Chapter 31 Nerve Entrapment Around the Elbow

Background/aetiology

The clinician should also be aware that occasionally a ‘double-crush’ phenomenon may occur. This was first described by Upton and McComas1 in 1973 who stated that ‘neural function was impaired because single axons, having been compressed in one region, become especially susceptible to damage at another site’. When this occurs in the upper limb the peripheral nerves become hypersensitized by proximal compression in the neck and are more susceptible to an otherwise well-tolerated level of compression.

The causes of compression can vary widely and are given below.

The anatomical structures around the elbow and, in particular, the various fibro-osseous tunnels and fibrous arches can cause rigid borders against which nerves may be compressed. The large range of elbow flexion will produce longitudinal traction on the nerves lying within the extensor compartment whilst compressive forces are applied to the nerves on the flexor surface. The ulnar nerve for example is subjected to longitudinal traction during terminal flexion. In addition it has been reported that 5.1 mm of ulnar nerve excursion is needed for elbow motion from 10° to 90°.2 This alone may compromise nerve function, but when combined with a second local insult such as a fibrous band or impinging osteophyte there is an increased likelihood of nerve irritation.

Congenital abnormalities can also produce nerve entrapment. The median and very occasionally the ulnar nerve may be compromised by the ligament of Struthers. This arises from a supracondylar spur on the medial border of the distal humeral shaft and extends obliquely to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 31.1).

Figure 31.1 (A) Supracondylar process: anteroposterior view. (B) Supracondylar process: lateral view.

Cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar nerve)

Background and aetiology

The ulnar nerve at the level of the elbow is a large mixed motor and sensory nerve. It provides sensation to the ulnar one and a half digits of the hand, the volar and dorsal aspect of the hand and the medial aspect of the forearm. It is the motor supply to FCU, flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), palmaris brevis, adductor pollicis, the deep head of flexor pollicis brevis, seven interossei, three hypothenar muscles and the lumbricals to the little and ring fingers. With severe ulnar nerve compression at the elbow, the commonest site of muscle wasting, is the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Fig. 31.3).

The intraneural anatomy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is organized into a layered formation of fibres.3 Sunderland showed that the sensory supply to the hand was present in the most superficial layer beneath which was found the innovation of the intrinsic muscles. The motor branches to the long flexor tendons were present in the deepest portion of the nerve. This patterning explains the early onset of sensory symptoms in the hand and why weakness of the long flexor tendons occurs at a much later stage with more significant compression.

The ulnar nerve blood supply is segmental and is a major concern during anterior transposition when the nerve is solely dependent on its intraneural supply. Prevel et al4 in a study on the extrinsic blood supply showed that the ulnar nerve receives two constant major pedicels from the superior ulnar collateral artery proximally and the posterior ulnar recurrent artery distally. In a cadaveric study they demonstrated by measuring total vessel length and distance to the medial epicondyle that the extrinsic vascular supply could be preserved during anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve, even after the nerve had been extensively mobilized. Simple decompression, however, has the advantage of leaving the nerve in situ with its surrounding vascular supply.

The ulnar nerve can be compressed at four main sites around the elbow:

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Investigations

An ultrasound scan may be a useful test to visualize the ulnar nerve in cases of suspected subluxation in the larger obese patient. It will also reveal the lack of nerve excursion and movement on flexion and will show sites of tethering and compression. In addition it may indicate neural swelling proximal to the site of compression.5

Treatment options

Non-operative treatment

The non-surgical management of ulnar neuropathy should be restricted to mild to moderate entrapment.9 Simple analgesics and non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs may be useful for some patients. Others find splints beneficial although rigid devices are often poorly tolerated by both the patient and their bed-time partner. As a short-term measure we advise the patient to make a hole at the far end of a pillowcase. The hand can be passed through the pillowcase, alongside the pillow exiting on its far side through a small window that has been cut in the seam. During rest at night, flexion of the elbow, which often accompanies patients who sleep in the fetal position, is prevented. The elbow is unable to flex due to the bulky pillow. Patients often find this useful and more comfortable than other types of splint. In our experience, however, spontaneous resolution of symptoms is unlikely if the nerve entrapment syndrome is secondary to osteoarthritis, if there is a significant bony deformity such as cubitus valgus; or, if the compression appears to be severe, with significant motor wasting or sensory loss.

Surgical technique and rehabilitation

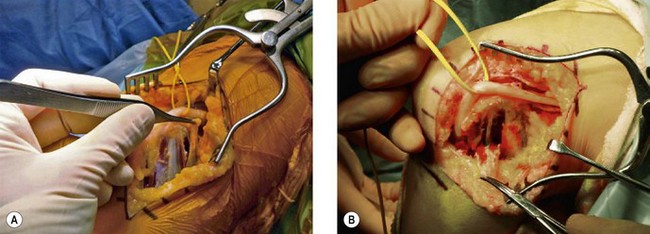

Simple decompression

Simple decompression is adequate for the vast majority of patients and can be performed through a relatively small incision that preserves the vascular bed of the nerve. The ulnar nerve is identified proximal to the elbow on the medial aspect of the arm. It can be felt as a rubbery cord. Having mobilized the skin edges, the nerve can be released for 10–15 cm proximal to the skin incision using appropriately angled retractors. Osborne’s fascia is then released between the two heads of the FCU (Fig. 31.5). In simple decompressions the medial intermuscular septum is not excised or released. Having completed the decompression the tourniquet is released, bleeding controlled and the wound closed with a subcuticular suture.

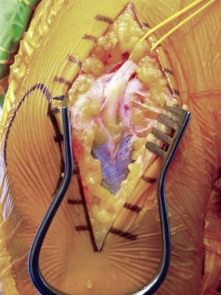

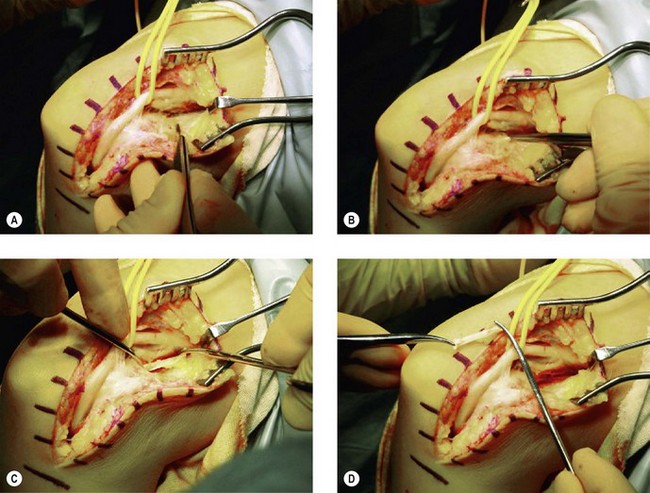

Subcutaneous anterior transposition

Having positioned the patient and undertaken the incision as previously described the ulnar nerve is identified as it passes beside the medial intermuscular septum. A 4 cm strip of the septum is then excised in order to allow the nerve to remain in the anterior compartment once it has been transposed. Distally the ulnar nerve is released for 5 cm as it passes down between the two heads of the FCU. The nerve can then be mobilized from its bed, preserving its longitudinal blood supply. The new bed for the ulnar nerve is then prepared. The fat is mobilized off the common flexor fascia for approximately 8–10 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle. A fascial strip is then elevated, as shown in Figure 31.6A. The nerve is transposed anteriorly and the fascial strip (Fig. 31.7) looped around the nerve and sutured back onto itself, securing the nerve in its anteriorly transposed position (Fig. 31.8). It is of vital importance that the ulnar nerve does not travel through any sharp angles, proximally, distally or underneath the fascial loop. In particular, the fascial loop should be loose and not cause any compression of the nerve. The transposed nerve should be tension free. The tourniquet is released, haemostasis achieved and the wound closed with a subcuticular suture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree