Rheumatoid Vasculitis

- Rheumatoid vasculitis usually occurs in patients with severe, long-standing, nodular, destructive rheumatoid arthritis, especially when the joint disease is “burnt out.”

- Palpable purpura, cutaneous ulcers (particularly in the malleolar region), digital infarctions, and peripheral sensory neuropathy are common manifestations.

- Tissue biopsy helps establish the diagnosis of rheumatoid vasculitis. Nerve conduction studies can identify involved nerves for biopsy. Muscle biopsies should be performed simultaneously with nerve biopsies to increase the diagnostic yield of the procedure.

Rheumatoid vasculitis (RV) is a medium-vessel vasculitis that occurs in patients with “burnt-out” but previously severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The typical patient has long-standing RA characterized by rheumatoid nodules, destructive joint disease, and high titers of rheumatoid factor. The diagnosis of RV should be considered in any patient with RA in whom new constitutional symptoms, skin ulcerations, serositis, digital ischemia, or symptoms of sensory or motor nerve dysfunction develop. RV resembles polyarteritis nodosa because it leads to multiorgan dysfunction in the skin, peripheral nerves, gastrointestinal tract, and other organs. Manifestations of RV, which resemble those of polyarteritis nodosa, include cutaneous ulcerations, digital ischemia, mononeuritis multiplex, and mesenteric vasculitis (see Chapter 35).

Immune complex deposition and antibody-mediated destruction of endothelial cells both appear to contribute to RV. Certain HLA-DR4 alleles that predispose patients to severe RA may also heighten patients’ susceptibility to RV. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of RV and has a synergistic interaction in this regard with antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP antibodies). However, the inciting events leading to the development of RV among patients with previously destructive arthritis are not known. Factors in addition to vasculitis (eg, diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and hypertension) likely play an important adjunctive role in promoting vascular occlusion, but the central issue in RV is necrotizing inflammation of blood vessels.

Dermatologic findings, the most common manifestation of RV, may include palpable purpura, cutaneous ulcers (particularly in the malleolar region), and digital infarctions (Figure 42–1).

A peripheral sensory neuropathy is a common manifestation of RV. A mixed motor-sensory neuropathy or mononeuritis multiplex may also be seen. Central nervous system manifestations (such as strokes, seizures, and cranial nerve palsies) are considerably less common.

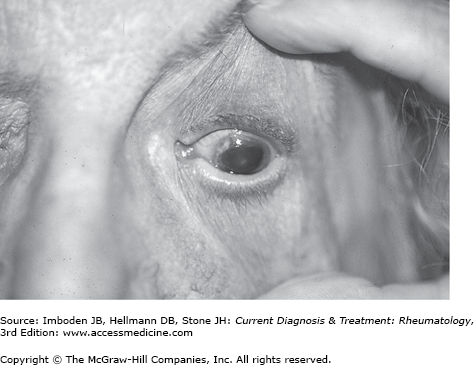

Retinal vasculitis as a manifestation of RV is common but frequently asymptomatic. Necrotizing scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis (Figure 42–2) pose threats to vision and require aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.

Pericarditis and pleuritis may occur in association with RV. Other cardiopulmonary manifestations of RV are unusual.

Most laboratory abnormalities in RV such as elevations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate are nonspecific and merely reflect the presence of an inflammatory state. Hypocomplementemia, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), atypical antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) (by immunofluorescence testing but not enzyme immunoassay; see Chapter 32), and anti-endothelial cell antibodies are all detected more frequently in patients with RV than in those with RA alone. All of these tests, however, are nonspecific.

The presence of bony erosions is a risk factor for the development of RV, but plain radiographs and other imaging studies have no consistent role in the evaluation of this disorder.

Because the treatment implications for RV are so severe, the diagnosis must be established by tissue biopsy whenever possible. Deep skin biopsies (full-thickness biopsies that include some subcutaneous fat) taken from the edge of ulcers are very useful in detecting the presence of medium-vessel vasculitis. Nerve conduction studies help identify involved nerves for biopsy. Muscle biopsies (eg, of the gastrocnemius muscle) should be performed simultaneously with nerve biopsies.

Patients with erosive RA are at increased risk for infections. When patients with RA seek medical attention for the new onset of nonspecific systemic complaints, the possibility of infection must be considered first. Cholesterol emboli may cause digital ischemia and a host of other signs and symptoms that mimic vasculitis. Diabetes mellitus is another major cause of mononeuritis multiplex, but multiple mononeuropathies occurring over a short period of time are unusual in that condition. Many clinical features of RV mimic those of polyarteritis nodosa and other forms of necrotizing vasculitis.

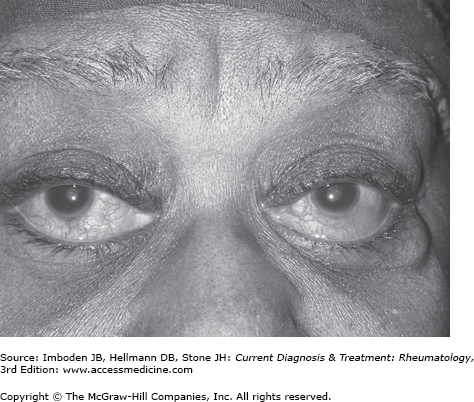

Therapy must reflect the severity of organ involvement. Small, relatively painless infarctions around the nail bed develop in some patients with nodular RA (Figure 42–3). Such lesions, known as Bywaters lesions, do not herald the presence of a necrotizing vasculitis and require no adjustment in the patients’ therapy. With other disease manifestations, however, such as cutaneous ulcers, vasculitic neuropathy, and inflammatory eye disease, glucocorticoids may be required. Glucocorticoids remain a cornerstone of therapy for RV but severe disease is treated generally with two agents, both for greater efficacy in controlling the vasculitis and for sparing of the potential adverse effects of high-dose glucocorticoids. Cyclophosphamide, used to treat many cases of RV, should be used with appropriate caution, given that many patients with RV suffer from substantial disabilities and the effects of previous immunosuppression at baseline. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition and B cell depletion may both be effective strategies in RV and are likely safer than cyclophosphamide in most patients. For this reason, it is appropriate to use TNF inhibitors or rituximab before cyclophosphamide in patients who require more treatment than high-dose glucocorticoids alone.

Cogan Syndrome

- The hallmark of Cogan syndrome is the presence of ocular inflammation and audiovestibular dysfunction. These findings may be accompanied by evidence of a systemic vasculitis.

- Interstitial keratitis is the most common form of ocular involvement.

- Audiovestibular dysfunction may lead to the acute onset of vertigo, tinnitus, nausea, and vomiting.

- Vasculitis in Cogan syndrome may take the form of aortitis, renal artery stenosis, or occlusion of the great vessels.

Cogan syndrome (CS), an immune-mediated condition that primarily affects young adults, is associated with ocular inflammation (usually interstitial keratitis) and audiovestibular dysfunction. This syndrome may be accompanied by a systemic vasculitis of large- and medium-sized arteries that may resemble Takayasu arteritis.

The onset of CS is frequently preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection. Because many features of CS can be caused by known pathogens (eg, Treponema pallidum), CS may be the direct consequence of an unidentified pathogen affecting the eyes, ears, and blood vessels. Alternatively, CS may be the indirect consequence of a pathogen that induces an immune response that continues to attack the host long after the pathogen has been eliminated (ie, molecular mimicry). Neither of these theories has been proved.

The most common ocular manifestation of CS is interstitial keratitis, which is characterized by the abrupt onset of photophobia, lacrimation, and eye pain. CS may also be associated with inflammation in other parts of the eye. Scleritis (Figure 42–4), peripheral ulcerative keratitis, episcleritis, anterior uveitis, conjunctivitis, and retinal vascular disease are all possible.

Patients with CS frequently suffer the acute onset of vertigo, tinnitus, nausea, and vomiting. These symptoms may be enormously disabling. The audiovestibular symptoms may occur before or after the onset of ocular disease, and are often separated in onset by weeks or months. If not treated promptly and aggressively, permanent hearing loss may ensue. Recurrent attacks, which are common, may cause decremental loss of hearing. Ultimately, complete hearing loss occurs in as many as 60% of patients.

The most common manifestation of vasculitis in patients with CS is aortitis. Aortitis may lead to dilatation of the aorta and subsequent incompetence of the aortic valve. Involvement of aortic branches (Figure 42–5) may cause arm or leg claudication. Renal artery stenosis or occlusion of the great vessels may also occur. These manifestations may be accompanied by nonspecific constitutional symptoms, such as malaise, fever, or weight loss as well as arthralgias and frank arthritis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree