Chapter 3 Modifiers of Complementary Therapy: Legal, Ethical, and Cultural Issues

Several books have been written about legal and ethical issues relevant to medicine, allied health, and nursing.1–6 Terms such as negligence, malpractice, abandonment, and informed consent are defined, and examples within the practice of allopathic medicine are provided and examined.1–5 A discussion of ethics or bioethics, a term used to describe ethics that concern clients and health care, often includes issues inextricably linked with the law and legislation, such as withdrawal of life support, assisted suicide, and fertilization/reproduction.3,5–7 Many textbooks written about culture and health care are primers on the health traditions of different ethnic groups and how their customs and culture influence their view of illness and use of health care services.8–12 Understanding and accepting these health care traditions is thought to be the first step to provide culturally competent health care within a traditional or allopathic health care system.10–12 Books written about legal, ethical, and cultural issues relevant to the practice of alternative medical systems such as homeopathy and traditional Chinese medicine or the integration of complementary therapies into a traditional medical model are less available than texts written for the practice of allopathic medicine and focus primarily on the legal aspects of complementary care.13–17 This chapter will provide definitions of relevant legal and ethical terms and their relationship to CAM and offer a discussion of how these issues might be integrated with concerns about cultural issues and cultural competence.

LEGAL ISSUES

Law is the foundation of rules, regulations, and statutes that govern the behaviors of individuals and members of institutions and their interactions with others. The rules of law are the formal rules of conduct that provide the basis for conflict resolution between individuals, corporations, the state, and other organizations. The law applies to all people, regardless of education, position, income, or personal philosophy. Therapists, seamstresses, physicians, and actors must obey the laws of their jurisdictions or face some form of punishment, such as fines or imprisonment. In general, the intention of law is to resolve conflict peacefully and protect citizens’ health, safety, and welfare.3 Lawsuits against health care providers can be classified as criminal or civil.

Criminal law is concerned with violations against society’s criminal codes or statutes.3 Practice without a license, falsification of records, and fraud are examples of criminal charges that can be waged against a licensed health care provider by the state or federal government. Defendants are found either guilty or not guilty of breaking the law. Individuals found guilty in a criminal court often face imprisonment as punishment.

Civil law pertains to actions that have caused harm to a person or a person’s property. An individual or an entity other than the government wages civil suits. Most civil violations in health care involve malpractice, although health care providers have been charged with other civil wrongs or “tort,” such as assault, battery, and breach of confidentiality. In civil cases, the defendant is found either liable or not liable for the harm realized by the plaintiff. Health care providers found liable for harm typically incur monetary damages as their punishment.1

Civil malpractice liability can occur when care or services are determined to be substandard or fail to meet minimally acceptable practice standards and/or have violated legal or ethical standards.1 Professional negligence, breach of a contractual promise made to a client, and intentional conduct that resulted in client harm are examples of actions that can result in malpractice liability claims. Health care professionals also may be found at least partially liable for client injuries if they occurred by poorly maintained or faulty equipment or if the treatment or practice environment was deemed unsafe.

The practice of CAM raises both criminal and civil legal issues. Medical licensing laws, enacted to protect the public from unqualified physicians, identify the activities and procedures included in the practice of medicine and the criteria that individuals must meet to legally perform those activities and procedures. Licensure provides the highest level of assurance to the public that providers have the authority and capability to practice within a legally sanctioned boundary.13 Like physicians, physical therapists are licensed in all 50 states and must adhere to their respective state medical or physical therapy practice acts. Although the definition of “practice of medicine” or “practice of physical therapy” may vary among states, all state statutes include statements about a professional scope of practice, including the provision of services that can be rendered legally.

Although the National Center for Comple-mentary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) has defined CAM as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine,”18 no single definition of CAM exists within the law.13 Nevertheless, nearly 30 states have added various definitions into law that allow physicians to use and practice various forms of complementary, alternative, and traditional cultural medicine. In general, laws that govern CAM are the same laws that govern medicine and health care. Therefore physicians and licensed health care providers who integrate CAM into their conventional practices should be aware of how the law may be applied to issues of scope of practice, licensure, and malpractice when procedures and interventions are considered to be complementary or alternative.

Nonmedical doctors who practice CAM may be regulated in different ways depending on the CAM approach or the state in which the therapy is being offered. Chiropractors, for example, are licensed in all 50 states, but only Nevada, Arizona, and Connecticut license homeopaths, who are also physicians. The practice of naturopathy is illegal in Tennessee and South Carolina, yet 15 other states license naturopaths. Laws governing massage therapy vary across states and may or may not include different approaches of manual body-based therapy, such as Rolfing (see Chapter 19) and Trager Bodywork.19

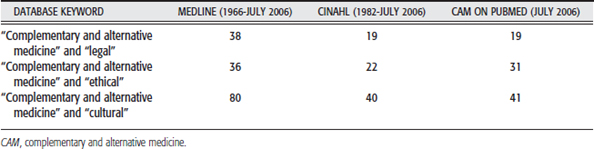

To stay current with changing regulations and interpretations of complementary treatment that is integrated into a traditional medical plan of care such as acupuncture, or as a distinct profession, as in the case of chiropractics, therapists should search state practice laws and the literature. Table 3-1 represents the results of a literature search when the key term complementary and alternative medicine was combined with legal, ethical, and cultural, respectively. A review of this literature highlights current and important considerations for practitioners who practice CAM exclusively and for health care professionals who integrate CAM approaches and therapies into a practice of traditional medicine and rehabilitation.

All states have broad definitions of medicine and prohibit the practice of medicine without a license. In states where no separate licensure or registration exists for providers of CAM such as herbalists and traditional naturopaths, CAM practitioners may be vulnerable to criminal prosecution for the practice of medicine without a license.20 Health care providers who are licensed by state legislatures such as physicians, nurses, chiropractors, and physical therapists and who add CAM to the array of interventions they offer clients may be vulnerable to disciplinary action by professional boards for practicing outside the accepted standards of care and/or risk suspension of their licenses depending on the interpretations of their respective practice acts. Several states, however, have enacted laws that permit the practice of CAM by medical doctors thereby reducing their risk of liability for practicing outside their scope of practice. One state, Florida, permits all licensed health care professionals to practice CAM within the defined parameters of the law. Knowledge of changes to laws governing the practice of medicine and health care in a therapist’s jurisdiction is important for managing practice and related risk.

Many CAM providers not otherwise licensed as health care providers argue that the practice of CAM falls outside the definition of medicine and the biomedical model of health care because interventions are offered to promote health and healing rather than cure a disease. They suggest that massage therapists, Reiki masters (see Chapter 17), and Rolfers (see Chapter 19) provide services that fall outside the scope of medical practice. Nevertheless, practitioners prosecuted for offering health care services interpreted as the “practice of medicine” include midwives, faith healers, nutritionists, and those who provide ear piercings.15 Similar to the changes in state laws that have affected licensed health care professionals, several states have enacted laws that affect the practice of unlicensed CAM practitioners. For example, under the Consumer Freedom of Choice laws that have been passed in a few states, unlicensed practitioners can practice CAM as long as they provide consumers with proper disclosure and avoid prohibited acts spelled out in the exemption laws. In addition, some practitioner groups have sought state registration or licensure to be exempt from criminal violations and to obtain a designated scope of practice consistent with their training and credentials. Knowing a state’s medical practice act, all other practice acts, and scopes of practice relative to complementary approaches and therapies is an important step toward understanding the risks and liability that may exist in provision of CAM.

Malpractice

Standard medical dictionary or glossary definitions of “malpractice” are somewhat limited. Taber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary defines malpractice as “incorrect or negligent treatment of a client by persons responsible for health care,”21 whereas Aiken3 describes malpractice as a “dereliction of professional duty through negligence, ignorance or criminal intent.” More useful than these definitions, however, is an appreciation of what conditions or situations can be used as a basis for liability and malpractice. Scott1 suggests that health care providers can be held liable for client injury if any of the following conditions exist:

When this definition of malpractice is applied to CAM, Cohen20 and Green22 suggest that liability may exist in cases of substandard care and in situations in which the health care professional fails to conform to a standard of care and injury occurs. The definition of standards of care has developed over time through scientific inquiry, dissemination of research findings, and the interaction of physicians and health care leaders. Taught in medical schools, standard medical care includes practices widely accepted across medically based disciplines. Historically, CAM had not been taught in medical schools and was considered care that was not used in U.S. hospitals.23 Based on these definitions, health care professionals who provide complementary or alternative interventions and do not conform to a standard of care may increase their risk for malpractice liability.

Today, however, instruction in CAM and integrative medicine is finding its way into U.S. medical schools,24 and hospitals are establishing centers of complementary and integrative health care25,26 in part because of client demands and in part because of a surge in CAM research.26–28 A standard of care for CAM is far less developed than the standards of conventional medicine, so courts may assess whether the particular standard of care has been met and whether the CAM therapy or approach contributed to client harm based on medical consensus of the therapy’s safety and efficacy.23 Just as basic science and outcome-based clinical research has challenged or supported standards of care over time, the same is expected in CAM. Cohen15 suggests that once research in alternative medical systems and complementary therapies has demonstrated safety and efficacy, CAM, or at least specific CAM therapies or approaches, should gain general medical acceptance and fall within a standard of care. This acceptance would decrease the risk of liability for health care providers who practice CAM either by integration of a particular CAM therapy or approach into their practice or by referral of clients to CAM practitioners.31

Despite the public’s huge interest and use of CAM,23 research in this area is in its infancy. Some interventions such as acupuncture have a robust literature and is now a recommended intervention for several conditions, including postoperative nausea and vomiting.30 Other interventions such as polarity therapy and colon therapy have not been investigated extensively for safety and efficacy. As CAM research continues and specific CAM therapies change position on the spectrum of risk and effectiveness, standards of care will change accordingly. Physicians and other licensed health care providers who seek to appraise their potential liability risk for incorporation of CAM into a standard of care will find suggestions from Cohen and Eisenberg29 in Figure 3-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree