Medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction

Cory O. Nelson

Neal S. ElAttrache

The medial structures of the elbow are subjected to significantly high forces in the overhead athlete (21) and the anterior bundle of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is the main restraint to these valgus forces in the flexed, throwing position (9,14). UCL insufficiency in overhead athletes was once considered to be a career-ending diagnosis. Since the first UCL reconstruction performed by Dr. Frank W. Jobe in 1974, surgical reconstruction has afforded these athletes the opportunity to return to their preinjury level of play with predictable outcomes.

In the original description of the surgical technique, the common flexor-pronator tendon was detached from its origin on the medial epicondyle and the ulnar nerve was transposed submuscularly (13). A long-term follow-up study at our institution using this technique showed good to excellent results in 80% of patients; however, a 21% complication rate was reported associated with dysfunction of the ulnar nerve (8). Due to the high incidence of postoperative ulnar nerve symptoms and need for secondary procedures, a muscle-splitting technique without ulnar nerve transposition was developed, which is described in this chapter (18,19). While others routinely transpose the ulnar nerve when performing UCL reconstructions with good outcomes (3), Thompson et al. (19) reported good to excellent results and significantly less ulnar nerve morbidity in 31 of 33 (94%) patients without transposition using this muscle-splitting technique.

Although variations from the original reconstruction technique with respect to graft passage and fixation have been reported, the principles of the surgical technique remain consistent to restore medial elbow stability in the overhead athlete. The insufficient UCL should be reconstructed using a free tendon autograft, with stable fixation, and tensioned at an isometric point through elbow range of motion. In Dr. Jobe’s own words, “the goal is to put a good piece of collagen in the right orientation.”

DIAGNOSIS AND DECISION MAKING

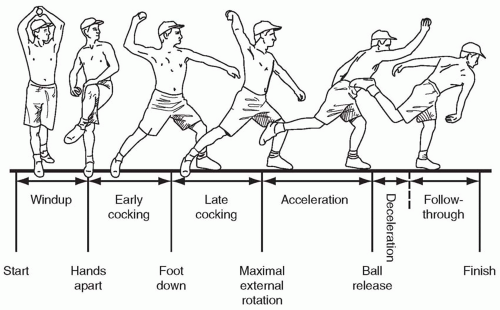

The diagnosis of valgus instability of the elbow due to UCL insufficiency is based upon an accurate history, physical examination, and radiographic studies. Athletes usually present with medial elbow pain in the late cocking or acceleration phases of repetitive overhand throwing activities (Fig. 2.1) (6). Changes in velocity, accuracy, and stamina while throwing are other important factors to obtain from the patient’s history. History may reveal an acute injury of sharp pain and/or a “pop” in the medial elbow with inability to continue performing, a gradual onset of medial-sided pain over time with throwing, or significant pain after a strenuous throwing load with unsuccessful attempts to throw above 50% to 75% of maximum function. Neurologic complaints of paresthesias or radicular symptoms in the ulnar nerve distribution should be elicited and documented.

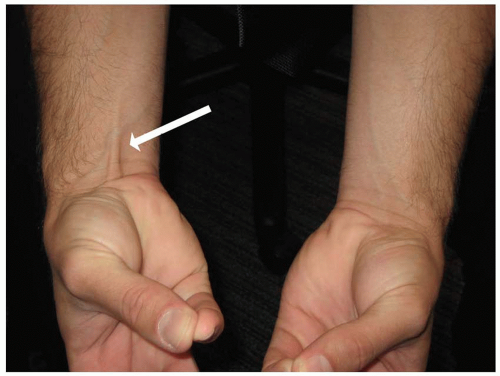

A complete physical examination of the elbow including range of motion, palpation of the bony landmarks as well as the UCL and flexor-pronator tendon origin, and forearm and elbow muscle strength is performed. Tenderness over the UCL or flexor-pronator muscle unit is indicative of local inflammation. Pain with resisted wrist flexion or pronation should be assessed along with palpation for defects in the tendinous origin which may be indicative of flexor-pronator injury rather than UCL instability. The patient should also be inspected for the presence or absence of a palmaris longus tendon (Fig. 2.2).

A detailed neurovascular assessment is also completed with careful attention paid to ulnar nerve motor and sensory function. Palpation of the ulnar nerve proximal and distal to the epicondyle should be performed, and a gentle anterior force applied proximally will assess if the nerve will sublux over the medial epicondyle out of the cubital tunnel. A Tinel sign is also elicited over the cubital tunnel.

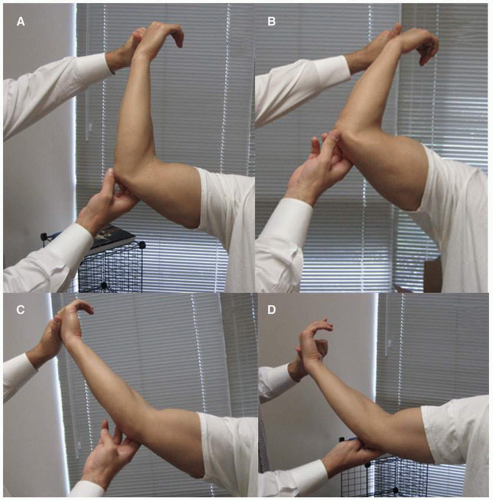

Valgus instability is tested with the elbow in 25 to 30 degrees of flexion and the patient’s hand and wrist secured between the examiners forearm and trunk (Fig. 2.3). A valgus force is applied to the elbow while concurrently palpating the UCL. Pain, tenderness, and medial joint space laxity are assessed. The “milking maneuver” is a sensitive test for UCL damage and is performed by grasping the thrower’s thumb with the arm in the cocked position (90 degree shoulder abduction and 90 degree elbow flexion) and applying a valgus stress by pulling down on the thumb (4) (Fig. 2.4A). Pain in the medial elbow is a positive result. This maneuver can also be performed dynamically with the shoulder held in 90 degrees of abduction as the elbow is ranged with a constant valgus force applied (Fig. 2.4B-D). Valgus extension overload is tested by the examiner placing a valgus force on the elbow and quickly moving the elbow into maximal extension. Pain in the posterior compartment is consistent with posterior impingement from a posteromedial olecranon osteophyte or olecranon fossa overgrowth.

Radiographic studies are helpful if positive, but a negative study should not rule out the diagnosis of UCL insufficiency. As such, the diagnosis remains a clinical one. Radiographs may add valuable information for preoperative planning such as ossification within the ligament, intra-articular loose bodies, posterior or marginal osteophytes, or osteochondritic lesions of the capitellum. Stress radiographs may demonstrate significant medial joint line widening. Abnormal stress radiographs or calcifications in the ligament without symptoms of pain or instability do not justify surgical intervention.

FIGURE 2.2 Presence (patient’s right—arrow) and absence (patient’s left) of Palmaris Longus tendon on physical examination wrist flexion combined with thumb and small finger opposition. |

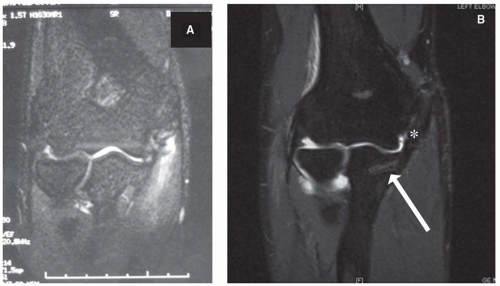

MRI can be very helpful in both the chronic and acute setting to evaluate the UCL (Fig. 2.5A). MRI is also useful in evaluating the articular surfaces, as well as identifying loose bodies. There is debate as to whether or not intra-articular contrast increases the sensitivity of the study in evaluating the UCL. We routinely obtain a noncontrast MRI, except in the setting of an athlete who has already had a reconstruction and the graft is being evaluated (Fig. 2.5B).

Once the diagnosis is made, a course of nonoperative treatment is initiated. Rest from all throwing activities during the initial 4 to 6 weeks is mandatory. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, ice, and other physical modalities are used early to decrease inflammation. Steroid injections are generally avoided as they have not

been found to be helpful and may cause further ligament degeneration. Although not throwing, a total-body training program as well as periscapular and rotator cuff strengthening programs are begun early. Trunk, core, and shoulder muscle weakness with throwing may increase the valgus forces placed on the elbow and severely hinder attempts to return to throwing. After the rest period and full painless motion is achieved with normal strength, a throwing program is begun.

been found to be helpful and may cause further ligament degeneration. Although not throwing, a total-body training program as well as periscapular and rotator cuff strengthening programs are begun early. Trunk, core, and shoulder muscle weakness with throwing may increase the valgus forces placed on the elbow and severely hinder attempts to return to throwing. After the rest period and full painless motion is achieved with normal strength, a throwing program is begun.

FIGURE 2.4 A: Milking test. B-D: Dynamic valgus examination of the elbow in varying degrees of elbow flexion. |

FIGURE 2.5 A: MRI coronal image of UCL rupture. B: Gadolinium enhanced MRI after UCL reconstruction showing an intact graft (asterisk) and tenodesis screw fixation in the ulna (arrow). |

If elbow stability and pain relief are the main goals, nonoperative treatment is usually successful. This is the case in most noncompetitive, recreational, or occupational circumstances where activity modification can also be incorporated into the nonoperative treatment algorithm. However, surgery is recommended for athletes who desire to return to highly competitive overhead or throwing sports and have failed to improve despite nonoperative treatment.

Medial elbow instability due to UCL insufficiency has been shown to cause ulnar nerve symptoms in 24% (19) to 41% (8) of overhead athletes. Traction on the nerve with repetitive medial joint space widening or abrasion by posteromedial osteophytes may cause paresthesias that affect the player’s ability to perform. This situation is also justification for surgical reconstruction to restore medial stability.

In patients without loose bodies, posterior osteophytes requiring removal, or ulnar nerve symptoms, the ulnar nerve is not transposed. This muscle-splitting technique allows adequate exposure for tunnel creation, graft passage, and the flexor-pronator origin to remain attached at the medial epicondyle since the ulnar nerve is not routinely transposed.

REPAIR VERSUS RECONSTRUCTION

Primary repair of the UCL has been reported, but in general has led to inferior results when compared to reconstruction (5). Andrews and Timmerman (2) reviewed the outcome of elbow surgeries in professional baseball players, and the two patients who had direct primary UCL repair were not able to continue to play. Conway et al. (8) reported a 50% return to preinjury level of play with repair, compared to 68% in reconstructed patients. Finally, Azar et al. reported return to competitive throwing in five of eight primary repairs (63%) versus 81% with reconstruction. In younger (average age 17.2 years), nonprofessional athletes, Savoie et al. (16) described good to excellent results in 93% of the patients treated with primary repair. They concluded that primary repair may be a viable option for younger, nonprofessional athletes.

We have found, along with others, more predictable and consistent long-term results with reconstructing the ligament. Therefore, reconstruction of the UCL with free autologous tendon graft is our surgical treatment of choice.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Modified Jobe Technique

The procedure is carried out using a pneumatic tourniquet with the patient in the supine position and the use of an arm board.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree