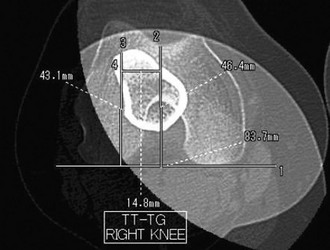

Chapter 88 Numerous surgical procedures have been described for the treatment of patellar instability, most with generally favorable success rates. The medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), the primary soft tissue passive restraint to pathologic lateral patellar displacement,1 is torn when the patella dislocates.2,3 There has been a great deal of interest recently in soft tissue procedures that address the MPFL. Techniques have been described to repair2–5 or reconstruct6–9 the MPFL in an attempt to restore its function as a checkrein. Regardless of which approach is taken, successful surgical treatment requires that the surgeon have a thorough understanding of the relevant anatomy and a working knowledge of patellofemoral biomechanics. Computed tomography scans in the axial plane are used to evaluate patella tilt, subluxation, and trochlear morphology. Superimposed axial images through the trochlear groove and tuberosity are used to measure the tibial tuberosity–trochlear groove distance (Fig. 88-1). Patella height index calculation can be made from the sagittal images. Although computed tomography scans are ideal for showing the bony anatomy, magnetic resonance imaging shows the soft tissue injuries, including MPFL tears, meniscus tears, and chondral lesions. MPFL reconstruction is indicated for patients with symptomatic recurrent lateral subluxation or dislocation episodes for whom nonoperative treatment (including activity modification, physical therapy, and bracing) has failed. Tibial tuberosity osteotomy procedures such as the Elmslie-Trillat, which directly decrease the quadriceps angle by medializing the tibial tuberosity, have a theoretical advantage in patients with greater degrees of malalignment. The Fulkerson anteromedialization osteotomy is preferred for patients with malalignment and degenerative changes.10 MPFL reconstruction or repair can be combined with distal osteotomy if neither alone can provide adequate stability. Lateral retinacular release is reserved for patients with excessive lateral patellofemoral pressure; it is ineffective as an isolated procedure for patients with instability. Some authors recommend MPFL repair after first-time patellar dislocation.3 We usually treat an initial subluxation or dislocation episode nonoperatively but may repair an acute MPFL tear when surgery is indicated for concomitant intra-articular disease (such as an osteochondral fracture, large loose body, or meniscus tear). MPFL repair may also be used to treat recurrent instability. With repeated instability episodes, the MPFL becomes attenuated and functionally incompetent. To reestablish the normal checkrein effect, the MPFL is tightened by cutting, shortening, and reattaching it at the patellar or femoral insertion or by midsubstance imbrication. Once adequate anesthesia has been established, a comprehensive examination is performed. It is usually easier to characterize patellar stability, translation, and tilt when the patient is anesthetized. With the knee in extension, the position of the patella is determined at rest and with a lateral translation force applied (Fig. 88-2A). Even an unstable patella will not stay dislocated unless the knee is maintained in a flexed position. It is important to compare the amount of translation on the symptomatic side with the normal lateral patellar translation in the contralateral knee. The examiner should use his or her thumb to push the patella laterally and assess the amount of translation as well as the consistency of the end point. It is also important to measure medial translation (Fig. 88-2B). Rarely, medial instability may be confused with lateral instability, especially if the patient has had an overaggressive previous lateral retinacular release. It is also important to assess the patient for lateral retinacular tightness. If the examiner is unable to evert the lateral edge of the patella to the neutral or horizontal position, and if the patient’s symptoms and preoperative radiographs are consistent with excessive lateral pressure, consideration should be given to a concomitant arthroscopic lateral retinacular release.

Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Reconstruction and Repair for Patellar Instability

Preoperative Considerations

Imaging

Other Imaging Modalities

Indications and Contraindications

Surgical Technique

Examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Reconstruction and Repair for Patellar Instability