Fascial Pain

Fascia is continuous from head to toe, surrounding every muscle, tendon, nerve, blood vessel, bone, and organ. It is interconnected in various sheaths or planes, holding structures together, giving them their characteristic shapes and support. The ability of fascia to absorb and redistribute forces makes it a compensatory organ.

Fascia is comprised of three layers, superficial, deep, and subserous. Superficial fascia is a continuous layer of connective tissue over the entire body between the skin and the deep fascia. Holding muscles and other structures in place are the connective sheets and bands of deep fascia. Lining the body cavities and viscera between deep fascia and the subserous membrane is a subserous fascia, addressed more commonly in visceral techniques. Its elastic and flexible properties afford fascia its dynamic capabilities and fluid movements. In addition, movement and warmth increase the elasticity of fascia as it stretches and moves freely to accommodate the biomechanical stresses of the body.

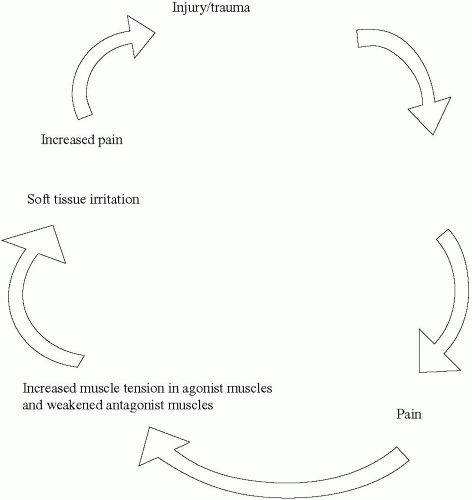

The repetitive stress and mechanical loading of tissues by athletic training cause increased strain on the fascial system. This increase in muscle tension commonly disrupts flow in the delivery of nutrients and removal of waste products in the tissues. The accumulation of waste products acts as an injurious stimulus, inducing further tissue irritation, pain, and inflammation. Up to this point, the process can be thought of as acute. Acute processes generally manifest as severe, sharp tenderness, edema, erythema, and bogginess in the soft tissues, with increased moisture and hypertonicity.

The continuation of this course results in a fibrous tissue reaction leading to a chronic process. Chronic changes are less likely to be reversible, making the soft tissue damage more permanent. Furthermore, the body experiences muscle shortening, decreasing stretch, and restricting movements. Manifestations of chronic processes are usually dull, achy, burning, ropy, cool, dry skin with fibrotic changes and slight tension.

Both acute and chronic tissue changes often present with compensation in other parts of the body. The pervasiveness and interconnectedness of fascia throughout the body create a scenario in which restriction in one part of the body will not only affect local, adjacent structures but may also affect areas distal to the site of injury. It then becomes necessary to address dysfunction in both the local area of injury as well as in distant areas.

Myofascial pain is sometimes associated with fibrositis, defined by fibrous tissue inflammation and connective tissue hyperplasia. Frequently, a hyperirritable region within a taut band of tissue with referred pain is known as a myofascial trigger point. Trigger points have a predictable distribution and are commonly found within areas of myofascial pain. The concept and principles of myofascial trigger points can be further studied in works by Janet Travell.

Because of the fascia’s integration with the neuromuscular system, many symptoms are mediated by the sympathetic nervous system. Myofascial release elicits neuroreflexive changes in the musculoskeletal system, from the skin to deep spinal joints. During myofascial release, the afferent stimulation caused by a stretch movement results in the sequential relaxation

of tight tissues by efferent inhibition, providing instant relief on many occasions.

Tight-Loose Concept (Direct-Indirect Barriers) in Myofascial Release

Tightness creates asymmetry, and looseness permits asymmetry. Three main barriers are encountered in osteopathic manipulation: the physiologic, anatomic, and restrictive (pathologic) barriers. A

restrictive barrier causes asymmetry and inhibits movement in one direction. This is a basic concept of myofascial release, and looking for three-dimensional tightness and looseness is essential. Areas of myofascial injury can vary in size, pattern, and depth (superficial to deep), and they can be tight or loose in relation to one another.

The term “end-feel” describes the sensation one feels when a mobilized joint moves into a barrier, or the end of its range of motion. Asymmetrically perceived end-feels are commonly referred to as direct and indirect barriers. Direct barriers suggest tethering and tightness, whereas indirect barriers suggest tissue laxity and looseness. Movements are easier in some directions, less so in others. End-feels that are hard and terminate abruptly occur with direct barriers, whereas indirect barriers have soft and easy-tonavigate end-feels. Restrictions involving one side of the body frequently affect the opposite side.

Tight muscles are not always sources of pain and altered neuromusculoskeletal functioning. On the other hand, loosened sites are often chronic, painful, and susceptible to injury at relatively low thresholds of stress. Tight muscles can be self-limiting or they can steady an unstable region by increasing fibrotic tissue formation.