Minimally Invasive and Open Reduction Internal Fixation of Calcaneal Fractures

Bruce J. Sangeorzan

Benjamin P. Amis

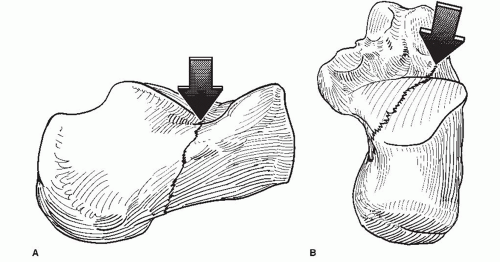

The os calcis fracture pattern is most often characterized by a primary fracture line that begins in the sinus tarsi and is oriented posteriorly and medially, dividing the lateral half of the posterior facet from the medial part of the posterior facet, the tarsal canal, and the medial and anterior facet (Fig. 27.1). There are many secondary fracture lines that may enter the other facets or enter the calcaneocuboid joint. Although the calcaneocuboid joint is less complex and more forgiving, a split in this joint widens the heel and limits function of the transverse tarsal joint.

Fractures of the os calcis are common and disabling injuries (1,2). They tend to occur in males in the prime working years and, as a result, have substantial economic consequences. These fractures account for approximately 60% of tarsal fractures. Some fracture types, such as extraarticular fractures and stress fractures, have a favorable prognosis. Displaced intraarticular fractures are most concerning, and there are different opinions about fracture classification, specific treatment, and indications for operative management.

Fractures of the os calcis are troublesome for several reasons. The soft tissue envelope about the hindfoot is thin with little muscle and highly specialized plantar soft tissues (i.e., heel pad). The medial side of the os calcis is covered by a thin layer of skin; is intimately associated with vessels, nerves, and tendons; and has a complex surface with thick stabilizing ligaments attaching the calcaneus to the talus. The calcaneus also has complex articular surface anatomy. The articulation with the talus has three facets—the posterior, middle and anterior facets—that require a fixed relationship in order to function effectively as a joint. A fracture that disrupts the relationship between the three facets is an intraarticular fracture (Figs. 27.2 and 27.3). The middle and anterior facets, although smaller than the posterior facet, function at a much higher contact pressure. The relationship of these facets must be restored for full function of the joint (3). The calcaneus has a long tuberosity that does not have an articular surface but with important attachments of the Achilles tendon, the plantar fascia, and the blood supply to the body of the calcaneus. The lateral wall of the calcaneus is relatively accessible, flat, and comparatively well suited to internal fixation.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications for open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of calcaneal fractures, though not without controversy, have become more widely accepted (4, 5, 6, 7 and 8). Operative treatment is chosen for those injures that would do poorly without open treatment. The characteristics of the calcaneus fracture that suggest a poor outcome include

High-energy mechanism

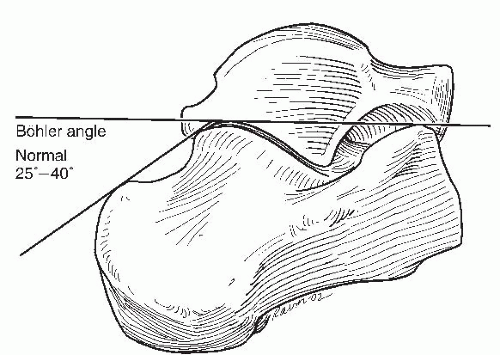

Substantial depression of the tuber or joint angle of Bohler

Widening of the heel

Horizontally oriented talus

Contiguous fractures of multiple bones

Severe soft tissue injury

It is generally accepted that fractures involving the articular surface of the calcaneus with displacement of more than 3 mm in a young, active person should be treated operatively. The threshold for open treatment increases in patients older than 50 years of age as the functional expectations recede and the likelihood of soft tissue complications increases. However, age is a minor factor. Gross widening of the heel with dislocation of the tuberosity laterally may be an indication for open treatment even in a relatively sedentary individual. If the tuberosity is allowed to heal in a grossly lateralized position, weight bearing of any kind, even household ambulation, may exceed the functional ability of the hindfoot in this position. Conversely, the calcaneus fracture with multiple lines of comminution but only limited displacement and widening may be amenable to treatment by closed means in a healthy, active individual (1). Contraindications include severely comminuted fractures, impaired vascularity, infection, severe neuropathy, and an inability to comply with weight-bearing restrictions in the immediate postoperative period.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Important aspects of the patient history unique to those with calcaneus fracture include smoking history; systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, or inflammatory diseases; prior history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT); and medication history. Although there are no absolute indications or contraindications for open reduction, operative treatment should be approached with great caution in patients with diseases that limit healing of the extremities.

Physical Examination

Complete primary and secondary trauma examination—head, chest, abdomen, spine (10% to 15% of patients with calcaneus fractures have concomitant spinal fractures).

Vascular examination of injured lower extremity—dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries.

Sensory examination of injured lower extremity—includes all dermatomes; the tibial nerve crosses the medial side of the calcaneus below the sustentaculum tali and is often injured during the inciting event, manifesting as an incomplete loss of plantar sensation.

Timing of Surgical Intervention

Emergent/urgent treatment—Skin tenting and skin at risk, particularly in tongue-type patterns.

Acute treatment—3 to 14 days after injury to allow soft tissue swelling to recede (demonstrated by the return of skin wrinkling).

Fracture blisters—may require prolonged interval for surgical intervention to allow fracture blisters to dry and the underlying tissues to epithelialize.

Staged treatment of open fractures: Irrigation and debridement within 8 hours of injury with reduction of any fractures causing tension on the skin and application of a well padded splint with the foot in the neutral position with emphasis on elevation and maintenance of a non-weight-bearing status. Definitive fixation at 3 to 14 days as soft tissues allow.

Radiographic Evaluation

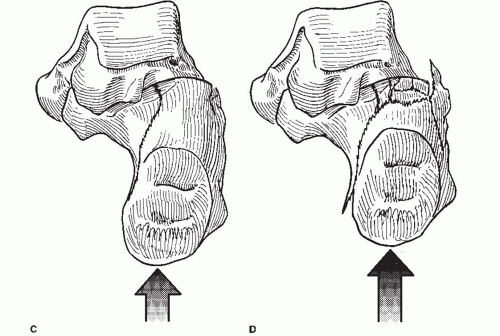

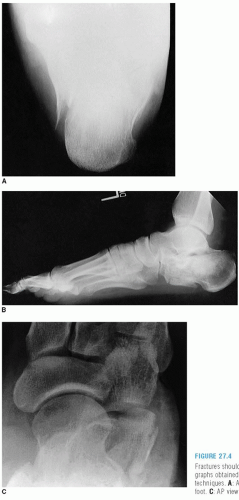

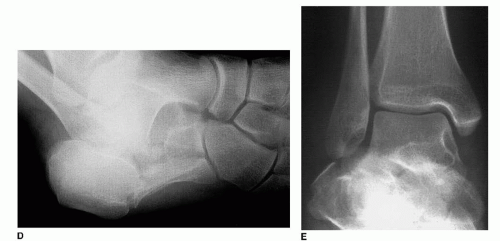

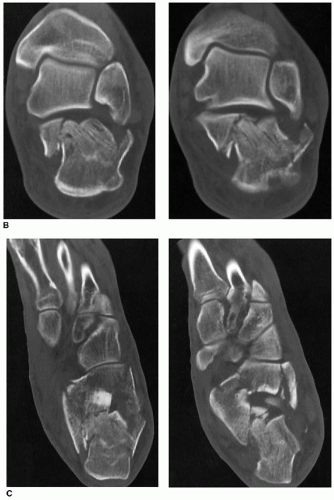

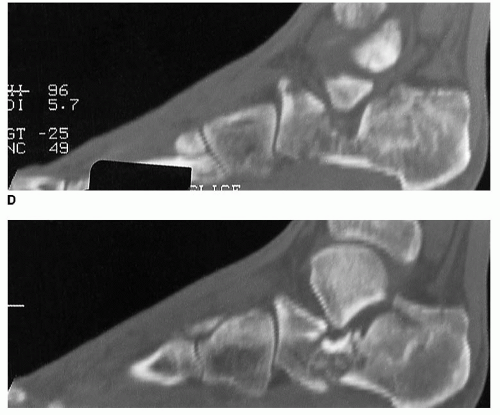

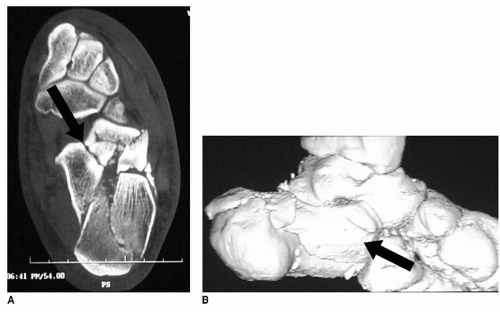

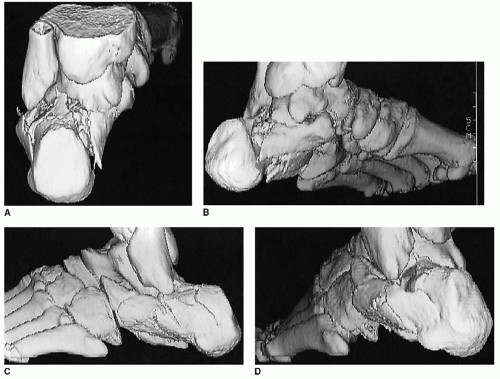

There are many classification systems for calcaneus fractures based on either plain film radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans. However, no classification system has definitively demonstrated a role in determining which fractures need to be repaired and which can be treated closed. All patients require plain radiographs including an anteroposterior (AP), lateral (to assess Böhler angle and angle of Gissane), and Harris axial view (Figs. 27.4, 27.5 and 27.6) (9). Comparison radiographs of the uninjured heel are often beneficial. CT, including coronal, transverse, and sagittal reconstructions, is helpful in almost all intraarticular calcaneus fractures (Figs. 27.7, 27.8 and 27.9).

FIGURE 27.5 An oblique radiograph of the calcaneus, such as the Broden’s view, can demonstrate fractures of the posterior facet (arrow). |

FIGURE 27.7 A: Technique of positioning the extremity for CT scans in transverse (top) and coronal (bottom) plane views. |

FIGURE 27.8 Axial (A), medial (B), lateral (C), and oblique lateral (D) CT views and three-dimensional reconstruction. |

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree