Nerve Decompression

Robert J. Spinner

ULNAR NERVE

Indications/Contraindications

Nonoperative management is appropriate when progressive objective signs of neuropathy are not present. This consists of instructing the patient to avoid leaning on the elbow on the inner aspect and prolonged elbow flexion; a long arm splint with the elbow at 70 degrees of flexion, the forearm in midposition, and the wrist in neutral position, is worn full-time for approximately 4 to 6 weeks. With improvement, the splint is then used only at night for an additional 2 to 3 months. If the patient improves with this management, as happens in about 50% of cases, surgery can be avoided.

The patient is followed clinically for his or her subjective complaints. Often the numbness that is in the little finger improves after 10 days; on occasion, symptoms are relieved within a day or two. Weakness of the hand is a common finding in ulnar paresis. Even without clawing of the fingers, there may be weakness of the intrinsic muscles. In my experience, the pinch dynamometer mirrors the electromyographic (EMG) studies. If the strength improves, so too does the electrical conduction across the elbow.

With clinical improvement, the nonoperative treatment is continued, usually for 3 months. After removal of the night splint, the patient is instructed not to sleep with the elbow fully flexed, but rather to put it out straight or on a pillow at night. If necessary a 70-degree flexion splint can be worn. Certainly, if the condition recurs, and there is no evidence of atrophy of the intrinsic muscles, the splint can be worn for an additional 6- to 8-week period if necessary.

Surgery is indicated when the sensory loss does not subside, and if there is progressive atrophy of the intrinsic muscles and weakness as observed with the pinch dynamometer. Serial electrodiagnostic studies in this instance, if performed, reveal slowing of conduction of the ulnar nerve across the elbow, and fibrillations and sharp waves in the ulnar nerve innervated intrinsic muscles. Surgery is also indicated in certain instances associated with fractures or dislocations. If the ulnar nerve is entrapped or impaled by fracture fragments, or trapped in the joint following reduction of a dislocation, early surgery is appropriate. If an open injury exists or if open reduction of the fracture is necessary, then primary concomitant surgical evaluation and management of the ulnar nerve should be performed. Tardy ulnar nerve palsy may also require surgical intervention (14).

If confusing variables exist, such as worker’s compensation or pending litigation, surgical intervention should be considered very carefully and reluctantly.

Preoperative Planning

The correct localization of the lesion is vital. The patient can have a pure ulnar nerve lesion at the elbow or a double-crush lesion, most frequently at the elbow and the neck. Fibrillations on EMG studies in the cervical paravertebral muscle region would suggest a more proximal lesion. A conduction block across the elbow would confirm and localize the lesion to the elbow. Nevertheless, one can have a lesion at both regions in a double-crush lesion.

The usual sensory symptomatology of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is numbness in the dorsal and palmar aspects of the little finger and half of the ring finger. For clinical localization of the neural lesion to the elbow level, sensory loss on the dorsoulnar aspect of the hand is a

characteristic finding. With more proximal ulnar nerve involvement, that is, in the thoracic outlet, or neck, a different pattern of sensory disturbance involving the forearm or arm would be present. However, when the little finger is numb only on the palmar side, the ulnar nerve compression is usually at the level of the canal of Guyon.

characteristic finding. With more proximal ulnar nerve involvement, that is, in the thoracic outlet, or neck, a different pattern of sensory disturbance involving the forearm or arm would be present. However, when the little finger is numb only on the palmar side, the ulnar nerve compression is usually at the level of the canal of Guyon.

Motor involvement from an elbow level localization may result in paresis or paralysis of the flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus of the ring and little fingers, and the ulnar-innervated hand intrinsics.

A positive percussion sign and/or a positive elbow flexion text helps localize the problem to the elbow, but false positives are not uncommon findings in patients with “irritable” nerves. Dislocation of the ulnar nerve, with or without snapping on elbow flexion, is often associated with a positive percussion sign at the elbow level. It is also important to be sure that the patient who has a symptomatic dislocating and snapping ulnar nerve (5) does not have a coexistent snapping medial triceps (15,17). The dislocating ulnar nerve and snapping triceps can be diagnosed clinically preoperatively (and typically intraoperatively); it can be embarrassing to translocate the ulnar nerve anteriorly and have persistence of the snapping postoperatively with elbow flexion due to a triceps snap.

Surgery

Indications for specific types of ulnar nerve procedures remain controversial (12). In my practice, I have attempted to correlate EMG studies to the type of operative procedure. The simple release of the cubital tunnel retaniculum and the flexor carpi ulnaris arcade can be utilized in those cases in which the compression is at that site and the patient has persistent symptoms of mild ulnar neuropathy with minimal or no electrical findings after appropriate conservative care fails. Over the past few years, based on my own clinical experience and prospective comparative studies done by colleagues, I have also been performing simple releases more widely, even in cases of moderate neuropathy.

I have not been utilizing this procedure when a dislocating ulnar nerve is present. When ulnar nerve symptoms are caused by a dislocating ulnar nerve, it is best to perform anterior translocation since the soft tissue restraints typically released in an in situ decompression are not present. A completely dislocating ulnar nerve, in contrast to a subluxating nerve, rarely causes problems. However, thin patients with minimal subcutaneous fat may become symptomatic especially. A dislocating nerve may be vulnerable to friction over the medial epicondyle; a subluxating nerve may be susceptible to compression against the epicondyle or by direct trauma.

Anterior translocation of the ulnar nerve is a commonly practiced surgical procedure. I prefer the anterior translocation (either subcutaneous or submuscular) over in situ decompression, when there is electrical indication confirming the patient’s more severe ulnar nerve involvement especially when axonal degeneration is present. In more recent years, I have been utilizing the subcutaneous technique increasingly rather than the submuscular technique in primary cases with severe neuropathy.

Additional techniques are advocated by some other authors. I have not been placing the nerve intramuscularly, as I have often treat patients with recurrent neurologic symptoms after this technique. I do not recommend the modification of the Learmonth procedure in which the flexor-pronator muscles are detached directly from the epicondyle and reattached to it, or when the epicondyle is osteotomized. In addition, I do not perform medial epicondylectomy.

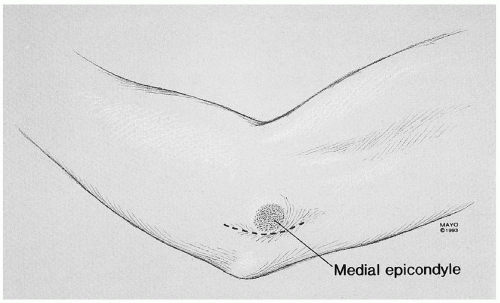

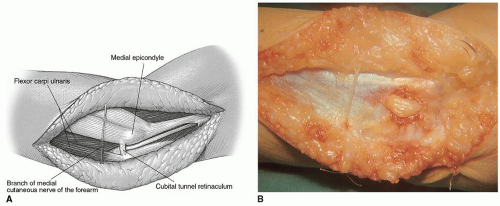

Isolated Decompression Without Translocation Monitored anesthetic care is utilized along with a tourniquet. The extremity is placed on an arm board after preparation and draping (Fig. 17-1). The arm is externally rotated, and a few folded sheets are placed under the elbow to elevate it. The medial aspect of the elbow is in view with the medial epicondyle prominent. When the ulnar nerve is not to be translocated, a longitudinal incision 6 cm long is made centered at the region of the cubital tunnel retinaculum. The terminal branches of the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm and the crossing branches of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm in the region of the olecranon should be preserved. They are found deep to the fat just superficial to the fascia overlying the flexor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 17-2). A rubber band is placed about each of them so they can be retracted. The ulnar nerve, which passes longitudinally just deep to the aponeurotic origin of the flexor carpi ulnaris, can be palpated easily within the olecranon groove.

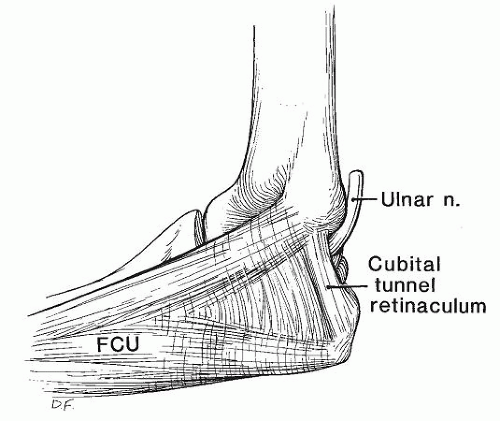

The ulnar nerve is identified at the level of the olecranon groove. A vasoloop is placed around it there. Proximal dissection is not general performed. Concentration is placed on unroofing the nerve more distally in the proximal forearm. Circumferential dissection around the ulnar nerve is not performed, which risks destabilizing the ulnar nerve. The aponeurosis is incised (Fig. 17-3). The cubital tunnel retinaculum (Fig. 17-4), which is about 4 mm wide, is released. The proximal portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris is also released.

Hemostasis is obtained with a Malis hyfrecator with the tourniquet deflated. In the rare circumstance where after the decompression, the ulnar nerve dislocates freely with elbow flexion, an anterior transposition is performed. Additional anesthesia may be required. The wound is closed.

FIGURE 17-1 The arm is draped free and placed on an arm board. Proposed incisions for an in situ decompression and an anterior transposition are demonstrated. |

FIGURE 17-2 A,B: Typical appearance of the nerve at the cubital tunnel. Note the crossing branch of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm. |

FIGURE 17-3 Compression of the nerve at this level (A) is seen clearly following release of the cubital tunnel (B). |

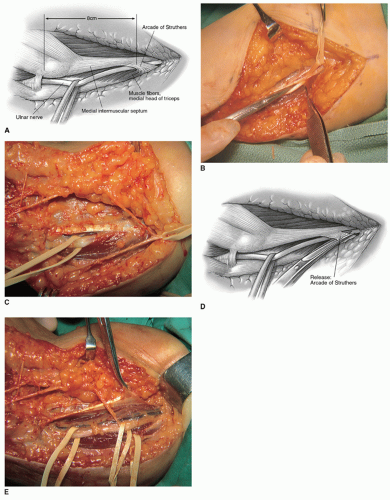

Subcutaneous Translocation The patient is usually under general anesthesia in a supine position, and a tourniquet is in place (Fig. 17-1). In a primary case, an approximately 10-12 cm long incision is made, curved posterior to the medial epicondyle, centered on the epicondyle. The medial cutaneous nerves of the arm and forearm are identified and preserved. The ulnar nerve is identified in virgin tissue proximal to the elbow and mobilized with its extrinsic vasculature. The arcade of Struthers is released when it is found 8 cm proximal to the epicondyle (Fig. 17-5A and B). An anatomical point for the presence of the arcade is in the appearance of muscle fibers of the medial head of the triceps crossing superficial to the ulnar nerve (Fig. 17-5C). The arcade is released (Fig. 17-5D and E), and the medial intermuscular septum is freed and excised (Fig. 17-6) (16).

The ulnar nerve is traced distally 6-8 cm. The cubital tunnel retinaculum is released as is the flexor carpi ulnaris aponeurosis. Just distal to the elbow joint, the articular branch is encountered, and it should be released. The motor branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum profundus branch should be preserved. These branches are mobilized microsurgically from the ulnar nerve as much as necessary to permit the anterior neural transposition. These steps permit the ulnar nerve to be easily brought forward over the epicondyle.

The nerve is transposed straight without sharp bends in either plane to prevent kinking of the ulnar nerve distal to the epicondyle by the common aponeurosis between the flexor digitorum superficialis of the ring finger and the humeral head of the flexor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 17-7) (1,9). When the nerve is translocated anteriorly in the subcutaneous plane (Fig. 17-8), it therefore runs a straight course.

During closure, the fascia of the skin flap is sutured to the antebrachial fascia just lateral to the epicondyle. This maintains the ulnar nerve anteriorly. Others prefer a fascial sling that can be utilized alternatively to stabilize the nerve in an anterior position.

Learmonth Submuscular Transposition The first half of the procedure is similar to that described in the subcutaneous technique. It differs in that the incision is longer, being 8 cm proximal and 8 cm distal to the epicondyle. Furthermore, a sterile tourniquet is utilized.

The second half of the procedure is not difficult, but it is technically demanding (10,11) with two principles in mind. First, the ulnar nerve must pass in a straight line. The longitudinal extrinsic vascular supply should be maintained during mobilization of the ulnar nerve. This should be preserved as far distally as possible by ligating the muscular communicating branches, thus keeping the extraneural vascular supply with the ulnar nerve. One can usually maintain the full length of the venae commitantes to the elbow level. The vascular variations about the elbow usually prevent full maintenance of the extrinsic vascular supply. Second, the ulnar nerve must run parallel to the median nerve in a good soft tissue bed. If the deep bed is inadequate as in severe arthrosis, or with bad articular fractures, especially of the medial half of the elbow joint, a subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve is a better choice.

In the next phase of the dissection, the lacertus fibrosus is visualized by elevating the lateral skin flap. The cutaneous nerves are preserved. The median nerve is identified deep to the lacertus. A rubber band is placed about it and the overlying fascia released. The limits of the flexor-pronator muscles are clearly in view. The median nerve is lateral to it, and the ulnar nerve is medial. A large

tonsillar hemostat is inserted just distal to the epicondyle from the lateral side deep to the flexorpronator muscles avoiding the recurrent vessels. The flexor-pronator group of muscles is severed 1 1/2 to 2 cm distal to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 17-9). The exit of the hemostat on the medial side may be troublesome, and the lateral two-thirds of the muscle is first incised and then the hemostat is repassed. Muscle bleeders are clamped and tied. Using a periosteal elevator, the flexor-pronator muscles are stripped distally. Motor branches to the flexor-pronator mass may need to be neurolysed in order to prevent undue tension on them during the muscle elevation.

tonsillar hemostat is inserted just distal to the epicondyle from the lateral side deep to the flexorpronator muscles avoiding the recurrent vessels. The flexor-pronator group of muscles is severed 1 1/2 to 2 cm distal to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 17-9). The exit of the hemostat on the medial side may be troublesome, and the lateral two-thirds of the muscle is first incised and then the hemostat is repassed. Muscle bleeders are clamped and tied. Using a periosteal elevator, the flexor-pronator muscles are stripped distally. Motor branches to the flexor-pronator mass may need to be neurolysed in order to prevent undue tension on them during the muscle elevation.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|