CHAPTER 10 Musculoskeletal assessment

Section 10A Orthopaedic assessment of the lower limb

Introduction

Movement of the lower limb involves interaction between the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. The function of both systems can be compromised by vascular pathology. This chapter concentrates on the orthopaedic assessment of the musculoskeletal system. The assessment of the vascular system is covered in Chapter 6 and the neurological basis of movement and assessment of the nervous system are covered in Chapter 7. As the healthcare practitioner becomes competent, experienced and confident, essential components of these three systems will be evaluated seamlessly during the patient evaluation. Although reference is made to the weightbearing examination during this chapter, this subject, including gait analysis, is covered in greater detail in section 10B (functional assessment).

The assessment process begins with a detailed history of the patient’s complaint. Subsequent examination of the limbs is based on an approach following the methodology outlined by McRae (2004):

Qualitative, semiquantitative and quantitative measurement techniques are used. The practitioner should be aware of the likely errors that can ensue from such measurements and take these into consideration when interpreting and analysing data from the assessment (see Ch. 4).

Terms of reference

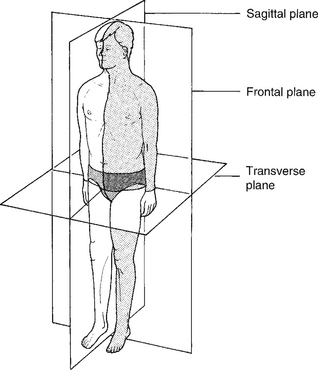

The body is divided into three cardinal planes (Fig. 10A.1):

These planes form the reference points from which are described:

The position of a part of the body

The cardinal body planes are used as reference points to describe positions within the body:

• Anterior (to the front of) and posterior (to the rear of) describe positions in the frontal plane, e.g. the patella, or knee cap, lies anterior to the main weightbearing part of the knee joint (tibio-femoral).

• Distal (away from the centre) and proximal (towards the centre) describe positions in the transverse plane, e.g. the interphalangeal joints of the foot (IPJs) lie distal to the metatarsophalangeal joints (MTPJs) of the foot.

• Medial (towards the midline of the body) and lateral (away from the midline of the body) describe positions in the sagittal plane, e.g. the navicular lies on the medial side of the foot and the cuboid on the lateral side.

• In the foot, dorsal is used to refer to the top of the foot and plantar to the sole of the foot. The equivalents in the hand are dorsal and palmar.

Joint motion

Sagittal plane

Motion in the sagittal plane produces extension and flexion. The terms used to describe sagittal plane motion in the foot are slightly different from those used to describe such motion at the hip and knee (extension and flexion).

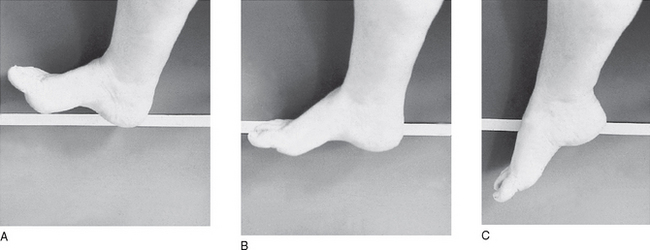

At the ankle (Fig. 10A.2), the midtarsal joints (MTJs), the MTPJs and the IPJs, sagittal plane motion is termed dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. Dorsiflexion denotes a raising of the whole or part of the foot towards the leg, whereas plantarflexion denotes the movement of the dorsal aspect of the foot away from the leg.

Frontal (coronal) plane

Abduction is when the distal segment moves away from the midline of the body and adduction when it moves towards the midline. For example, in order to do the ‘splits’, gymnasts must abduct their legs. Inversion of the foot is when the plantar aspect of the foot is tilted so as to move towards the midline of the body. Eversion is when the plantar aspect of the foot is tilted so as to face away from the midline of the body (Fig. 10A.3).

Transverse plane

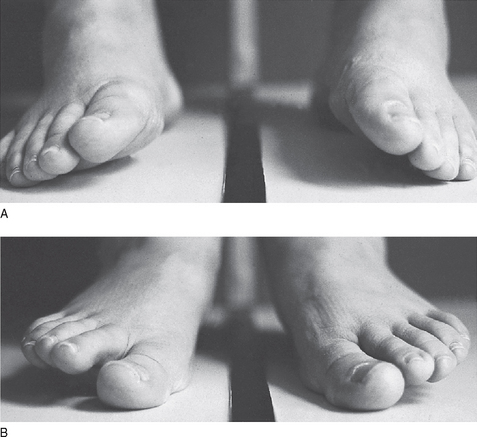

Internal rotation occurs when the anterior surface of the distal segment rotates medially in relation to the proximal segment and external rotation when the opposite occurs – the anterior surface of the distal segment moves laterally in relation to the proximal segment (Fig. 10A.4).

• Abduction of the foot is when the distal part of the foot moves away from the midline of the body

• Adduction when the distal part of the foot moves towards the midline of the body (Fig. 10A.4).

Triplanar motion

The position of the joint axis together with the shape of the articulating surfaces can result in motion in more than one plane for a joint or combination of joints acting together.

• Pronation is the collective term for dorsiflexion, eversion and abduction.

• Supination is the collective term for plantarflexion, inversion and adduction.

For example, in the foot triplanar motion occurs at the subtalar and midtarsal joints.

Position of a joint

To describe the position of a joint the suffix ‘-ed’ is used:

• Sagittal plane – extended and flexed (thigh and leg); dorsiflexed and plantarflexed (foot)

• Transverse plane – internally and externally rotated (thigh and leg); adducted and abducted (foot)

• Frontal plane – abducted and adducted (thigh and leg); inverted and everted (foot)

Deformity of a part of the body

The term ‘deformity’ is used to describe an abnormal position adopted by a part of the body.

Terms used to denote deformity often have the suffix -us:

• Sagittal plane – equinus is when the foot or part of the foot is plantarflexed, e.g. ankle equinus, and extensus is when the foot or part of the foot is dorsiflexed, e.g. hallux extensus. Calcaneus is used to describe the calcaneus when it is in fixed dorsiflexion, e.g. talipes calcaneovalgus.

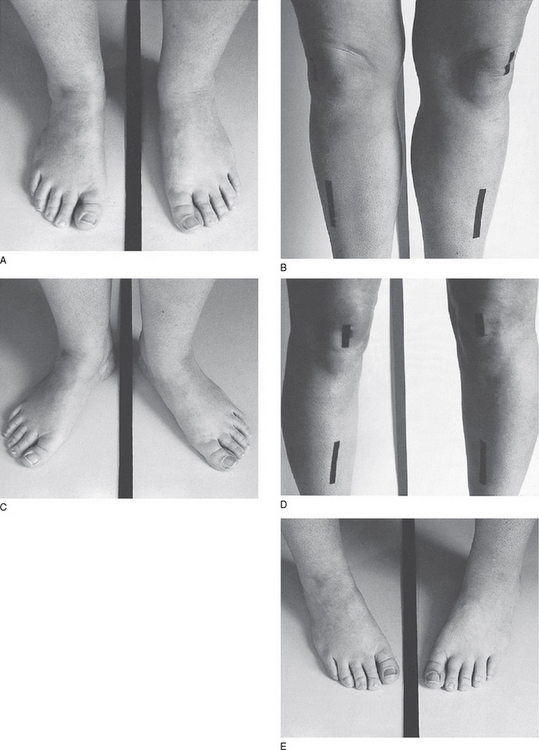

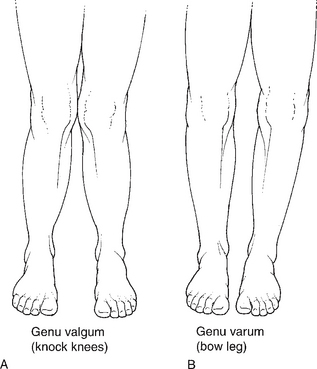

• Frontal plane – varus and valgus (Fig. 10A.5).

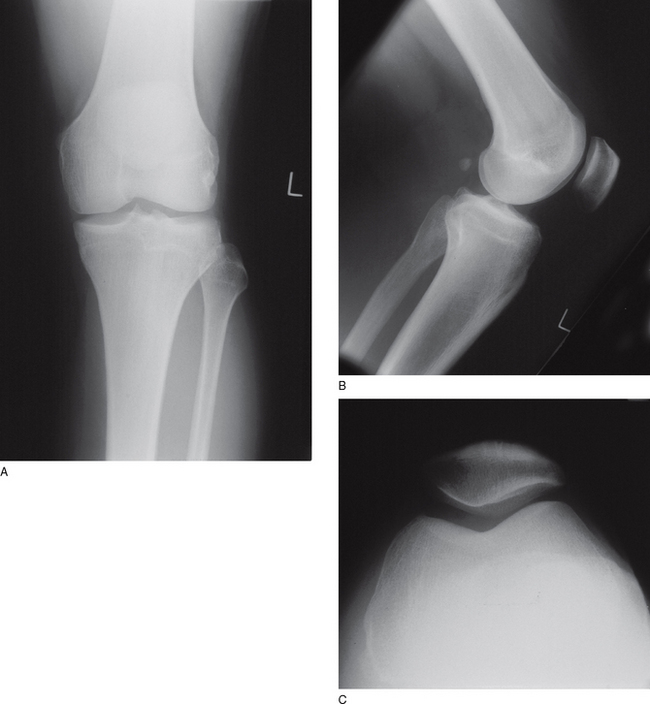

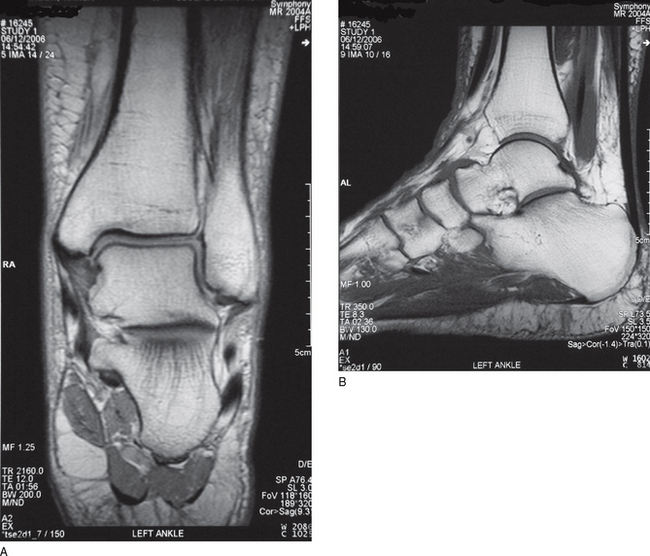

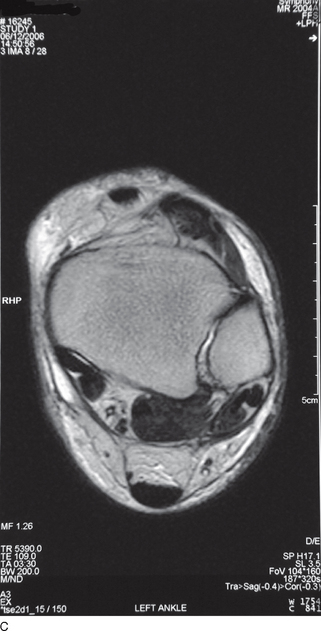

To reinforce the importance of understanding these terms, Figure 10A.6 illustrates the three planes of a knee as seen on a plain radiograph and Figure 10A.7 illustrates the three planes of the ankle and hindfoot as seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Why is an orthopaedic assessment indicated?

Normal lower limb function should be free of pain and energy efficient. The main purpose of the orthopaedic assessment is to identify whether the system is functioning within the boundaries of ‘normality’. Normal function can be affected by many factors (Box 10A.1). It should be remembered that orthopaedic lower limb problems are not always isolated in origin. They may result from referred pain from a proximal source or can be part of a systemic disorder, e.g. a neuromuscular disease. It is therefore important that the lower limbs are not examined in isolation and that observation and examination of other parts of the body are undertaken where indicated.

Box 10A.1 Factors that can affect normal function

• Hereditary/congenital problems, e.g. Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, talipes equinovarus, developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

• Acute/chronic injury causing pain, e.g. slipped capital femoral epiphysis, ankle sprain

• Abnormal alignment secondary to trauma, e.g. femoral/tibial/epiphyseal fracture

• Abnormal alignment (developmental), e.g. internal femoral torsion, genu valgum

• Infections, e.g. tuberculosis

• Neurological disorders, e.g. cerebrovascular accident

• Muscle disorders, e.g. Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy

• Neoplasia, e.g. osteosarcoma

• Systemic disease, e.g. autoimmune (rheumatoid arthritis), bone disease (Paget’s disease)

• Degenerative processes, e.g. osteoarthritis

• Joint hypermobility, e.g. Marfan’s syndrome

• Osteochondroses, e.g. Perthes’ disease

• Psychological factors, e.g. attention seeking

In summary the purpose of an orthopaedic lower limb assessment is to:

• establish the main complaint(s), e.g. pain, stiffness, tenderness, numbness, weakness, crepitus

• identify the site of the primary problem, e.g. foot, leg, knee, hip, and try to relate to underlying structures

• identify any secondary problems and relate them to the primary problem, e.g. lesion patterns, pronation due to leg-length discrepancy

• identify the cause of the problem, e.g. abnormal alignment

• establish how the problem evolved

• identify any movement/activity that produces/exacerbates symptoms

• identify movement/activity that relieves symptoms

• establish any differential diagnoses

• utilise the data from the assessment to produce an effective management plan

• utilise the data from the assessment to monitor the progress of the condition.

The assessment process

The sequence of assessment of the above varies among practitioners. There is no one correct sequence; practitioners should adopt the sequence and approach they feel most comfortable with. However, it is essential that a systematic approach is adopted to ensure vital pieces of data are not omitted. For complete assessment, the examination should involve the following three important sections:

1. Non-weightbearing. This will focus on the assessment of joints and muscles.

2. Gait analysis. This will focus on the position and alignment of the body and foot–ground contact during dynamic weightbearing.

3. Static weightbearing. This will focus on the position and alignment of the body and the relationship of the foot to the ground during stance.

Areas 2 and 3 are covered in greater detail in section 10B.

General assessment guidelines

• Always observe and functionally assess the joints bilaterally.

• It is valuable to obtain an overview of both limbs, particularly if the onset of the problem is insidious, the pain is diffuse and nonspecific or if during testing a number of joints seem to be implicated.

• Where only one limb is affected, it is often helpful to start with the unaffected limb first, then repeat the test on the affected limb. Compare ranges of motion, end feel (the sensation the examiner feels when they push the joint being examined to the end of its range of motion) and muscular strength.

• It is helpful to arrange your testing so that the most painful test is last. This ensures that the condition will not be aggravated by your testing procedure or make the patient apprehensive.

The process of assessment follows a standard format:

Examination of joint movement

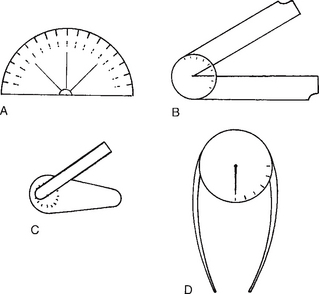

ROM is the amount of motion at a joint and is usually measured in degrees. The ROM at a joint can be compared with the expected ROM for that joint, e.g. if only 20° of motion occurs at the first MTPJ when the expected norm is 70° (28% of the normal ROM) it can be concluded that the ability of this joint to carry out normal function is impaired (hallux limitus). Often a guesstimate of the amount of joint motion is made from observation. Protractors, tractographs and goniometers can be used to quantify joint motion (Fig. 10A.8).

Figure 10A.8 Devices used to measure joints. A Protractor. B Tractograph. C Finger goniometer. D Gravity goniometer.

A joint may show normal ROM but the direction of the motion may be abnormal. It is, therefore, important to note the direction as well as the range. For example, the total ROM of transverse plane rotation at the hip is 90°; 45° internal rotation and 45° external rotation. If the ROM is 90° but there is 70° of external rotation and 20° of internal rotation then the ROM would be normal but the direction of the motion would be abnormal. Normal joint motion should occur without crepitus, pain or resistance (quality of motion). The ROM and direction of motion of a joint, e.g. hip, should be the same for both limbs (symmetry of motion). The presence of asymmetry of motion should always be noted.

Muscle assessment

Muscles allow active motion at joints. They should be tested for:

Strength

• 1 = a flicker from muscle fasciculi

• 2 = slight movement with gravitational effects removed

• 3 = muscle can move part against gravity

• 4 = muscle can move part against gravity + resistance

Arranging further investigations

Usually the information obtained from a detailed history and assessment is sufficient to arrive at a diagnosis. Occasionally, specialist investigations may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis or to consider other options. A number of possibilities are available including: specialist imaging techniques and haematological, biochemical and nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG). In addition, histological examination of specimens, video/treadmill gait analysis or computerised analysis/forceplate analysis may be indicated.

Non-weightbearing examination

Examination of the hip

• depth of the acetabulum, accentuated by the fibrocartilaginous labrum

• strong capsule, reinforced by capsular ligaments

Preparation for the hip examination

A proper hip examination requires both space and exposure:

• Adequate clinic space is required to allow the patient to stand and be observed standing from all positions and to walk freely.

• The examination couch should ideally not be placed against a wall. The examiner should be free to examine the patient from both sides and be allowed unencumbered assessment of parameters such as hip abduction.

• The patient should be adequately exposed. Ideally, they should be undressed down to shorts or suitable underwear. Both the hip and spinal areas should be exposed to assess linked mobility and posture.

Patient standing

The patient should be observed standing with the spine and lower limbs exposed.

Observe the patient from all positions and look for evidence of the following:

• Wasting: Wasting particularly of the thigh and gluteal (buttock) musculature may indicate long-standing hip pathology, such as arthritis, infection and congenital disorders.

• Scars: Has the patient had previous surgery or sustained any traumatic injury? A pitted sinus may indicate previous infection, e.g. tuberculosis.

• Exaggerated lumber lordosis: This is observed from the side and, if present, may indicate a fixed flexion deformity of the hip joint.

• Limb attitude: The position of both limbs will indicate any rotational or frontal plane (abduction/adduction) gross deformities.

• Evidence of limb-length inequality: See section on limb-length inequality.

Trendelenburg’s test

• Weak abductors, e.g. in poliomyelitis, muscular dystrophies, post-surgical nerve damage

• Painful arthritic hip joint, which both inhibits gluteal activity and increases friction within the joint opposing abductor activity

• Congenital disorders, e.g. developmental dysplasia of the hip and coxa vara

• Previous injury to the proximal femur, reducing the efficiency of the gluteal system.

Palpation

• anterior groin for crepitus, swelling and tenderness – remember the other causes of groin pain including herniae, varicose veins and swollen lymph nodes

• lateral structures – including the greater trochanter and gluteal area for evidence of trochanteric bursal pathology

• iliac tuberosity for proximal hamstring pathology

• piriformis tenderness – rarely related to sciatic nerve compression.

Assessment of hip joint mobility

Hip joint mobility should be assessed in three planes:

Frontal plane movement

• Each limb in turn can be raised and brought across the midline over the contralateral limb.

• The contralateral limb can be raised by an assistant, allowing the limb being examined to be moved in a more pure frontal plane.

• With the contralateral limb held in an abducted position, e.g. flexed at the knee over the side of the couch, move the limb being examined into the space vacated by the other limb.

Transverse plane movement

With the patient supine, rotation can be assessed with the hips and knees extended, i.e. the legs straight. Observe the patient from the foot of the bed and assess rotation in each limb simultaneously. Hold each heel in the palm of your hands and first externally rotate and then internally rotate each limb. In this position, rotation is derived from the hip, unless there is any knee instability. It is useful to observe the movement of the patellae as a gauge of the amount of rotation from the hip. The alternative method with the patient supine is to flex to 90° the hip and knee joints. This may be difficult if hip flexion is painful and restricted. The hip is moved both internally and externally and the angle is measured by comparing the position of the shin with respect to the midline.

In health, 45° of comfortable internal and external rotation is possible. In certain conditions, e.g. unilateral excessive femoral anteversion, the total rotational arc may be the same in both hips, but with a skew in one rotational direction in one hip compared to the other. Females tend to show more internal rotation than males (Svenningsen et al 1990). The range of transverse plane motion at the hip decreases with age and most hip pathologies.

Knee examination

The knee joint is a complex synovial joint and should be considered as having three parts:

History

A thorough assessment of a knee joint problem requires information about several key issues.

Background information

Knowledge of many background features is important:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree