Management of On-site Emergencies

Brent S.E. Rich

Benjamin B. Betteridge

Spencer E. Richards

EMERGENCIES!!! By the very nature of the word, these are events that are “unexpected.” Although unexpected, they should not be unanticipated. Anticipation of potential emergencies is the responsibility of the Sports Medicine Team. Preseason and preparticipation preparation is the time to identify the potential emergencies that may affect the involved sport and to plan accordingly. Although crippling or fatal events in sports are rare, this does not lessen the need for preparation and development of an emergency action plan.

Initial evaluation and triage is the first principle in emergency treatment. Rapid recognition will determine the need for either emergency response or routine management. Often, this initial management decides the ultimate outcome. If the Sports Medicine Team rehearses roles and responsibilities, it will go a long way to develop comfort and control in the chaotic moments of an emergency.

Included in the preparation for emergencies is the development of specific written emergency protocols. These include roles and responsibilities of the various members of the Sports Medicine Team, obtaining contact numbers for each member, and understanding how to mobilize the Emergency Medical System (EMS) in your area. Working with the local EMS providers and emergency room staffs in standardizing protocols is crucial to the systematic management of emergencies in sport. We must be cautious not to assume that emergency procedures will go smoothly when the time arises, but foresee and minimize the potential logistical problems that may impair proper treatment.

In this chapter, initial evaluation of the collapsed athlete will be presented, followed by a review of on-site emergencies from an organ system perspective (i.e., head and neck, musculoskeletal, cardiac, respiratory) and a discussion of life-threatening heat stroke. Additional non-emergent conditions in each of these areas will be reviewed in more detail in subsequent chapters. Finally, an outline for an emergency action plan will be presented.

On-Site Management of the Collapsed Athlete

The purpose of being an on-site or sideline member of the Sports Medicine team is to witness the mechanism of injury or trauma and implement the appropriate management steps. Was contact or collision involved in the collapse? Did the collapse occur during activity or after the play was over? Does this emergency require additional providers or transport to appropriately manage the event?

The on-site physician is responsible for the management of the athletic contest, although the athletic trainer is often the first person to triage and interact with the downed athlete. If the team physician is absent, the athletic trainer or the most qualified person present takes charge of the emergency. Mobilization of the EMS system by dialing 911 may be necessitated based on the situation. The initial evaluation includes a primary and secondary ABCD survey and can be done within the first few seconds of arriving on the scene. Stopping play and removing the athlete or other participants from ongoing danger is the next immediate responsibility.

The Primary Survey is performed quickly and in the following order:

Level of responsiveness (AVPU)

A = alert

V = responds to verbal stimuli

P = responds to painful stimuli

U = unresponsive

If the patient is unresponsive, call for help or call 911

A = Airway

B = Breathing

C = Circulation

For a cardiopulmonary emergency, the fifth step is D = Defibrillation

E = Exposure

The Secondary Survey includes the following:

A = Advanced airway

B = Breathing

C = Circulation

D = Differential diagnosis

TABLE 10.1 Summary of BLS Abcd Maneuvers for Infants, Children, and Adults | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Primary Abcd Survey

The initial assessment must follow an organized system of review. The ABCD mnemonic is the recommended triage assessment tool. (The 2005 Revised basic life support [BLS] guidelines are provided in Table 10.1)

Airway and Cervical Spine

Look and listen for spontaneous breathing. If the patient is face-down and spontaneous breathing cannot be assessed, logroll the patient onto his/her back while immobilizing the cervical spine by gentle in-line traction. Competent assistance is crucial to keep the head and neck in proper alignment. If the neck is not in line with the body, gentle traction should be instituted to place in a neutral position. If this increases pain or causes neurological or circulatory compromise or resistance is detected, maintaining in the position found is acceptable until hospital evaluation. Exceptions are in the inability to establish an airway.

Establish airway access. If necessary, remove the face mask using appropriate tools. Be careful not to disrupt the neck.

Institute the head-tilt, chin-lift, or jaw-thrust maneuver. These maneuvers open the airway. The jaw-thrust maneuver is the safest method inasmuch as it does

not involve extending the neck, and is the preferred method if a cervical spine injury is suspected.

Clear the airway. Observation and removal of foreign matter or the mouthpiece with a finger sweep or suction device may be necessary if it is obstructing the airway.

If a clear and unobstructed airway is not accomplished by the jaw thrust, insert a nasal or oral airway. An oral airway should only be used in the unconscious person.

Supplemental oxygen may be used with or without an airway in place.

Process in Suspected Cervical Spine Injury

In an unconscious or altered conscious patient, a cervical spine injury must be assumed.

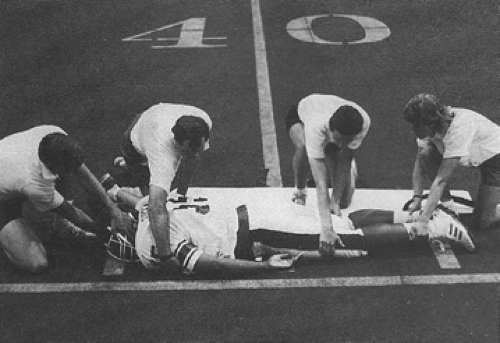

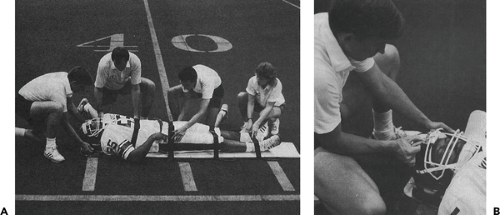

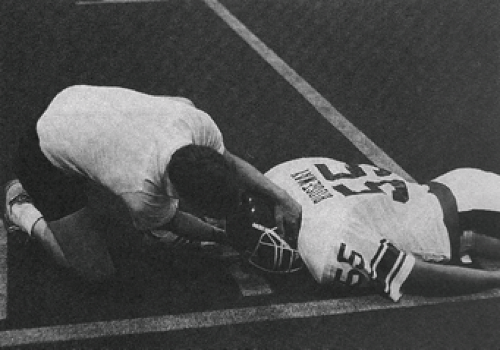

The head and neck must be maintained in a neutral position with slight in-line traction. Initial on-field evaluation requires one rescuer to maintain neck stabilization until the patient is adequately secured to a spine board.

Removal of the helmet is not recommended on the field of play.

The use of ammonia capsules or sudden movement is contraindicated in the unconscious patient.

Please see diagrams demonstrating the appropriate management of an athlete (see Figures 10.1, 10.2, 10.3).

Breathing

Place the side of your face directly over the patient’s mouth and nose, looking down the body axis. Look, listen, and feel for normal breathing by observing the rise and fall of the chest for 5 to 10 seconds, and feel for air movement. Estimate the respiratory rate.

Note signs of difficulty in breathing (pursed lip breathing, nasal flaring, retractions, leaning forward, used of accessory muscles, etc.). Observe the rhythm of respiration—prolonged inspiration suggesting upper airway obstruction or prolonged expiration suggesting lower airway obstruction. Listen for air movement (stridor, wheezing, snoring, gurgling, etc.).

Look in the mouth for a foreign object, if you see one, remove it with a finger sweep.

If breathing is absent, inflate the lungs with two slow breaths. Each breath should last approximately 2 seconds.

If after the airway is secured there are no spontaneous respirations, artificial ventilation is necessary. These methods include (a) mouth to mask, (b) bag-valve to mask, and (c) mouth to mouth.

Suction may be necessary if the patient vomits. Requirement of an appropriate suction device must be anticipated. Suction should be no longer than 15 seconds at a time. Logroll with the cervical spine stabilized to minimize aspiration risk.

Figure 10.1 When an athlete has a suspected injury to the cervical spine, maintain the position of the head while checking for breathing |

Circulation

Assess for the presence of a pulse or other signs of circulation. In the emergency setting, feel for the carotid pulse to determine if the heart is beating. Check for circulation for 5 to 10 seconds. One can easily determine rate and regularity by palpation.

If the carotid pulse is present the systolic blood pressure is at least 60. If a radial pulse is present the systolic blood pressure is at least 80.

If circulation is present, but there is no normal breathing, rescue breaths should be applied at one breath every 6 to 8 seconds at a rate of 8 to 10/minute (1).

Defibrillation

In adult cardiac arrest, early defibrillation has the greatest impact on survival. Automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) operated by non-paramedics are easy to use. After the pads are applied to the sternum and left chest, the unit will recognize ventricular fibrillation if present and provide the appropriate shock as instructed by the AED.

Exposure

Inspect extremities and other body parts for fractures, bleeding, contusions, or evidence of deformity or disability.

Utilize a neurological grading system: the Glascow Coma Scale assesses eye opening, verbal, and motor responses. A score of less than 7 indicates coma (see Table 10.2).

Secondary Abcd Survey

Advanced Airway

Reassess the effectiveness of initial airway maneuvers and intervention.

Perform endotracheal intubation if indicated.

Breathing

Provide ventilation at 12 to 20 times/minute.

Confirm endotracheal tube placement (or other device) by at least two methods.

Provide positive pressure ventilation with 100% oxygen.

Circulation

Attach the patient to an electrocardiograph (ECG) monitor as soon as possible to allow continuous recording and reassessment of the cardiac rhythm.

Establish vascular access with the use of a large bore intravenous catheter and infuse with normal saline or lactated ringer’s solution.

Administer medications appropriate to the clinical situation or cardiac rhythm.

Differential Diagnosis

Determine the cause of the clinical situation.

TABLE 10.2 The Glascow Coma Scale | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

System Evaluation

The purpose behind system evaluation is to identify the conditions that may lead to death or significant morbidity. This list contains the most common conditions, but is not all-inclusive. Additional information will be presented in subsequent chapters.

Head and Neck

Head and cervical spine injuries are among the most devastating and frightening injuries that can occur in sport (2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree