Chapter 23 Miscellaneous conditions

KEY POINTS

Septic arthritis is a medical emergency requiring urgent referral for joint aspiration and appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy

Septic arthritis is a medical emergency requiring urgent referral for joint aspiration and appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy Non-pharmacological management of acute gout and pseudogout includes application of ice-packs to the affected joint and initial rest followed by rapid mobilisation

Non-pharmacological management of acute gout and pseudogout includes application of ice-packs to the affected joint and initial rest followed by rapid mobilisation Lifestyle modification advice regarding weight loss, restriction of alcohol and purine-rich foods is a key component of the management of gout

Lifestyle modification advice regarding weight loss, restriction of alcohol and purine-rich foods is a key component of the management of gout Neuropathic arthropathy is an uncommon complication of diabetes mellitus; a high index of suspicion is necessary to avoid delay in treatment and permanent disability

Neuropathic arthropathy is an uncommon complication of diabetes mellitus; a high index of suspicion is necessary to avoid delay in treatment and permanent disability An assessment of physical functioning and activities of daily living is needed in patients with vasculitis to determine appropriate rehabilitation.

An assessment of physical functioning and activities of daily living is needed in patients with vasculitis to determine appropriate rehabilitation.Part 1: Septic arthritis, gout, pyrophosphate arthropathy, sarcoidosis and diabetes mellitus

Septic arthritis is an uncommon but important medical emergency. Although less common than other causes of the acute, hot, swollen joint (Box 23.1); it remains the most important diagnosis to make and treat appropriately. Despite appropriate treatment, septic arthritis is associated with joint destruction and long-term morbidity and functional loss. The incidence of septic arthritis is approximately two to six cases per 100,000 population per year and is highest at extremes of age (Cooper & Cawley 1986, Kaandorp et al 1997a).

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY

Organisms may enter a joint from several routes. The most frequent modes are haematogenous spread, spread from an infected local focus, e.g. osteomyelitis or cellulitis, and direct penetrating injury (Nade 2003).

The most common causative organisms are staphylococcal and streptococcal species with Staphylococcus aureus being the most common (Gupta et al 2001, Kaandorp et al 1997a, Weston et al 1999). Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) septic arthritis is becoming increasingly prevalent (Nixon et al 2007). Gram-negative organisms are less frequently implicated: Haemophilus influenzae is most frequently seen in children. Less frequently encountered organisms include enterobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Risk factors for septic arthritis include underlying joint disease (especially rheumatoid arthritis), prosthetic joints, low socioeconomic class, intravenous drug abuse, alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, previous intra-articular injection and cutaneous ulceration (Mathews et al 2007).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND CLINICAL FEATURES

The classical presentation of septic arthritis is with a short history of a painful, hot, swollen, tender single joint with reduced range of movement (Mathews et al 2007). The most frequently affected joint is the knee. However, involvement is polyarticular in 22% of cases. Fever may be present but is absent in approximately 50% of cases.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of septic arthritis relies upon prompt aspiration of the affected joint prior to commencing antibiotic therapy (Coakley et al 2006). Gram stain, culture and crystal examination of synovial fluid should be performed. A possible infected prosthetic joint requires referral to an orthopaedic surgeon for aspiration in theatre. Blood cultures should always be taken and may identify a causative organism in 33% of cases (Weston et al 1999). Inflammatory markers such as white cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein should be measured but may not be raised in a significant number of cases (Gupta et al 2001, Weston et al 1999). The important differential diagnoses of septic arthritis include crystal arthropathies, e.g. gout and pseudogout, haemarthrosis, reactive arthritis and a monoarticular presentation of an inflammatory arthritis (Box 23.1).

MANAGEMENT

As soon as the joint has been aspirated, intravenous antibiotics should be commenced. The choice of antibiotics will usually be guided by local microbiologists and should be modified in light of the results of Gram stain and culture. Conventionally, the duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy is 2 weeks followed by 4 weeks of oral therapy (Coakley et al 2006). Regular aspiration to dryness should be performed and arthroscopic aspiration may be required.

PROGNOSIS

Septic arthritis is associated with considerable mortality and morbidity (Gupta et al 2001, Kaandorp et al 1997b, Weston et al 1999). The mortality of septic arthritis is approximately 11%. Adverse functional outcome is seen in 21–24% of cases. Factors predicting poor outcome include older age, pre-existing joint disease and the presence of synthetic material within the joint (Mathews et al 2007).

GOUT

Gout is a crystal deposition disease caused by the formation of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in and around joints. It is one of the most common inflammatory arthropathies having a prevalence of 0.52–1.39% and incidence of approximately 13 cases per 10,000 patient-years (Harris et al 1995, Lawrence et al 1998, Mikuls et al 2005, Wallace et al 2004). The prevalence and incidence of gout are thought to be rising (Arromdee et al 2002, Wallace et al 2004). Gout is traditionally sub-divided into primary and secondary gout according to clinical features and risk factors (Table 23.1).

Table 23.1 Comparison of the clinical features and risk factors of primary and secondary gout

| PRIMARY GOUT | SECONDARY GOUT | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Middle-aged | Elderly |

| Gender | Males | Equal gender distribution |

| Acute attacks | Common | Less common May present with tophi alone |

| Distribution | Predominantly lower limb | Equal upper and lower limb |

| Risk factors | Family history of gout | Diuretics |

| Metabolic syndrome | Renal failure | |

| Hypertension | ||

| Obesity | ||

| Hyperlipidaemia | ||

| Insulin resistance | ||

| Excess alcohol consumption | ||

| Purine-rich diet |

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY

Several independent risk factors for the development of gout are recognised (Table 23.1). Primary gout occurs almost exclusively in men and displays a familial tendency: several genetic factors have been identified (Cheng et al 2004, Huang et al 2006, Taniguchi et al 2005, Wang et al 2004). Further independent risk factors include hypertension, obesity and lifestyle factors (excess alcohol consumption, especially beer, and a diet rich in animal purines, for example red meat and seafood) (Choi et al 2004a, 2004b, 2005, Mikuls et al 2005). Gout associates with other features of the metabolic syndrome including hyperlipidaemia, insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease (Abbott et al 1988, Mikuls et al 2005). Diuretic therapy and renal failure are risk factors for secondary gout (Choi et al 2005, Mikuls et al 2005). Osteoarthritis (OA) predisposes to local MSU crystal deposition (Roddy et al 2007).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND CLINICAL FEATURES

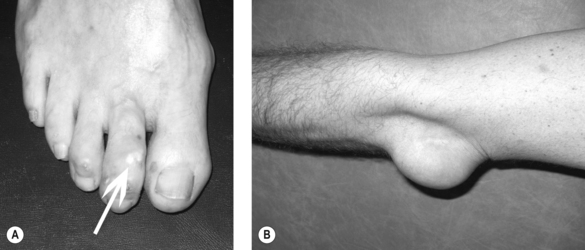

Clinical gout is sub-divided into acute gouty arthritis, interval (intercritical) gout and chronic tophaceous gout. Acute gouty arthritis typically manifests as acute mono-arthritis characterised by severe pain with associated redness, warmth, swelling and tenderness. The first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint is affected most frequently followed by the mid-foot, ankle, knee, finger interphalangeal joints, wrist and elbow. Attacks occur rapidly, often overnight, peaking within 24 hours, before resolving completely over a 2–3 week period. A variable period elapses before the next attack occurs (interval gout). With time, attacks become more frequent, more severe and are more often pauci- or polyarticular leading to chronic tophaceous gout characterised by chronic arthropathy and chalky-white subcutaneous deposits of MSU crystals (tophi). Typical sites for tophi include the toes (Fig. 23.1A), Achilles’ tendons, fingers, elbows (Fig. 23.1B) and, less commonly, the helix of the ear.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Definitive diagnosis of gout requires compensated polarised light microscopy of aspirated synovial fluid or tophaceous material to demonstrate MSU crystals which appear needle-shaped with strong negative birefringence. The differential diagnosis includes septic arthritis, pseudogout, reactive arthritis and palindromic rheumatism (Box 23.1). Crystal arthropathies and septic arthritis can be readily differentiated by crystal examination, Gram stain and culture of synovial fluid.

Measurement of serum urate level (SUA) is an important investigation both to confirm hyperuricaemia and monitor response to treatment. However, the SUA level must be interpreted with caution. Many hyperuricaemic individuals do not develop gout (Campion et al 1987) and SUA is frequently lowered during an attack of acute gout (Schlesinger et al 1997).

MANAGEMENT

Acute gout

Treatment of the acute attack of gout aims to relieve pain by reducing inflammation and intra-articular hypertension. Local application of ice packs four times per day has been shown to reduce pain associated with acute gouty arthritis (Schlesinger et al 2002). Rest and elevation of the affected joint during an acute attack and the use of a bed-cage have been recommended (Jordan et al 2007). Joint aspiration reduces intra-articular hypertension and often provides rapid pain relief. Effective pharmacological therapies for acute gout include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), both non-selective and COX-2 selective agents, low-dose colchicine and systemic and intra-articular corticosteroids (Alloway et al 1993, Fernandez et al 1999, Morris et al 2003, Rubin et al 2004, Schumacher et al 2002).

LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT

Gout is potentially curable. The aim of long-term management is lowering of SUA to facilitate crystal dissolution (Zhang et al 2006).

Modification of provoking factors including lifestyle

Risk factor modification is a key component of the management of gout. Advice regarding weight loss, restriction of alcohol (especially beer) and purine-rich foods should be offered to all patients with primary gout (Jordan et al 2007, Zhang et al 2006). In diuretic-induced gout the diuretic should be stopped or the dose reduced wherever possible.

Urate-lowering therapy

The aim of urate-lowering therapy is to reduce SUA below the saturation threshold of urate (Li-Yu et al 2001). The most commonly used drug in the UK is allopurinol. Other options include uricosuric agents such as sulphinpyrazone, probenecid and benzbromarone. New drugs in development include febuxostat and recombinant uricase.

PYROPHOSPHATE ARTHROPATHY

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystal deposition is a common age-related phenomenon that has three main clinical manifestations: (1) acute synovitis (pseudogout), (2) chronic pyrophosphate arthropathy and (3) the incidental finding of cartilage calcification (chondrocalcinosis) on plain radiographs. Over 40 years of age, the UK community prevalence of pyrophosphate arthropathy is 2.4% and chondrocalcinosis is 4.5% (Neame et al 2003, Zhang et al 2004).

AETIOLOGY

CPPD deposition is most commonly idiopathic being more common in females and with increasing age. In the context of chronic pyrophosphate arthropathy, it associates with OA (Dieppe et al 1982, Zhang et al 2004). CPPD deposition may also occur as a consequence of metabolic disease; most importantly, haemochromatosis, hyperparathyroidism, hypomagnesaemia and hypophosphatasia (Jones et al 1992). Familial CPPD deposition is uncommon although genetic mutations associating with chondrocalcinosis have been identified (Pendleton et al 2002, Williams et al 2003).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND CLINICAL FEATURES

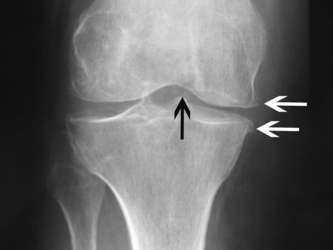

CPPD crystals can be identified by compensated polarised light microscopy of aspirated synovial fluid as rhomboid or rod-shaped crystals with weak positive birefringence. Plain radiographs may show chondrocalcinosis or the structural changes of OA. Chondrocalcinosis mainly affects fibrocartilage and is most commonly seen at the knee (Fig. 23.2), wrist and symphysis pubis. Screening for haemochromatosis, hyperparathyroidism, hypomagnesaemia and hypophosphatasia is indicated under the age of 55 years and when radiographic chondrocalcinosis is particularly striking and widespread (Wright & Doherty 1997).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree