12

Natural Course and Prognosis of Intervertebral Disk Diseases

| Pathoanatomical Changes of the | Disk Disease over the Course of Life | 306 | |

| Intervertebral Disk | 308 | The Spontaneous Course of Acute Intervertebral | |

| Disk Disease | 307 |

The pathoanatomical changes of the intervertebral disk and the disease states that may result from them take a characteristic course. In particular, there are three processes with their own typical time curves:

degenerative changes of the intervertebral disk with advancing age

degenerative changes of the intervertebral disk with advancing age

disk disease over the course of life

disk disease over the course of life

natural course of an acute episode of disk disease.

natural course of an acute episode of disk disease.

Pathoanatomical Changes of the Intervertebral Disk

Pathoanatomical Changes of the Intervertebral Disk

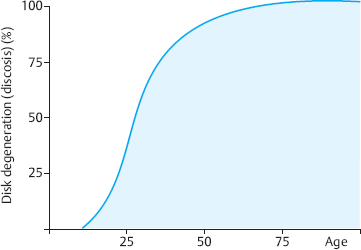

The natural course of degenerative changes in the intervertebral disk is to increase steadily from about age 20 until age 50–60, by which time disk degeneration has progressed to almost its final extent (Fig. 12.1). Plain radiographs reveal loss of disk height and spondylotic osteophyte formation (osteochondrosis, spondylosis), changes that are not considered pathological in themselves. Degenerative changes of the intervertebral disk are normally found at autopsy as well, particularly in the lower cervical and lower lumbar segments. Findings of this type from the older studies of Schmorl (1932), Coventry (1945), Hirsch and Schajowicz (1952), and Schmorl and Junghanns (1968), have been confirmed more recently by Kirkaldy-Willis (1988), Anderson (2002), Benoist (2002), Ito (2002), Greenough (2004), and Singer and Farzy (2004). These degenerative changes, like graying of the hair and wrinkling of the skin, are normal accompaniments of aging. They ultimately lead to spontaneous solidification, i.e., fibrous ankylosis of the intervertebral disks.

Discosis is normally more severe in some motion segments than in others. Impressive degenerative changes, with bridging spondylotic processes, are mainly found at C4–C7 and L4–S1. The lower segments of the thoracic spine are also more severely affected than its upper segments.

Degenerative changes of the intervertebral disk often remain asymptomatic. Boden et al. (1990) found asymptomatic disk protrusions in the MRI scans of 20% of normal individuals under 60 years of age, and 36% of individuals over 60. These findings were replicated by Jensen et al. (1994) and Boos et al. (1995).

Fig. 12.1 This graph of the prevalence of discosis (degenerative disk disease) as a function of age reveals that 100% of individuals have it by age 70–80.

Disk Disease over the Course of Life

Disk Disease over the Course of Life

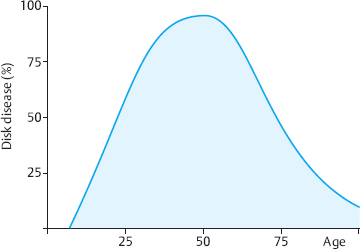

The disease curve is not parallel to the degeneration curve. Disk diseases such as lumbago, sciatica, stiff neck, and shoulder-arm syndrome occur most commonly in midlife and become steadily less frequent and less intense after the fifth decade. This frequency distribution is found both in statistical studies of conservatively managed patients (Krämer 1973, Krämer and Nentwig 1999) and in surgical statistics (McCulloch 1998, Postacchini 1999, Krämer et al. 2004). It has also been confirmed by more recent epidemiological studies (Stephens and Bell 1993, Leboeuf 1998, Bendix 2004, Kuhlmann 2004, Jarvik 2005) (Fig. 12.2).

Different clinical manifestations are produced by disk degeneration at different times of life (Table 12.1):

In younger patients, intradiscal tissue displacement leading to disk protrusion can produce clinical symptoms: the typical clinical picture is extension stiffness of the hip and thigh (cf. Chapter 11). The MRI may reveal protrusion of the posterior edge of the disk. The “board sign” is the most notable finding on physical examination, and radicular signs are usually absent. Pain usually radiates into the leg no further down than the proximal portion of the affected dermatome. Because younger patients’ disks remain closed even when they protrude, conservative management is recommended, including traction, physiotherapy exercises, and stress-reducing positioning. The course of disk disease in young individuals is slow but generally favorable, i.e., disk prolapse usually does not ensue as long as patients modify their behavior appropriately and correct treatment is provided.

In younger patients, intradiscal tissue displacement leading to disk protrusion can produce clinical symptoms: the typical clinical picture is extension stiffness of the hip and thigh (cf. Chapter 11). The MRI may reveal protrusion of the posterior edge of the disk. The “board sign” is the most notable finding on physical examination, and radicular signs are usually absent. Pain usually radiates into the leg no further down than the proximal portion of the affected dermatome. Because younger patients’ disks remain closed even when they protrude, conservative management is recommended, including traction, physiotherapy exercises, and stress-reducing positioning. The course of disk disease in young individuals is slow but generally favorable, i.e., disk prolapse usually does not ensue as long as patients modify their behavior appropriately and correct treatment is provided.

In midlife, the frequency and intensity of disk disease rise. Protrusions and prolapses, with outward displacement of the central, mobile disk tissue, exert pressure on the nerve root. The basic pathogenetic mechanism consists of two factors: a still high turgor pressure in the disk, combined with an already somewhat torn and less durable anulus fibrosus (see Chapter 4). Disk disease can be present in middle age in either the cervical or the lumbar spine.

In midlife, the frequency and intensity of disk disease rise. Protrusions and prolapses, with outward displacement of the central, mobile disk tissue, exert pressure on the nerve root. The basic pathogenetic mechanism consists of two factors: a still high turgor pressure in the disk, combined with an already somewhat torn and less durable anulus fibrosus (see Chapter 4). Disk disease can be present in middle age in either the cervical or the lumbar spine.

Comfortable rigidity of the aging spine (Kraemer 1995). In the third phase of the spontaneous pathoanatomical process of disk degeneration, the intervertebral disks develop fibrotic ankylosis. The disks show marked degenerative changes, with signs of wear and tear, but the disk tissue has dried out to such an extent that it has little tendency to become displaced.

Comfortable rigidity of the aging spine (Kraemer 1995). In the third phase of the spontaneous pathoanatomical process of disk degeneration, the intervertebral disks develop fibrotic ankylosis. The disks show marked degenerative changes, with signs of wear and tear, but the disk tissue has dried out to such an extent that it has little tendency to become displaced.

The intervertebral disks wither with age.

The intervertebral disks wither with age.

There may be an osteophytic reaction, with narrowing of the spinal canal potentially leading to the so-called spinal stenosis syndrome, but disk degeneration itself is usually asymptomatic in old age. The main feature of the structural-biomechanical constellation of asymptomatic disk degeneration in old age is dehydration of the disks with fibrotic ankylosis of the motion segments. In addition, elderly individuals are generally less physically active than they were when younger. Recent studies confirm that the spontaneous course of disk disease in old age is benign (Cinotti et al. 1998, Kirkaldy-Willis 1988, Martikainen 1998, Ferguson 1999, Anderon 2002, Greenough 2004, Nakagawa 2004). The comfortable rigidity of the aging spine in old age can still be disrupted, however, by accidental trauma or inappropriate behavior (e.g., vigorous gardening) as well as by misguided treatments such as chiropractic manipulation or mobilizing physiotherapy exercises.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree