This article discusses the sagittal gait patterns in children with spastic diplegia, with an emphasis on the knee, as well as the concept of the “dose” of surgery that is required to correct different gait pathologies. The authors list the various interventions in the order of their increasing dose. The concept of dose is useful in the consideration of the management of knee dysfunction.

The principal topographic patterns of involvement in cerebral palsy (CP) are spastic hemiplegia, spastic diplegia, and spastic quadriplegia. From the orthopedic surgeon’s point of view, it is convenient to think of the orthopedic priorities for each of these 3 main groups. In children with spastic hemiplegia, there is much more involvement of the foot and ankle than of the hip and knee. Orthopedic interventions usually address deformity of the foot and ankle, of which spastic equinus, equinovarus, and equinovalgus feet are the most common problems. On the opposite end of the severity spectrum, patients with spastic quadriplegia are more affected by deformities of the hip, pelvis, and spine. These deformities may preclude comfortable sitting. Deformities at the knee, foot, and ankle are often present and are sometimes significant, but spastic hip dislocation, pelvic obliquity, and scoliosis dominate orthopedic priorities.

In the lower limbs of children with spastic diplegia there is multilevel involvement, with the common pattern being equinovalgus at the foot/ankle, flexion with stiffness at the knee, and flexion with internal rotation at the hip. Contractures of the biarticular muscles, such as the hamstrings, rectus femoris, and gastrocnemius, create a challenge in selecting the most appropriate interventions to achieving sagittal plane balance. For example, hamstring lengthening may improve knee extension but at the expense of causing increased anterior pelvic tilt. A wide range of interventions has been described to manage knee dysfunction, but the indications and outcomes are not clearly established. Selber and colleagues introduced the concept of surgical dose in CP, whereby the surgical intervention should match the severity of dysfunction. The authors apply this concept to the management of knee dysfunction in children with CP, with a special emphasis on spastic diplegia. Some of these principles may be applied in children with hemiplegia and quadriplegia.

Evaluation

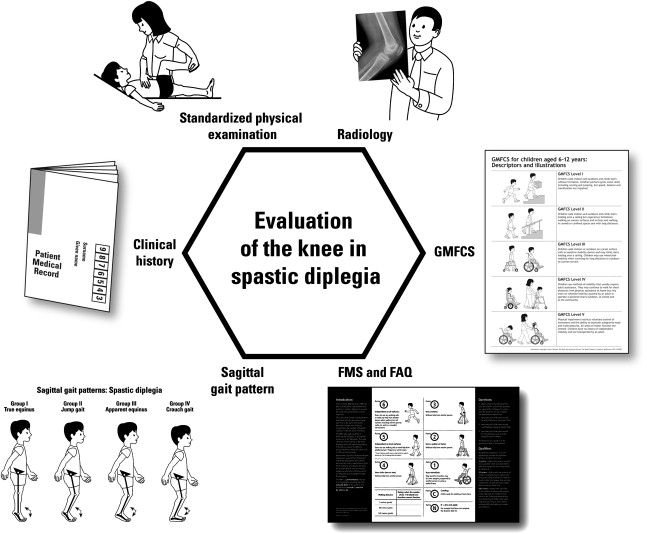

For a complete evaluation of the child with spastic diplegia, information from several sources needs to be gathered and synthesized. Formalized by Davids and colleagues in the diagnostic matrix, information is gathered from the following 5 sources ( Fig. 1 ):

- 1.

Clinical history

- 2.

Physical examination

- 3.

Instrumented gait analysis

- 4.

Special investigations including radiology

- 5.

Examination under anesthesia.