Medial Epicondylitis/Tendinosis

Robert P. Nirschl

INTRODUCTION

As with the lateral elbow, we prefer the term tendinosis to epicondylitis as the problem is in the common flexor tendons and not the epicondyle. The histopathology also has no inflammatory cells (1,2). Medial elbow tendinosis is less common than lateral elbow tendinosis by a factor of one to five (3).

INDICATIONS

As with lateral epicondylitis, the indication for surgery is pain that limits daily activity and/or interrupts sleep (Table 25-1). The duration of nonoperative management is usually 6 to 9 and ideally at least 12 months. All conservative measures should have been tried. At least one cortisone injection is helpful to isolate the lesion location while offering temporary pain control. Limited temporary pain control of this therapy strengthens the indications for surgery. Total failure (e.g., no pain control) raises concern about the etiology of symptoms (e.g., emotional factors or secondary gain motivation) or possibly inadequate injection technique. For further details, review Chapter 24 (lateral epicondylitis) sections Indications/Contraindications and Preoperative Planning.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

The most significant contraindication is a history and physical exam that does not accurately coincide with expectations of medial epicondylitis. Poor motivation, workers’ compensation, and unrealistic expectations are also issues of concern and to be considered before surgical intervention is carried out. Individuals who are improving or who have had symptoms less than 6 months are generally not considered candidates for surgery.

PRESENTATION AND CLASSIFICATION

Medial epicondylitis is a consequence of acute or chronic loads applied to the flexor-pronator mass of the forearm as a result of activity related to the medial elbow and proximal forearm (2). It is approximately one-fifth as common as lateral epicondylitis and has a similar demographic profile. The concomitant presence of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow is seen in 30% to 50% of patients and may be the primary management concern (4,5,6,7 and 8). Physical examination reveals common flexor origin and direct epicondylar tenderness and indirect pain with resisted pronation and wrist flexion. Ulnar nerve examination may demonstrate a positive Tinel sign, elbow flexion test, or nerve compression test. Valgus stress examination is essential to assess ulnar collateral ligament sprain or medial instability either as an associated concern or as the primary process. Subluxation of the medial head of the triceps and medial antebrachial cutaneous neuropathy (MABCN) should be ruled out as well (9).

Plain radiographs are helpful to evaluate additional diagnoses, most commonly degenerative arthritis (which may require diagnostic Xylocaine injection of the elbow to differentiate an

intra-articular versus an extra-articular source of symptoms). Valgus stress radiographs should be obtained if indicated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful if symptoms suggest additional abnormalities but is usually not required as this is primarily a clinical diagnosis in the usual case.

intra-articular versus an extra-articular source of symptoms). Valgus stress radiographs should be obtained if indicated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful if symptoms suggest additional abnormalities but is usually not required as this is primarily a clinical diagnosis in the usual case.

TABLE 25-1 Tendinosis Phases of Pain | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Medial epicondylitis is classified with a combined epicondylitis and ulnar neuropathy classification system (5). To simplify the original classification, type I is an isolated medial epicondylitis, and type II is medial epicondylitis with an associated ulnar neuropathy. This may be further classified as (a) minimal or (b) moderate ulnar nerve severity.

The initial management of type I medial epicondylitis is similar to lateral epicondylitis including corticosteroid injection, counterforce bracing, wrist splinting, and a conditioning program (7,10). Injections should be placed at the proximal anterior aspect of the common flexor origin just distal to the epicondyle with the elbow in extension to avoid the ulnar nerve (11) and the anterior oblique ligament. Instances of type I and type II medial epicondylitis that fail to respond to nonoperative management are indications for surgical intervention.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

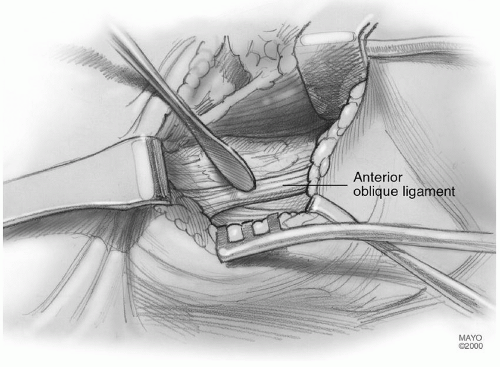

The surgical procedure of choice relates to the classification of medial epicondylitis. Operative management of type I medial epicondylitis involves medial common flexor origin debridement alone (2,5,7,12). In the past, percutaneous release was reported but is currently not recommended (13). Type II medial epicondylitis may require ulnar nerve decompression including cubital tunnel release (2,3,5,7,12). Ulnar nerve transfer is indicated for symptoms caused by nerve tension (e.g., skeletal or dynamic valgus instability) or a completely dislocating nerve, both uncommon (7,14). On occasion, a subluxing medial head of the triceps may occur and should not be confused with a dislocating nerve (9). Occasionally, a small epicondylar exostosis may be removed if present. Medial epicondylectomy should be avoided as anterior epicondylar removal (for medial epicondylitis) and posterior epicondylar removal (for the ulnar nerve) may result in compromise of the anterior oblique ligament origin. Tendinosis usually involves the flexor carpi radialis and the medial side of the pronator teres. It is best to excise this tissue longitudinally in elliptical fashion thereby preserving all normal tendon attachments (2,5,7,12,15).

Valgus instability, if present, may be operatively treated at the same setting with anterior oblique ligament reconstruction in association with a longitudinal split in the common flexor origin. Exposure to the area of ligament repair or reconstruction by this exposure is less punishing, and the ulnar nerve does not require transfer in most instances. Ulnar nerve complications and delayed rehabilitation secondary to prior techniques of total release of the flexor-pronator mass and submuscular nerve transfer are thereby largely eliminated.

The medial conjoint tendon (MCT) is the primary anatomic focus in medial

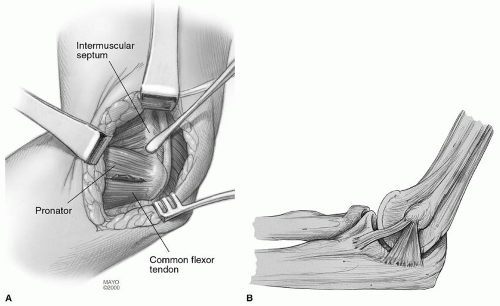

epicondylitis. It lies immediately anterior and superficial to the anterior oblique ligament with, in most cases, no identifiable interval between these two structures. The MCT serves as the tendon origin for the flexor-pronator mass musculature including the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), flexor carpi radialis, the pronator teres, the palmaris longus, and the deeper positioned flexor digitorum sublimus. At the level of the medial epicondyle, the tendon is fully conjoint. The medial conjoint muscle tendon unit can extend distally up to 10 to 12 cm into the forearm, but the usual is 3 to 4 cm. Gross pathologic involvement of the tendon is usually seen within the proximal 2 to 3 cm of the tendon, the level where it is fully conjoint. It is at this level that the surgical debridement in medial epicondylitis is conducted (Fig. 25-1). The anterior oblique ligament remains under the posterior border of the MCT throughout the course of the anterior oblique ligament (Fig. 25-2).

SURGERY

Type I Medial Epicondylitis: Isolated Medial Epicondylar Debridement

Prior to anesthesia, clearly reidentify the area of tenderness as this will identify the area of pathology.

After induction of a general anesthetic, the arm is prepped and draped in usual fashion. A longitudinal incision is created starting 1 cm posterior to the proximal margin of the medial epicondyle and extending distally for 3 to 4 cm (7,12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree