary fold (segments Th2 → C5 → C4). In this way, adjacent segments with ancillary function to the shoulder joint (ACG, SCG, clavicle, first and second rib) may also be included (Fig. 7.12.1). Fig. 7.12.1 • Injection routes in a patient with shoulder pain. Example 2 Patient with gastrointestinal symptoms in the upper abdomen: Injections of intracutaneous papules/wheals and subcutaneous injections in the area of the costal arch (so-called Vogler points, Fig. 7.12.2) and the fascia of the abdominal muscles. The xyphoid process (a rudiment of the seventh rib) is of special significance in this region and belongs to the T7 segment. The duodenum and the pancreas belong to the same segment. Because of the segmental organization of skin, muscle, fascia, and periosteum there is a connection between these structures and the stomach, the pancreas and the small intestine, through which these organs can in turn be influenced. Intracutaneous and deeper prefascial injection can also be applied in the anterior midline at acupuncture point CV12 (see Fig. 7.12.2). This point is connected with the celiac ganglion, which controls the sympathetic abdominal organs (Heine 2006; Wancura 2010). Acupuncture points are considered to be passage points in the fascia (Heine 2006) through which nerves, blood and lymphatic vessels come to the surface. It is suggested that these structures can be influenced by injecting procaine at one of these points as well. Therefore neural therapists also choose acupuncture points for treatment (Heine 2006). If the segmental injections are not sufficient to improve the patient’s symptoms, the clinician may block the afferent stimulus at the level of the spinal nerves, the plexus, the vessels, the sympathetic or parasympathetic ganglia (so-called extended segment therapy). By eliminating the afferent and efferent impulses, as well as simultaneously activating the descending endogenous inhibitory systems, the auto-organization of the peripheral nervous system can recover (see also Oke and Tracey 2009). In the patient with shoulder pain (Example 1), this could be achieved by an injection into the stellate ganglion or the axillary plexus. In the patient with gastric problems (Example 2), extended segment therapy would consist of injection into the sympathetic celiac ganglion. In addition, an injection into the associated vertebral facet joints in the vicinity of the sympathetic trunk can be applied (indirect injection to the sympathetic trunk) (Kupke 2010), which affects 80% of the sympathetic afferent and efferent nerve fibers of the corresponding segment.

Introduction

Neuroanatomy

Procedure

Segment therapy

Internal organs can also be influenced using the knowledge of the cutivisceral and visceromotoric reflex arcs.

Extended segment therapy, ganglia therapy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine