Chapter 1 Medial and Anterior Knee Anatomy

MEDIAL ANATOMY OF THE KNEE

The medial anatomy of the knee consists of several layers of structures that work together to provide stability and function. Authors have used a variety of anatomic terms and descriptions that, unfortunately, have created ambiguity and confusion regarding this area of the knee. Two anatomic classifications or descriptions have been proposed to aid in the understanding of the relationships of the medial knee structures. These include a layered approach,46 which describes the qualitative relationship of each medial structure, and a more quantitative description,28 which details the exact attachment site and origin of each structure. In this chapter, both approaches are presented; however, emphasis is on the precise anatomic relationships that provide a more thorough understanding of the structures compared with the layered approach.

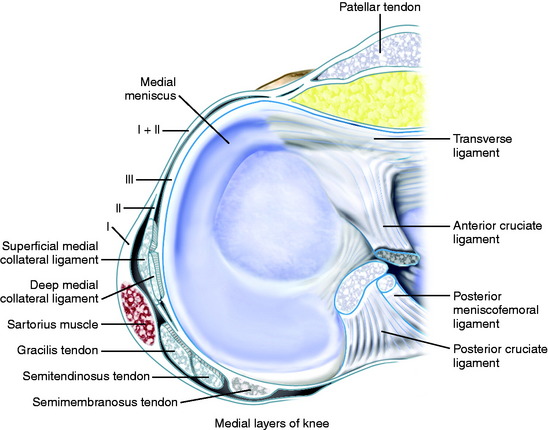

Medial Layers of the Knee

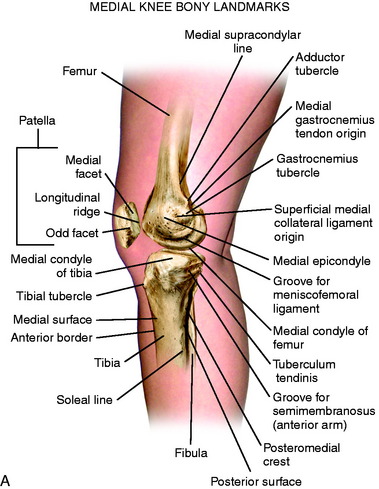

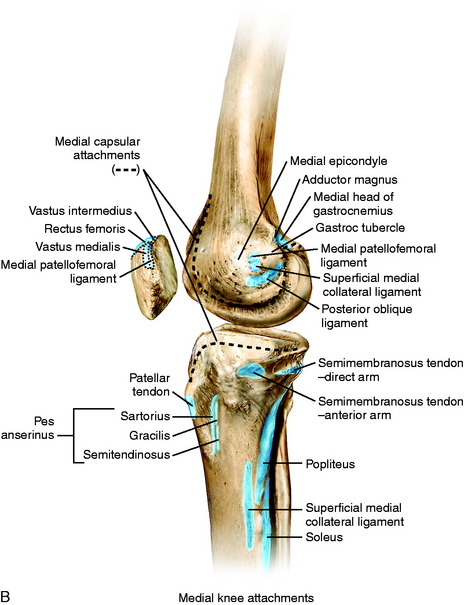

The three-layer description of the medial anatomy of the knee was proposed by Warren and Marshall.46 In this approach, layer 1 consists of the deep fascia or crural fascia; layer 2 includes the superficial medial collateral ligament (SMCL), medial retinaculum, and the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL); and layer 3 is composed of the deep medial collateral ligament (DMCL) and capsule of the knee joint (Fig. 1-1). For this chapter, the term medial collateral ligament (MCL) has been selected instead of tibial collateral ligament because it represents the term most commonly used in the English literature. The medial structures identified as important in preventing lateral patellar subluxation are the MPFL and the medial patellomeniscal ligament, which inserts onto the inferior third of the patella to the anterior portion of the medial meniscus and runs adjacent to the medial fat pad. The medial parapatellar retinaculum and so-called medial patellotibial ligament (thickening of the anterior capsule inserting from the inferior aspect of the patella to the anteromedial aspect of the tibia) are retinacular tissues that have been described; however, these structures are not believed important to providing patellar stability.

The layered approach is important because the ligaments and soft tissues on the medial side of the knee are not discrete, individual structures like the SMCL, but rather, fibrous condensations within tissue planes.46 This qualitative description of anatomy assists in understanding the spatial relationships of these structures and how they function to support the knee.48 It is equally important to understand the quantitative anatomy from precise measurements of the attachments and origins of each individual structure. The complex medial anatomy of the knee has been illustrated in the past with oversimplification of the soft tissue attachments to bone and other structures, which makes it difficult to compare the origins, insertions, and courses of the many separate structures among studies.3,4,12,15,30,41,46 LaPrade and coworkers28 recently published detailed quantitative measurements that provide a better understanding of the medial knee anatomy.

Layer 1: Deep Fascia

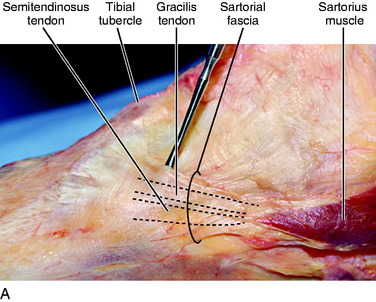

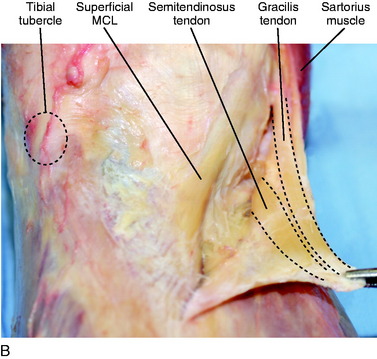

Layer 1 (see Fig. 1-1) consists of the deep fascia that extends proximally to invest the quadriceps, posteriorly to invest the two heads of the gastrocnemius and cover the popliteal fossa, and distally to involve the sartorius muscle and sartorial fascia. Anteriorly, layer 1 blends with the anterior part of layer 2, approximately 2 cm anterior to the SMCL.46 Inferiorly, the deep fascia continues as the investing fascia of the sartorius and attaches to the periosteum of the tibia. Layers 1 and 2 are always distinct at the level of the SMCL unless extensive scarring has occurred.46 The gracilis and semitendinosus tendons are discrete structures that lie between layers 1 and 2 and are easily separated from these two layers. However, according to Warren and Marshall,46 these tendons will occasionally blend with the fibers in layer 1 anteriorly before they insert onto the tibia. As depicted in Figure 1-2, dissections and clinical experience of the authors of this chapter concur in that there is a blending of layer 1 with a confluence of the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons at their common insertion onto the tibia; however, they are easily found as discrete structures more posteriorly. Thus, it is the recommendation of the authors of this chapter that when attempting to harvest the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons for an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, these tendons initially be identified 2 to 3 cm posterior and medial to the anterior tibial spine. This will allow for easier visualization of the tendons, which can then be traced to their insertions on the anterior tibia to allow for maximal tendon length at the time of harvest.

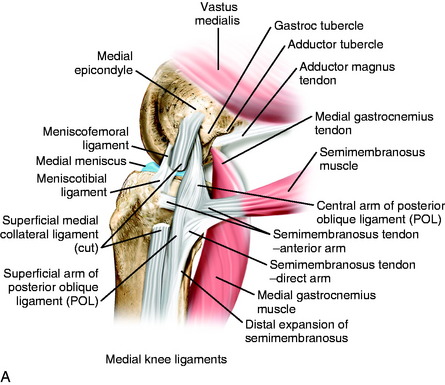

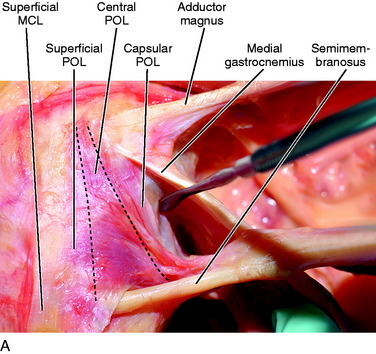

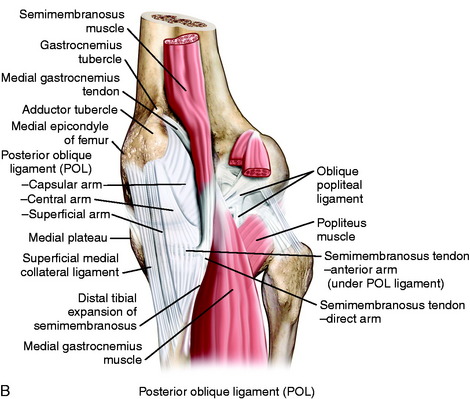

Layer 2: SMCL and Posterior Oblique Ligament

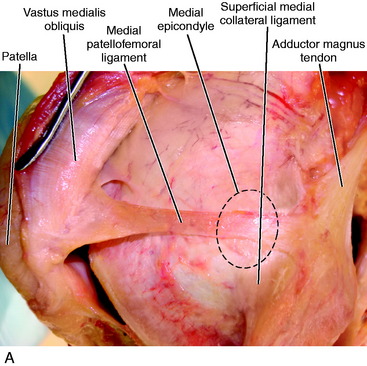

The SMCL is a well-defined structure that spans the medial joint line from the femur to tibia. According to LaPrade and coworkers,28 the SMCL does not attach directly to the medial epicondyle of the femur, but is centered in a depression 4.8 mm posterior and 3.2 mm proximal to the medial epicondyle center. Other studies have described the MCL attaching directly to the medial epicondyle of the femur.* The confusion lies in the confluence of fibers that reside in the area of the medial epicondyle that make it difficult to identify the precise attachment site of the SMCL. As shown in Figure 1-3, the authors agree with LaPrade and coworkers28 that the main fibers of the SMCL attach to an area just posterior and proximal to the medial epicondyle; but the origin of the SMCL is rather broad and, thus, there are also superficial fibrous strands attaching anterior on the medial epicondyle and posterior in a depression on the medial femoral condyle.

FIGURE 1-3 A, Osseous landmarks of the knee (medial view). B, Soft tissue attachments to bone (medial knee).

The posterior fibers of the SMCL overlying the medial joint line, both above and below the joint, change orientation from vertical to a more oblique pattern that forms a triangular structure with its apex posterior,4,30 eventually blending with the fibers of the posterior oblique ligament (POL; Fig. 1-4). LaPrade and coworkers28 described two anatomic attachment sites of the SMCL on the tibia. The first is located proximally at the medial joint line and consists mainly of soft tissue connections over the anterior arm of the semimembranosus. The second attachment site is further distal on the tibia, attaching directly to bone an average of 61.2 mm from the medial joint line. In the authors’ experience, there is a consistent attachment of the proximal portion of the SMCL to the soft tissues surrounding the anterior arm of the semimembranosus, but a discrete attachment to bone is found only distally (see Fig. 1-4).

The gracilis and semitendinosus lie between layers 1 and 2 at the knee joint. The sartorius drapes across the anterior thigh and into the medial aspect of the knee invested in the sartorial fascia in layer 1. The insertion of the sartorius, as described by Warren and Marshall,46 consists of a network of fascial fibers connecting to bone on the medial side of the tibia, but does not appear to have a distinct tendon of insertion such as the underlying gracilis and semitendinosus. However, LaPrade and coworkers28 located the gracilis and semitendinosus tendons on the deep surface of the superficial fascial layer, with each of the three tendons attaching in a linear orientation at the lateral edge of the pes anserine bursa.

In the authors’ experience, the sartorial fascia has a broad insertion onto the anteromedial border of the tibia and, with sharp dissection at its insertion, the underlying distinct tendons of the gracilis and semitendinosus are easily visualized (see Fig. 1-2). At the level of the joint, layers 1 and 2 are easily separated from each other over the SMCL. However, farther anteriorly, layer 1 blends with the anterior part of layer 2 along a vertical line 1 to 2 cm anterior to the SMCL.46

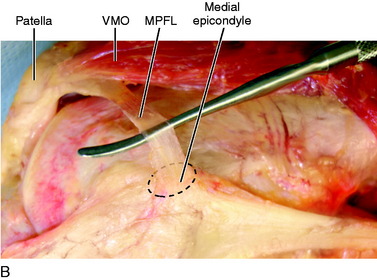

Also within layer 2 is the MPFL that courses from the medial femoral condyle to its attachment onto the medial border of the patella. This is a flat, fan-shaped structure that is larger at its patellar attachment than at its femoral origin, with a length averaging 58.3 mm (47.2–70.0 mm).38 Controversy exists regarding where the MPFL attaches at the medial femoral condyle. LaPrade and coworkers28 noted that the MPFL attaches primarily to soft tissues between the attachments of the adductor magnus tendon and the SMCL, with an attachment to bone 10.6 mm proximal and 8.8 mm posterior to the medial epicondyle. Steensen and associates,40 from a dissection of 11 knees, believed the MPFL attaches along the entire length of the anterior aspect of the medial epicondyle. Smirk and Morris38 described a variable origination of the MPFL on the femur. In dissections of 25 cadavers, the MPFL attached solely to the posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle, approximately 1 cm distal to the adductor tubercle in 44% of specimens. The adductor tubercle was included in the origin in 4%, the adductor magnus tendon in 12%, the area posterior to the adductor magnus tendon in 20%, and a combination of these in 4%. In 16% of the specimens, the MPFL attached anterior to the medial epicondyle.

In the authors’ experience, the MPFL attaches in a depression posterior to the medial epicondyle and blends with the insertion of the SMCL (Fig. 1-5). The anterior attachment of the MPFL consists of both attachments to the undersurface of the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) and the proximal medial border of the patella. The work of Steensen and associates40 demonstrated that the VMO does not overlap the MPFL, with the exception in 3 of 11 knees in which only 5% of the width of the MPFL was deep to the VMO. However, LaPrade and coworkers28 reported that the distal border of the VMO attaches along the majority of the proximal edge of the MPFL before inserting onto the superomedial border of the patella. The midpoint of the MPFL attachment is located 41% of the length from the proximal tip of the patella along the total patellar length. The experience of the authors of this chapter is that the MPFL attaches to the proximal third of the patella, with the majority of the ligament connected to the distal portion of the VMO with fibrous bands (see Fig. 1-5).

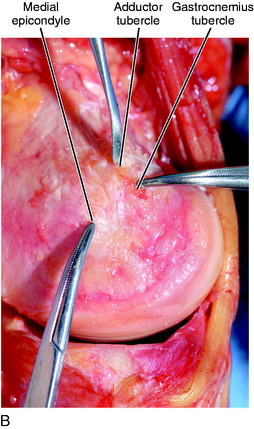

The adductor magnus and medial gastrocnemius tendons also contribute to the medial anatomy of the knee; both attach on the medial femoral condyle. Similar to the SMCL attachment, the confluence of fibers over the medial femoral condyle makes it difficult to precisely identify the exact location of each attachment (Fig. 1-6). The adductor magnus tendon is a well-defined structure attaching just superior and posterior to the medial epicondyle near the adductor tubercle. LaPrade and coworkers28 reported the adductor magnus does not attach directly to the adductor tubercle, but rather to a depression located an average of 3.0 mm posterior and 2.7 mm proximal to the adductor tubercle. The adductor magnus also has fascial attachments to the capsular portion of the POL and medial head of the gastrocnemius.

The medial gastrocnemius tendon inserts in a confluence of fibers in an area between the adductor magnus insertion and the insertion of the SMCL (Fig. 1-7A). LaPrade and coworkers28 described a gastrocnemius tubercle on the medial femoral condyle in this region; however, these authors stated that the tendon does not attach to the tubercle, but to a depression just proximal and posterior to the tubercle. In addition, fascial expansions from the lateral aspect of the medial gastrocnemius tendon form a confluence of fibers with the distal extent of the adductor magnus tendon in addition to the capsular arm of the POL (see Fig. 1-7A).

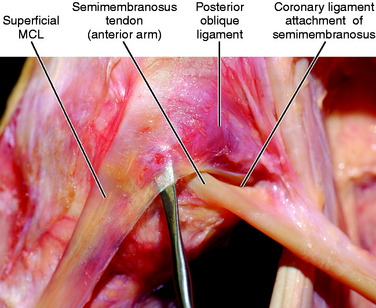

Layers 2 and 3 blend together in the posteromedial corner of the knee along with additional fibers that extend from the semimembranosus tendon and sheath that form the posteromedial capsule (see Fig. 1-7). LaPrade and coworkers28 used the term posterior oblique ligament (POL) for this same structure and described each of the three fascial attachments similar to Hughston and colleagues’ original description.21,22 The superficial arm of the POL runs parallel to both the more anterior SMCL and the more posterior distal expansion of the semimembranosus. Proximally, the superficial arm blends with the central arm; distally, it blends with the distal expansion of the semimembranosus as it attaches to the tibia.28

The central arm is the largest and thickest portion of the POL,28 running posterior to both the superficial arm of the POL and the SMCL. It courses from the distal portion of the semimembranosus and is a fascial reinforcement of the meniscofemoral and meniscotibial portions of the posteromedial capsule. LaPrade and coworkers28 noted that this structure has a thick attachment to the medial meniscus. As the central arm courses along the posteromedial aspect of the joint, it merges with the posterior fibers of the SMCL and can be differentiated from the SMCL by the different directions of the individual fibers. The distal attachment of the central arm is primarily to the posteromedial portion of the medial meniscus, the meniscotibial portion of the capsule, and the posteromedial tibia.28

The capsular portion of the POL is thinner than the other portions of this structure and fans out in the space between the central arm and the distal portions of the semimembranosus tendon. The capsular portion blends posteriorly with the posteromedial capsule of the knee and the medial aspect of the oblique popliteal ligament (OPL).28 It attaches proximally to the fibrous bands of the medial gastrocnemius tendon and fascial expansions of the adductor magnus tendon, with no osseous attachment identified.

The superficial portion of the POL is rather thin and appears to represent a confluence of fibers from the SMCL and the semimembranosus more distally. The capsular portion appears to represent a confluence of fibers from the semimembranosus, adductor magnus, and medial gastrocnemius (see Fig. 1-7). The central arm appears more robust, having contributions from the semimembranosus and medial gastrocnemius.

Controversy remains on whether three separate distinct anatomic structures make up the POL. Other authors36 have not found three distinct structures and note that with tibial rotation, different portions of the posteromedial capsule appear under tension but are not anatomically separate structures.

Semimembranosus

Controversy exists with respect to the exact number of attachments of the semimembranosus tendon at the knee joint.5,6,8,22,24,25,27,34,46 However, it appears that three major attachments have been consistently identified. The common semimembranosus tendon bifurcates into a direct and anterior arm just distal to the joint line. LaPrade and coworkers28,29 described the direct arm attaching to an osseous prominence called the tuberculum tendinis, approximately 11 mm distal to the joint line on the posteromedial aspect of the tibia. These authors also noted a minor attachment of the direct arm that extends to the medial coronary ligament along the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (see Fig. 1-4). A thinning of the capsule or capsular defect may be identified just distal to the femoral attachment of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and proximal to the direct arm of the semimembranosus. This is often the site of the formation of a Baker cyst.

Warren and Marshall46 believed the semimembranosus tendon sheath and not the tendon itself extends distally over the popliteus muscle and inserts directly into the posteromedial aspect of the tibia, with some fibers coalescing with SMCL fibers inserting in the same region. These authors contend that these fibers do not have functional significance, because no change was found in the position or tension of the MCL when those fibers were transected. LaPrade and associates29 separated the distal tibial expansion into a medial and a lateral division. Both divisions originating on the coronary ligament of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus are located on either side of the direct arm of the semimembranosus. The divisions then course distally to cover the posterior aspect of the popliteus muscle and insert onto the posteromedial aspect of the tibia, forming an inverted triangle. These authors noted that the medial division attaches just posterior to the SMCL, whose fibers coalesce with the superficial arm of the POL (as previously noted by Hughston and colleagues22) rather than the MCL.

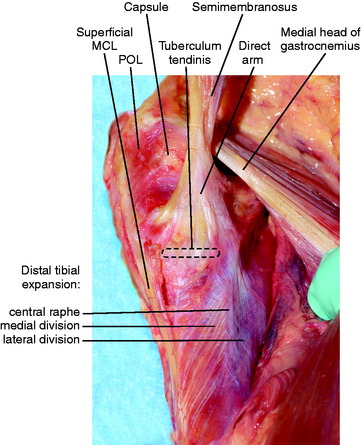

In the authors’ experience, as shown in Figure 1-8, the semimembranosus tendon sheath and not the tendon itself comprises the distal tibial expansion, which includes a medial and a lateral division with a central raphae separating the two. The anterior arm of the semimembranosus courses deep to the SMCL and attaches directly to bone just distal to the medial joint capsule on the tibia (Fig. 1-9). There are fibrous connections between the SMCL and the anterior arm of the semimembranosus, but only the anterior arm of the semimembranosus has an osseous attachment in this region. Because both the direct and the anterior arms of the semimembranosus anchor directly to bone and attach distal to the tibial margin of the medial joint capsule, these are not considered part of either layer 2 or layer 3 as described by Warren and Marshall.46

FIGURE 1-8 Distal tibial expansion of the semimembranosus tendon sheath with its medial and lateral divisions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree