Chapter 6. Methods of treatment

When asked to describe the treatment of any condition, it is a good principle and a safe answer to reply that treatment may be conservative or operative. This is particularly true in orthopaedic surgery, where there are more things to offer the patient than operation. Before selecting the right treatment for the individual patient, the physical requirements of work, home circumstances and motivation, as well as the patient’s likely cooperation with treatment and rehabilitation, all have to be considered.

It must also be remembered that many conditions get better on their own and there is a great temptation for doctors to ‘ascribe to their own skill the kindly work of time’ (John of Salisbury 1180).

Physical therapy

Physiotherapy

An injured limb can be made to work again by a programme of graded exercises to increase the range of joint movement and muscle power using weights, springs and other devices in the ward or gymnasium. Rehabilitation and the supervision of day-to-day progress are essential parts of orthopaedic treatment, but only part of the physiotherapist’s role; a good physiotherapist will also build up the patient’s morale to achieve goals previously thought impossible.

Muscles can be made to contract by applying an intermittent current (faradic stimulation or ‘faradism’) if the patient is unable to contract the muscle voluntarily. Faradism will not work if muscle is denervated, although interrupted direct current and other types of electrotherapy are effective.

Physiotherapists also manipulate the spine and other joints when necessary.

Remedial gymnastics, which once required a separate qualification from physiotherapy, takes the physical rehabilitation of the patient further than routine physiotherapy and is helpful to the young patient with physical or sporting ambitions.

Occupational therapy

The popular concept of occupational therapy is centred on handicrafts such as raffia and wickerwork, but this has little in common with modern occupational therapy, which concentrates on rehabilitating the patient through tasks relevant to work and everyday activities.

Occupational therapy departments include a small kitchen, a bath and a lavatory so that problems can be overcome before the patient leaves hospital, rather than after discharge when there is no help available. The department may also include a small printing press, so that patients can regain fine finger movement while they set type, and a treadle-operated woodworking machine to improve the coordination and strength of the legs, as well as the manual skills of carpentry. Apart from encouraging physical coordination, to produce something useful is tangible evidence of recovery and excellent for morale.

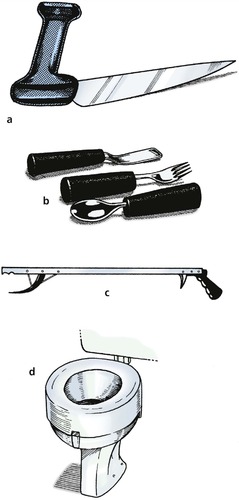

Occupational therapists also provide special cutlery for patients with hand deformities, ‘pickups’ for those who cannot bend and simple gadgets to help with dressing and other activities of daily living (Fig. 6.1).

|

| Fig. 6.1 (a) Knife for patients with rheumatoid arthritis of the hand. (b) Thick handled cutlery for patients with poor grip. (c) ‘Pick-up’. (d) ‘Doughnut’ to increase the height of the lavatory seat for patients with poor hip movement. |

Chiropractors and osteopaths

Chiropractors and osteopaths practise manipulation with great skill but do very little else, and generally work outside the hospital system. ‘Manipulative medicine’ is only one component of physiotherapy and is best conducted where there is access to other forms of treatment.

Aids and appliances

Walking aids

Frames

Frames provide a firm base to lean on and are particularly helpful for the elderly, but they are cumbersome, and most patients want to progress rapidly from the frame to crutches. Wheeled frames (‘Rollators’) are useful in hospital but only work on smooth floors (Fig. 6.2).

|

| Fig. 6.2 (a) Walking frame or ‘pulpit’; (b) ‘quadrupod’ walking stick; (c) wheeled walking frame or ‘Rollator’; (d) two types of walking stick. |

Crutches

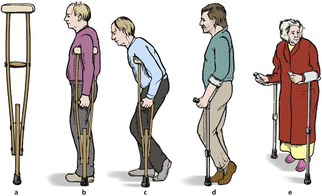

Crutches reduce the load on the lower limbs in patients with fractures or painful joints and help with balance. Three types are in common use (Fig. 6.3).

|

| Fig. 6.3 (a) Axillary crutch; (b) axillary crutch used correctly; (c) axillary crutch used incorrectly; (d) elbow crutch; (e) gutter crutch. |

Axillary crutches. The traditional axillary crutch has the great disadvantage that leaning on the upper end presses the radial nerve against the humerus and causes a ‘crutch palsy’. When axillary crutches are used, the elbows should be locked straight; the upper end is not for weight-bearing.

Elbow crutches. To avoid this problem, elbow crutches may be used and are preferable to axillary crutches, but have the disadvantage of being easily broken, particularly by heavy patients.

Gutter crutches. Patients with deformed hands cannot use either axillary or elbow crutches effectively and prefer gutter crutches so they can use their forearms for weight-bearing.

Walking stick

A walking stick reduces the load on an injured limb if it is pushed against the ground when the injured limb is taking weight. Stand on a bathroom scale and press a stick against the floor to see how this happens (Fig. 6.4). Used correctly, a third of the body’s weight can be taken through the stick, but only if the stick is put to the ground at the same time as the injured leg. This usually means holding the stick in the hand opposite the injured limb, but right-handed patients with injuries of the right leg find this difficult.

|

| Fig. 6.4 Mechanism of action of a walking stick. When the stick is pushed against the floor, the patient’s weight on the limb is reduced, relieving pressure on joints. |

Appliances

Surgical appliances include splints and braces to support limbs, prostheses to replace absent parts of the body, surgical shoes and spinal supports. Appliances are expensive, although economical by comparison with hospital admission.

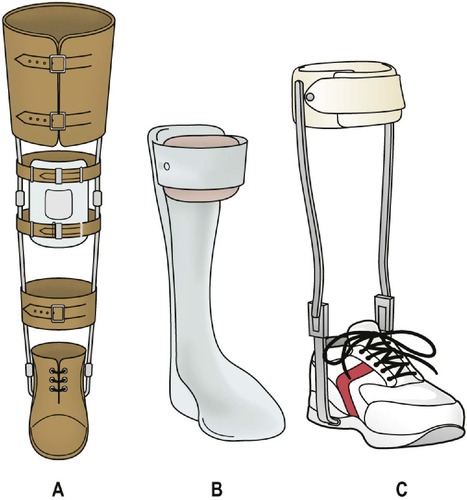

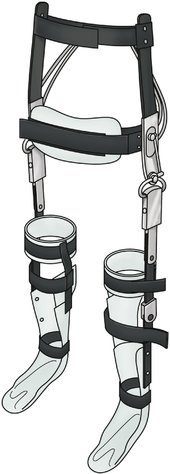

Orthoses

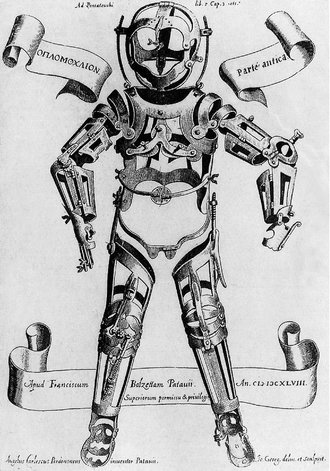

Orthoses, or braces, are used to support limbs (Fig. 6.5). A leg with no active dorsiflexors of the ankle is helped by a device to lift the foot, and an unstable knee is helped by a simple exoskeleton or caliper. The design and development of orthoses has advanced enormously in recent times and many heavy and unsightly devices of the past (Fig. 6.6) can be replaced with lightweight cosmetic orthoses. Close cooperation with the fitter, or orthotist, is essential if the patient is to receive the best appliance for his or her own requirements.

|

| Fig. 6.5 Modern types of orthosis: (a) weight-relieving caliper; (b) below-knee caliper with T strap; (c) cosmetic drop foot splint. |

|

| Fig. 6.6 An early orthosis. From Fabricius ab Aquapendente, Opera Chirurgica (1647), Padua. By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London. |

For patients with paraplegia, complex braces can also be made that support the lower limbs well enough to stand, and in some cases walk, unaided (Fig. 6.7).

|

| Fig. 6.7 A modern orthosis with padded leather waistband and steel limb supports. |

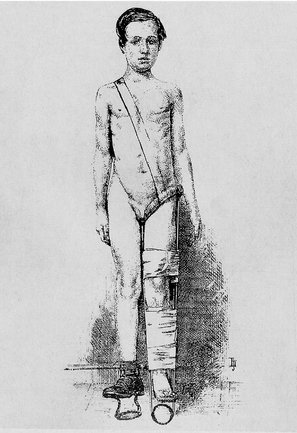

Weight reduction

In the past, it was considered important to relieve the weight taken by an injured or diseased limb and many devices existed to achieve this (Fig. 6.8). Protection from full load-bearing is still important for some conditions, particularly healing fractures.

|

| Fig. 6.8 An ischial-bearing, weight-relieving, patten-ended caliper. From Thomas H O (1876) Diseases of the Hip, Knee, and Ankle Joints. By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London. |

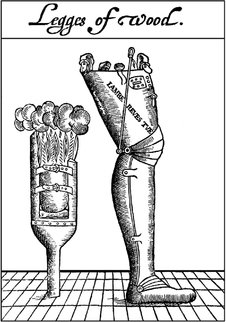

Prostheses

Artificial limbs, or ‘exoprostheses’, have also improved in recent years (Fig. 6.9 and Fig. 6.10), and fitting limbs is now a specialty in its own right. This service is provided at Artificial Limb and Appliance Centres (ALACs), which are established regionally and are not available in every city.

|

| Fig. 6.9 An early artificial limb. From A Discourse of the Whole Art of Chirurgerie (1612). By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London. |

|

| Fig. 6.10 A modern socket (without waistband). |

Everyday problems of maintaining artificial limbs, including repair and replacement of the limb, and practical problems such as pressure sores on the stump are best managed by these centres and it is always worth discussing difficulties with the appropriate specialist at the limb centre. The limb centre can also help by explaining the practical problems of amputation with the patient before operation, which not only helps the patient adjust to the inevitable problems but also helps the surgeon choose the right prosthesis for the individual and ensure that the stump is as good as can be achieved.

Prostheses for the upper limb present a number of different problems. A working prosthesis to replace the hand usually includes a hook of some type if it is to be of practical use; these can be unsightly. Cosmetic substitutes for the hand are seldom functional. Many patients have two prostheses, one for the working day and another for social occasions where appearance is more important than function.

The design and selection of prostheses is a subject in itself.

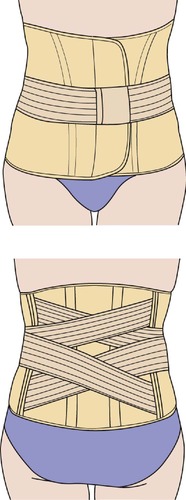

Spinal supports

Spinal supports were once used extensively for tuberculosis and other infections. These diseases are now uncommon and have been replaced by low back pain as the commonest indication for a lumbosacral support (Fig. 6.11). Spinal supports restrict movement of the lumbar spine and should be prescribed sparingly, especially in obese patients, who can expect little support from a lumbosacral corset that cannot get near the pelvis because of fat.

|

| Fig. 6.11 A lumbosacral support. |

Collars

Collars to support the neck are used after trauma and for patients with acutely painful necks. Do not use the term ‘cervical collar’: a collar cannot be worn anywhere else.

Footwear

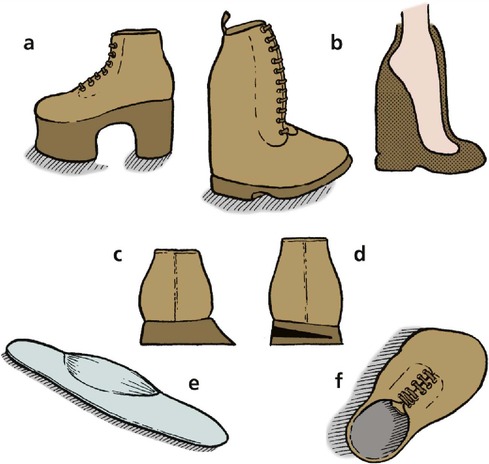

Surgical shoes or boots are prescribed for patients with foot deformities. Normal shoes are designed for normal feet and patients with abnormal feet are sometimes disabled only because they cannot find shoes that fit. Many patients with quite severe deformities can cope in soft shoes such as trainers, but specially made shoes will be needed if these are unsatisfactory. There are several types of appliance (Fig. 6.12):

|

| Fig. 6.12 Modifications to shoes and footwear: (a) raised sole and heel; (b) boot to accommodate fixed equinus deformity; (c) float to heels; (d) wedge to heel; (e) an insole; (f) surgical shoe for foot deformity. |

• Boots with a firm ankle support for patients with unstable ankles.

• Floats to the sole and heel for feet that tend to roll over.

• Insoles: soft insoles are helpful for patients with prominent metatarsal heads; firm moulded insoles support flat feet.

• Raises to the sole or heel to compensate for limb inequality.

These simple devices may be enough to make operation unnecessary.

Community services

Social services

Many patients have been helped more by social services or modifications to their home than by hospital treatment. Elderly patients unable to fend for themselves may need a home help to assist with housework and shopping rather than a total hip replacement, and the insuperable problem of climbing stairs can sometimes be solved by fitting a stout handrail.

These aspects of patient care cannot be ignored just because they happen outside hospital.

Warden-controlled accommodation is suitable for many elderly or infirm patients and allows them to live an independent existence in a home of their own. As the age of the population increases, small developments of single-storey accommodation designed specifically for the elderly are seen more often.

Those who cannot cope with warden-controlled accommodation need long-term residential care. Such accommodation may be provided either by local authorities or by private individuals but is under great pressure and the level of care offered is very variable.

If a patient is to be cared for by the family it is important to consider before discharge the impact such arrangements will have upon the rest of the family. Home visits from social workers, occupational therapists and the local health visitor are very helpful.

Resettlement

Patients who cannot be restored to their former work need to be resettled or retrained. A man engaged in heavy manual work and unable to lift after a back injury must find another job; a builder’s labourer with a stiff foot needs work that does not involve walking over rough ground. These problems commonly occur in patients with little academic aptitude and the selection of a new job can be difficult.

Advising a patient to give up his or her work and undergo retraining involves a great deal of thought and sympathetic assessment to determine the patient’s own particular skills (Fig. 6.13). This is best done in a resettlement or retraining centre, contacted through the local Disablement Resettlement Officer. It is not uncommon to find that a resettled patient can earn more in the new job and enjoys it better. On the other hand, ‘outdoor people’ are always unhappy at the prospect of working indoors, seated at a bench doing repetitive manual tasks, and need much encouragement.

|

| Fig. 6.13 A skill centre for retraining injured patients. By kind permission of Skills Training Agency, Sheffield. |

Rehabilitation centres

Rehabilitation of the severely injured patient requires a coordinated approach and a sense of direction, which is missing when the patient is an outpatient receiving a little physiotherapy here and some occupational therapy there while they wait their turn for industrial retraining. Combining all these facilities under one roof, where patients receive more concentrated and continuous treatment than an ordinary hospital can offer, makes the task of rehabilitation a full-time occupation. This can achieve results not possible if patients are at home dwelling on their problems.

Drugs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used for the conservative management of joint disease. Many such drugs are available and there is little to choose between them, but patients often do not react predictably. One patient may be completely relieved by a drug that has no effect on a patient with the same condition, and several may have to be tried before finding one that ‘suits’ the individual.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree