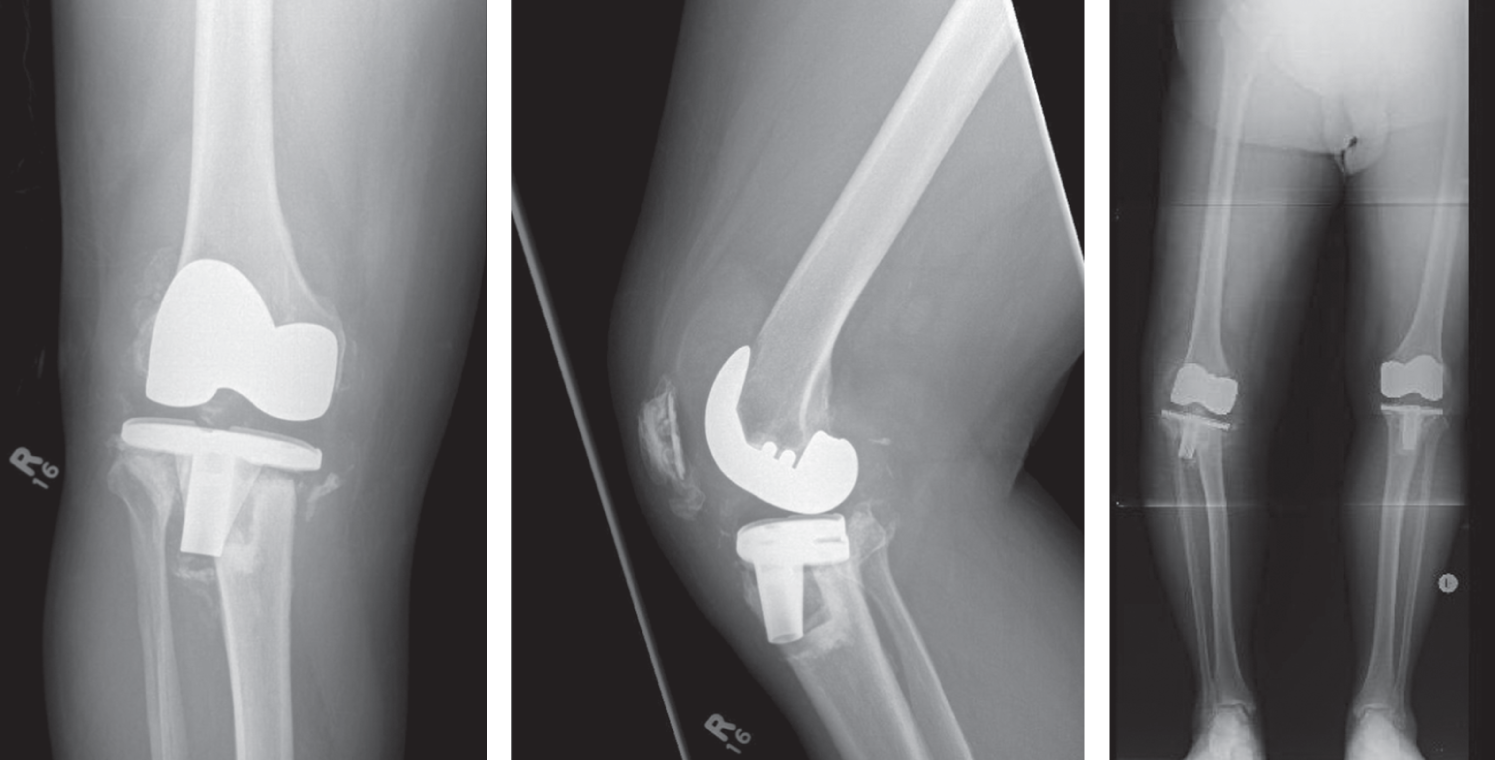

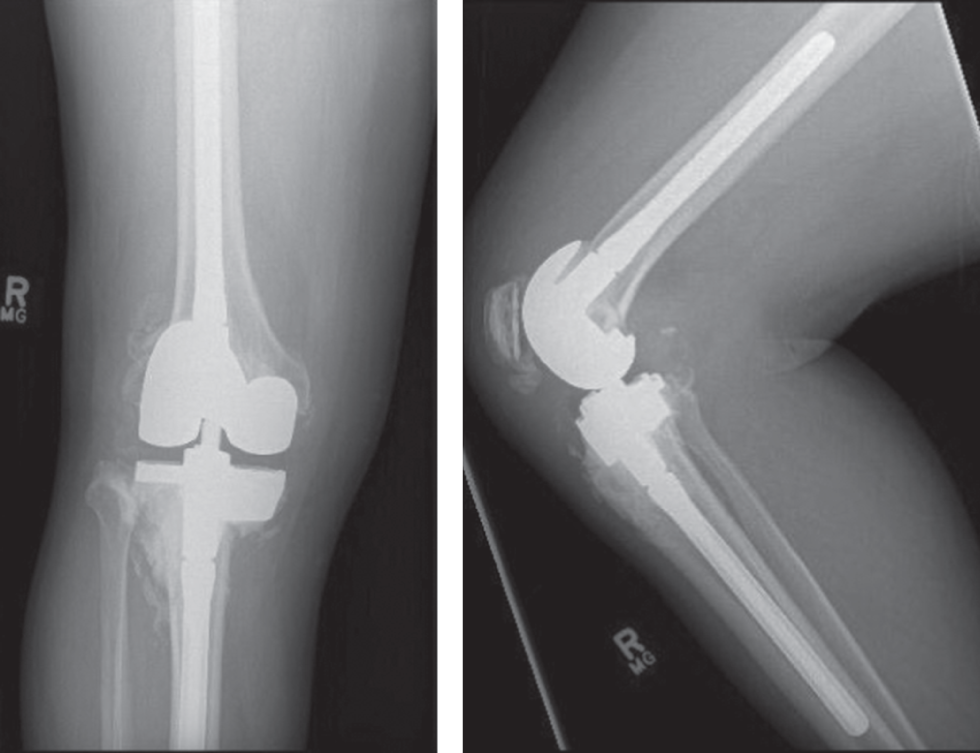

Sebastián León MD1, Jennifer Leighton MD FRCSC2, Xin Y. Mei MD2 and Paul R. Kuzyk MD MASc FRCSC2 1Hospital San José, Santiago, Chile 2Mount Sinai Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 3Division of Orthopaedic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada Current recommendations are that cement‐filling techniques be limited to defects <5 mm in depth, and that larger defects be treated with structural augmentation. However, recent evidence suggests that cement may be appropriate in larger defects.1 In planning for any revision TKA, one must estimate the amount of bone loss. Defects are identified and classified using radiographs and computed tomography (CT). The Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute (AORI) classification is most commonly use.2 Type 1 defects are minor, contained, with intact cortical bone, and the component sits above the level of the fibular head. Type 2 defects represent considerable loss of cancellous bone and the component sits at or below the proximal fibular head. Type 3 defects have a deficient metaphyseal segment, with possible compromise of ligament or tendon insertions. Figure 58.1 Preoperative radiographs. Figure 58.2 Postoperative radiographs. AORI‐1 defects <5 mm in depth have classically been treated using cement or morselized allograft. More recently, AORI‐2A defects <20 mm in depth and involving <50% of either plateau have been treated by cement‐fill alone.1 Biomechanical studies comparing cement with metal augments show superiority of metal augments in wedge‐shaped defects.3 However, when converted to a step‐cut pattern, cement is comparable to metal augments in resisting axial load.4 Several studies have reported good results using cement in uncontained defects.1,5–7 This is an economical way to manage select bone defects. Alternatively, modular augmentation allows the surgeon to create a “custom” implant and re‐establish the normal joint line. Blocks range in size from 5 to 25 mm, and are fixed to the tibial tray. These are often indicated in AORI‐2 defects of >25% of cortical bone, or if >40% of the base plate is unsupported by host bone.8 Uncontained defects of 20–45 mm can be managed with metal augmentation and a thick polyethylene liner. Larger defects are unsuitable for block augmentation alone, as this places the base plate too distally.9 In these scenarios, additional diaphyseal fixation using stemmed tibial components is typically needed to offload the metaphyseal augmentation and protect the cement–implant interface from failure.10 Cement fixation is inexpensive, readily available, and versatile due to its ability to readily fit and fill the size and shape of the bone defect. Bone cement should be vacuum‐mixed to reduce its porosity. The tibia should be cleaned using pulsatile lavage and dried with clean sponges to reduce cement lamination secondary to blood and tissue debris. Some authors have recommended using 3.5 mm drill holes in patients with sclerotic bone to enhance cement penetration and increase surface contact.11 The routine use of antibiotic‐laden bone cement in revision total joint arthroplasty is well supported by the literature.12 Berend et al. investigated the use of screws and cement for large tibial bone defects in primary TKA.13 Screws should be sunk into the cement enough to avoid contact between their heads and the implant. The authors report a 20‐year survival probability of 98.97 and 93.39% with screws and cement versus cement alone, respectively. Defects treated with screws were significantly worse than those without (p <0.0001), ranging from 5 to 30 mm in depth. Berend et al. also reported on 609 revision procedures at 17 years’ follow‐up.14 Of these, 264 had tibial defects >5 mm. Survival was 98.59 and 98.48%, when a defect was managed using cement with screws and without, respectively. Screws were, again, used in more severe defects (p <0.0001). When primary prostheses were used, there was a trend toward a higher revision rate, though statistical significance was not reached (4.2% vs 1.2%, p >0.05). Patel et al. prospectively looked at 79 knees with AORI‐2 defects treated with metal augments and stemmed prostheses.18 Mean follow‐up was seven years. They found nonprogressive radiolucent lines around 14% of augments, but no correlation with implant survival. They reported 92% survival at 11 years. Hass et al. reported 83% survival of tibial wedges at eight years.15 Panni et al. reported on 38 revision TKA with AORI‐2 and ‐3 defects treated with modular augments (blocks: 46 femoral, 38 tibial blocks; wedges: 2 tibial; TM cones: 5 tibial, 4 femoral).17 Three patients (7.9%) required reoperation, none due to loosening (2 infections, 1 instability). They noted two cases of nonprogressive radiolucent lines around the medial tibia, without platform subsidence. Hockman et al. reported on 54 revision TKA, using non‐modular trays with porous metal wedges.16 Interestingly, 17 knees failed and 59% of these had only moderate defects. These were revised with metal augmentation alone. IBG has been shown to be a viable option in treating bone loss in revision THA. Its use in revision TKA remains controversial. IBG was first described by Hastings and Parker,19 and later standardized by Sloof et al. for the treatment of large acetabular defects in THA.20 Its successful use in the hip led to its use in knee revision, 21–23 as first described by Ullmark and Hovelius.24 IBG restores bone stock, filling irregular defects without need for further bone removal.25

58

Management of Structural Defects in Revision Knee Arthroplasty: Tibial Side

Clinical scenario

Top three questions

Question 1: In patients with moderate tibial bone loss at revision TKA, are porous metal block augments a better option for implant survival compared to cement filling?

Rationale

Clinical comment

Available literature and quality of the evidence

Findings

Resolution of clinical scenario

Question 2: In patients with moderate to severe tibial bone loss at revision TKA, is impaction bone grafting (IBG), compared to other options, a viable technique in terms of survival – specifically aseptic loosening?

Rationale

Clinical comment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree