Myeloma

Myeloma, a tumor of hematopoietic derivation, is the most common primary neoplasm of bone. Among malignancies involving the skeleton, only metastatic carcinoma is more common. There are more than 5,000 patients with myeloma documented in the Mayo Clinic files. However, this series includes only patients whose diagnosis was made with needle biopsy or open biopsy. The neoplasm is composed of plasma cells that show various degrees of differentiation. The process is usually multicentric and often involves bone marrow so diffusely that it is diagnosed most frequently on the basis of bone marrow aspiration.

Most patients with myeloma present with predominant hematologic problems, and their therapy is managed by hematologists or by oncologists and radiotherapists. The discussion in this chapter is oriented toward the problems encountered in surgical material. The complex hematologic and protein disturbances will not be considered, but some of the pertinent literature is indicated in the bibliography. Extraskeletal infiltrates of myeloma cells in a wide variety of tissues may occur in patients with multiple myeloma. Nearly 80% of the infiltrates of solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma occur in the upper air passages and oral cavity. In most cases, these are cured with local therapy, which has included electrocautery, excision, irradiation, or a combination of these. In some patients with these extramedullary plasma cell tumors, multiple myeloma develops.

Renal involvement with manifestations of renal insufficiency is an important complication of myeloma that may be the immediate cause of death. The usual histologic finding is not myelomatous infiltration but blockage of the tubules by proteinaceous casts. Much less important is the occasional development of renal amyloidosis, “metastatic” calcification of the kidneys in patients with skeletal demineralization, or pyelonephritis.

Occasionally, a single osseous focus of myeloma is associated with normal marrow and with few or none of the usual laboratory findings so characteristic of multiple myeloma. In patients with such lesions, multiple myeloma usually develops, but this occurs sometimes only after a latent period of 5 to 10 years or even longer. Some patients experience long-term “cures.” “Solitary” myeloma in bone must be differentiated from a focus of chronic osteomyelitis with abundant plasma cells. The distinction is aided by the finding of proliferation of fibroblasts and capillaries as part of the response to inflammation and the sprinkling of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and histiocytes in the latter condition. Rarely, immunohistochemical staining for monoclonal antibodies may be needed to differentiate the monoclonal growth of cells in myeloma from the polyclonal growth in osteomyelitis.

INCIDENCE

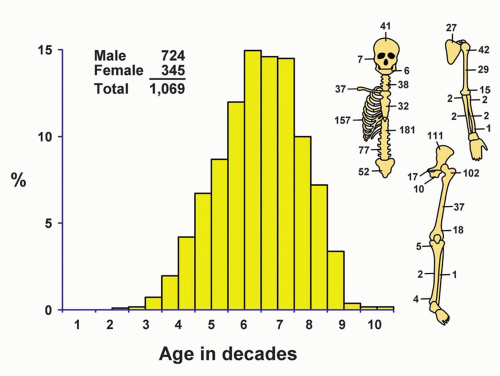

The 1,057 myelomas of bone comprise 14.9% of the malignant bone tumors in the Mayo Clinic series (Fig. 16.1). The major reasons for operation in the surgical series included the presence of an indeterminate osseous lesion, compression of the spinal cord, or pathologic fracture.

SEX

Of the 1,069 patients who underwent surgery, 67.7% were males.

AGE

The well-known rarity of myeloma in patients who are younger than 40 years is shown in the Mayo Clinic series. The youngest patient was a 16-year-old boy with a lesion of the lumbar vertebra. Only 7.2% of the patients in the surgical series were in the first four decades of life. The largest concentration was in the sixth and seventh decades of life.

LOCALIZATION

The bones that contain hematopoietic marrow in adults harbor most of the recognizable myeloma nodules. Although these data are selective because they are based on surgical cases only, the distribution shown is similar to that observed at autopsy, except that the skull is usually involved by the time that myeloma has caused the patient’s death. In a review of the cases of 46 patients from the Mayo Clinic files who had “solitary” plasmacytoma of bone, Frassica and coauthors found that 54% of the lesions involved the vertebral column. In a few tumors listed as maxillary, it was difficult to be certain that the neoplasm began in bone.

SYMPTOMS

Increasing pain is the most frequent complaint of patients with myeloma, and the pain is most often centered in the lumbar or thoracic spinal region. On average, the pain is of less than 6 months’ duration before the patient seeks medical attention, but sometimes it has been present for several years. Nearly every patient with myeloma has weakness and loss of weight during the disease. Pathologic fracture, with abrupt onset of symptoms, is common, and most such fractures involve the vertebral column. Neurologic symptoms, usually from disease of the spinal cord or nerve roots secondary to pathologic fracture or extraosseous extension of the neoplastic tissue, are frequently observed. Peripheral neuropathy associated especially with the osteosclerotic form of myeloma is increasingly being recognized. There were 54 patients with osteosclerotic myeloma, at least 36 of whom had peripheral neuropathy. Not all patients with osteosclerotic myeloma present with peripheral neuropathy. Not all patients with peripheral neuropathy and associated myeloma have the osteosclerotic form. Rarely, peripheral neuropathy may be associated with classic myeloma. The etiology of the peripheral neuropathy in these two kinds of myeloma probably is different. Complaints referable to renal involvement may be encountered. Less common symptoms include palpable tumor, hemorrhagic tendency, anemia, and fever. Rarely, a patient with myeloma may present with a hypercalcemic crisis.

In rare instances, other neoplasms coexist with myeloma, and myeloma is occasionally secondary. One patient in the Mayo Clinic series developed myeloma of the proximal tibia after years of well-recognized systemic mastocytosis. A biopsy specimen from the proximal tibia showed both mastocytosis and an anaplastic myeloma. One patient had myeloma associated with an enchondroma, producing the radiographic appearance of dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma.

PHYSICAL AND LABORATORY FINDINGS

Physical findings may reflect secondary changes resulting from generalized malignant disease with replacement of bone marrow. Local pain or tenderness, with

or without palpable tumor, and neurologic dysfunction may be elicited.

or without palpable tumor, and neurologic dysfunction may be elicited.

Smears of peripheral blood often show excessive rouleau formation, and it has been reported that myeloma cells are found in 70% of the patients. Rarely, plasma cell leukemia develops. Generally, there is moderate to severe anemia. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is usually rapid. Hypercalcemia occurs in 20% to 50% of patients. Eventually, Bence Jones proteinuria can be found in more than half of the patients. Evidence of renal insufficiency or amyloidosis, which may be generalized, sometimes develops. Levels of serum alkaline phosphatase are rarely elevated.

Elevation of various globulin fractions on electrophoretic studies of serum and urinary proteins provide critical diagnostic inflammation. In a study of 869 patients, Kyle found skeletal radiographic abnormalities in 79%. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a spike in 76%, hypogammaglobulinemia in 9%, and minor or no abnormalities in 15%; a globulin spike was seen in 75% of the urinary electrophoretic patterns. Serum immunoelectrophoresis revealed only a monoclonal heavy chain in 83% and a monoclonal light chain in 8% (Bence Jones proteinemia). Amyloidosis was found in 7% of the patients. There is an interrelationship among amyloidosis, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and myeloma. The complexities of these protein studies were elaborated by Osserman and Takatsuki in 1963.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

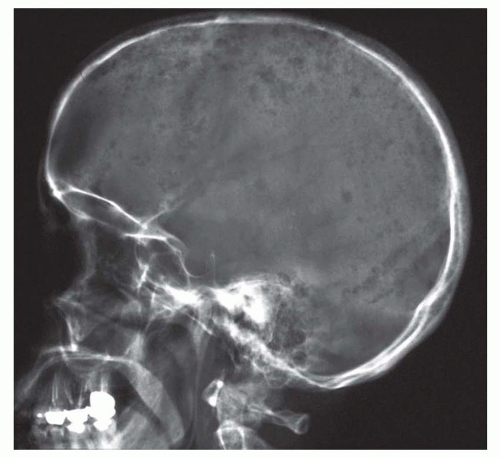

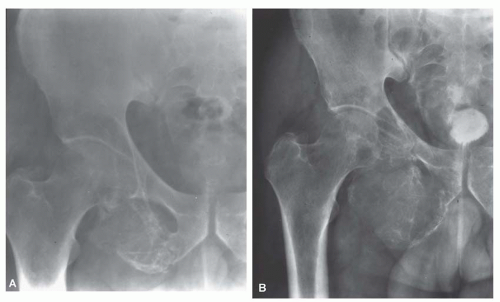

The radiographic features result from replacement of osseous structures by the myelomatous masses. The first and most extensive changes usually occur in the ribs, vertebrae, skull, and pelvis. Classically, there are “punched-out” areas of bone destruction that vary up to 5 cm in greatest dimension and have no surrounding zone of sclerosis (Figs. 16.2 & 16.3). Expansion of the affected bones may produce a “ballooned-out” appearance, especially in the ribs. Variable osteoporosis is common, and pathologic fracture, especially of vertebrae, is often seen. From 12% to 25% of patients with myeloma have no discernible foci of bone destruction. On close scrutiny, some of these patients are found to have diffuse demineralization of portions of the skeleton. Computed tomograms and magnetic resonance imaging studies may show small, discrete lesions when plain radiographs are negative or show only diffuse osteoporosis. There is some variability in the appearance of multiple myeloma on magnetic resonance images because the disease does not involve the marrow in a homogeneous fashion. In addition, the magnetic resonance appearance of the marrow depends on the extent of fatty replacement, which is variable, particularly with age. Metastatic carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, and hyperparathyroidism can produce bone lesions that may simulate myeloma. The lesions of metastatic carcinoma and malignant lymphoma are usually positive on bone scans, whereas the lesions of myeloma usually are not. “Solitary” myeloma lesions of bone are classically lytic, and they too may

expand the bone (Figs. 16.4 & 16.5). Pugh has stated that sclerosing areas on radiographs of patients with myeloma are usually due to some process other than myeloma. However, osteosclerotic myelomas, especially those associated with peripheral neuropathy, are being diagnosed more frequently. The lesions may be solitary or multiple. The sclerosis may be in the form of a peripheral rind around a lytic focus or uniformly sclerotic lesions that simulate the appearance of blastic metastases (Fig. 16.6).

expand the bone (Figs. 16.4 & 16.5). Pugh has stated that sclerosing areas on radiographs of patients with myeloma are usually due to some process other than myeloma. However, osteosclerotic myelomas, especially those associated with peripheral neuropathy, are being diagnosed more frequently. The lesions may be solitary or multiple. The sclerosis may be in the form of a peripheral rind around a lytic focus or uniformly sclerotic lesions that simulate the appearance of blastic metastases (Fig. 16.6).

Figure 16.2. Multiple myeloma. Radiograph of the skull shows multiple discrete osteolytic calcarial lesions that are the hallmark of multiple myeloma. |

Figure 16.3. Multiple myeloma involving the proximal femur. The tumor is a purely lytic lesion that erodes the bone. |

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|