Malignant Lymphoma of Bone

Parker and Jackson, in 1939, first described malignant lymphoma of bone and separated it from Ewing tumor. The discussion in this chapter is oriented to the problem of lymphoma of the skeleton as encountered by the surgical pathologist, the surgeon, and the therapist. Detailed considerations of lymphoma and leukemia are not appropriate here.

The term reticulum cell sarcoma is no longer used when referring to malignant lymphomas. Many lymphomas of bone show a mixture of cells rather than a pure growth of “reticulum” cells. Various types of lymphomas and Hodgkin disease can also involve the skeleton. Hence, the term malignant lymphoma is preferred for the entire group. These tumors are morphologically similar to their lymph node counterparts, but lymphoma of skeleton may have some unusual histologic features.

When malignant lymphoma is responsible for an osseous lesion, one of three clinical situations may obtain. Careful study of the patient may show no evidence of distant disease, and the osseous lesion can be presumed to be the primary lesion. Currently, staging studies include a skeletal survey, a radioisotope bone scan, bone marrow examination, and a computed tomographic scan of the abdomen and chest to rule out lymph node involvement. Many patients in the Mayo Clinic series did not have complete staging. Hence, the staging assigned to many of the patients was somewhat arbitrary. Of the 905 patients in this series, 274 were considered to have primary lymphoma of bone. In the series reported by Ostrowski and coauthors in 1986 involving 422 patients with malignant lymphomas evaluated at Mayo Clinic between 1907 and 1982, the tumors were considered to be primary in 179. The rest of the patients had more disease than a solitary bony focus. Furthermore, 82 patients had involvement of multiple skeletal sites with no apparent involvement of any other soft tissue. In the Mayo Clinic series, 308 patients were considered to have involvement of other soft-tissue sites such as lymph nodes, liver, or spleen, although these patients presented with skeletal disease. Staging studies disclosed disease in other sites. Lymphoma had been diagnosed in 123 patients before the skeletal biopsy was performed. For 156 patients, not enough information was available to stage the disease. Forty-four patients presented with a skeletal lesion that turned out to be a manifestation of leukemia. Of these, 22 were granulocytic sarcomas and 21 were lymphocytic leukemia. One patient had megakaryoblastic leukemia.

INCIDENCE

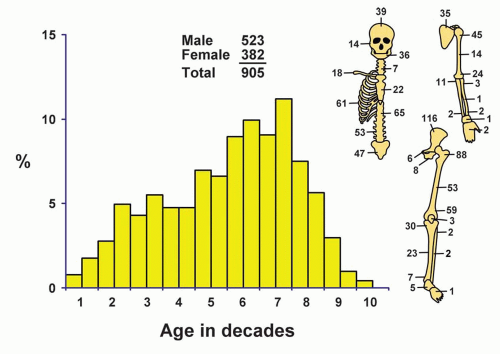

The 905 cases of malignant lymphoma comprised as 12.7% of the malignant tumors in this series. The 274 “primary” lesions in bone comprised only 3.9% (Fig. 17.1).

SEX

Males predominated at a ratio of 4 to 3 in both the primary and the total groups. This is in general agreement with what has been reported in the literature.

AGE

Malignant lymphoma can occur in a patient of any age but is rare in the very young. Seven patients were in the first 5 years of life and 16 in the second 5 years. Approximately 20% of the patients were in the sixth decade of life. The age distribution for those with presumably primary lesions in bone parallels that of the overall group.

LOCALIZATION

When a malignant lymphoma arises in certain specific sites, such as the maxillary antrum or along the spinal column, it is often impossible to prove an osseous origin. Many patients with involvement of the antrum and one or more of its bony walls are excluded from the series because an origin from bone could not be verified. Similarly, most surgical patients with lymphoma affecting the spinal cord or its emerging nerves are excluded because proof of osseous disease is not available. Most lymphomas involve the portion of the skeleton containing red marrow. It is very unusual to find lymphoma involving the small bones of the hands and feet. Five lesions involved the tarsals and one a phalanx of a toe, but none involved a metatarsal. A single lesion involved one of the carpal bones, and two patients presented with involvement of the metacarpal bones. There were no cases of the lesion involving the phalanges of the hand, although involvement of these bones was seen as part of a systemic process. The most common single site was the femur, followed by the ilium. The distribution of the cases of primary lesions was similar to that of the entire group.

SYMPTOMS

Pain, swelling, and subsequent disability are the cardinal features of any malignant tumor of bone, including lymphoma. Pain of variable intensity is practically a constant feature, and, occasionally, it has been present for several years, although ordinarily its duration is measured in months. Neurologic symptoms commonly occur when these tumors affect the spinal column. Many studies have emphasized that patients with even extensive solitary malignant lymphomas have an unexpected sense of well being, and absence of the general complaints so commonly associated with malignant disease. Pathologic fracture may be the presenting symptom. In one patient in the Mayo Clinic series, malignant lymphoma developed in a focus of old chronic osteomyelitis of the tibia. Another patient, a 94-year-old woman with lymphoma of the ilium, had radiographic evidence of Paget disease in multiple bones. Occasionally, patients present with lytic bone lesions and hypercalcemia suggesting hyperparathyroidism.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A mass in a tender or warm region may be the main finding and is often associated with disability of the affected part. Enlarged regional lymph nodes may be found. One should search for signs of disseminated malignant lymphoma, such as involvement of multiple bones, distant lymph nodes, and other soft-tissue structures. Because of the occasional similarity between tumefactions due to malignant lymphomas and those due to leukemia, it is important to study the peripheral blood of these patients.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

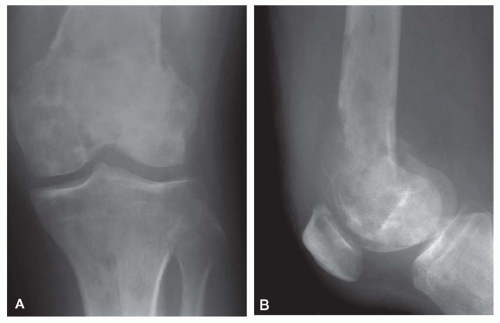

Radiographically, the lesion frequently is very extensive, often involving 25% to 50% of the affected bone and, in some cases, the entire bone. The lesion tends to

involve the mid portion of the bone. Bone destruction is the predominant feature of primary lymphoma. The areas of destruction give the bone a mottled and patchy appearance in many cases, and sometimes the outline of the bone is completely lost. Because of the infiltrative nature of the disease, the interface within adjacent normal bone is poorly defined. Approximately half of the patients in this series had evidence of some reactive proliferation of new bone that is not laid down by the tumor cells themselves. Hence, the typical appearance of malignant lymphoma can be considered to be that of an extensive lesion showing a mixture of lysis and sclerosis. Nearly every malignant lymphoma destroys cortical bone, and approximately 25% are associated with some thickening of the cortex. Often, soft-tissue extension of the tumors is obvious and large. In spite of the extensive involvement of the bone, including destruction of the cortex, periosteal new bone formation is uncommon. This is in contrast to the striking periosteal new bone formation seen in Ewing sarcoma. Approximately one-fourth of the patients have evidence of pathologic fracture (Figs. 17.2, 17.3 and 17.4).

involve the mid portion of the bone. Bone destruction is the predominant feature of primary lymphoma. The areas of destruction give the bone a mottled and patchy appearance in many cases, and sometimes the outline of the bone is completely lost. Because of the infiltrative nature of the disease, the interface within adjacent normal bone is poorly defined. Approximately half of the patients in this series had evidence of some reactive proliferation of new bone that is not laid down by the tumor cells themselves. Hence, the typical appearance of malignant lymphoma can be considered to be that of an extensive lesion showing a mixture of lysis and sclerosis. Nearly every malignant lymphoma destroys cortical bone, and approximately 25% are associated with some thickening of the cortex. Often, soft-tissue extension of the tumors is obvious and large. In spite of the extensive involvement of the bone, including destruction of the cortex, periosteal new bone formation is uncommon. This is in contrast to the striking periosteal new bone formation seen in Ewing sarcoma. Approximately one-fourth of the patients have evidence of pathologic fracture (Figs. 17.2, 17.3 and 17.4).

Irregular sclerosis of the affected site is sometimes a noticeable feature, and this finding adds to the confusion of malignant lymphoma with chronic osteomyelitis.

Disseminated malignant lymphomatous involvement of the skeleton may simulate osteoblastic metastatic carcinomatosis. Malignant lymphoma may involve multiple bones of the skeleton even in the absence of visceral and lymph node involvement. Sclerosis may precede the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma by several years and may even resemble Paget disease of the bone, especially in flat bones.

Disseminated malignant lymphomatous involvement of the skeleton may simulate osteoblastic metastatic carcinomatosis. Malignant lymphoma may involve multiple bones of the skeleton even in the absence of visceral and lymph node involvement. Sclerosis may precede the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma by several years and may even resemble Paget disease of the bone, especially in flat bones.

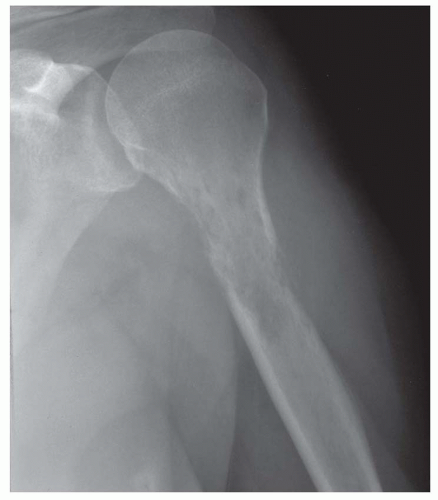

Figure 17.3. Permeative destructive lesion involving the proximal humerus in a 62-year-old woman. The histologic features were those of a myeloid sarcoma. |

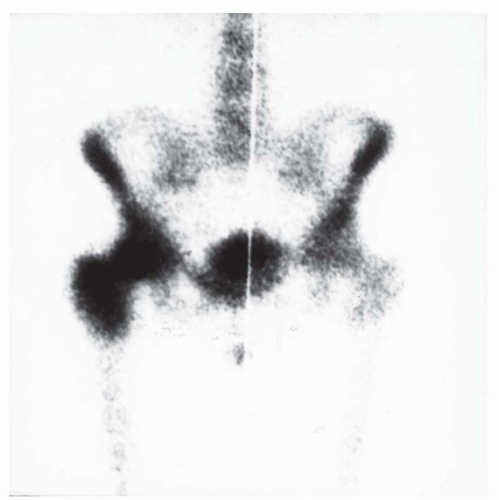

Figure 17.4. Hodgkin disease involving the ilium in a 51-year-old woman. There is increased sclerosis in the periacetabular region. |

When the disease is confined to the marrow cavity, there may not be enough destruction of bone to be identified visibly on plain radiographs. Radioisotope bone scans are considerably more sensitive in localizing skeletal involvement with lymphoma. A positive bone scan with a negative plain radiograph should suggest malignant lymphoma as one of the possibilities. Malignant lymphoma may also present as an abnormal marrow signal on magnetic resonance imaging or increased marrow density on computed tomograms, although the plain radiographs may be negative (Figs. 17.5 & 17.6).

Wilson and Pugh, who studied the Mayo Clinic series, concluded that the radiographic findings varied so much that they could not be regarded as characteristic. Although the radiologist frequently suspects the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma, other lesions, including metastatic carcinoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing tumor, eosinophilic granuloma, and chronic osteomyelitis, cannot always be excluded with certainty.

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

The gross features of primary malignant lymphoma of bone are not pathognomonic, but some of them are mentioned. Although any portion, and frequently a large part, of the long bone may be involved, the main mass of the tumor and its extraosseous extension, if present, are most often in or near the metadiaphyseal region. A variable amount of soft-tissue extension is practically always present by the time the diagnosis is made. The bone at the affected site is destroyed to a variable extent, and occasionally white areas of necrosis or zones of secondary sclerosis are seen. Residual osseous trabeculae are frequently admixed with tumor, imparting a firm and gritty consistency. When a malignant lymphoma extends into the soft tissues, it produces a soft tissue mass that is fleshy and simulates the appearance of malignant lymphoma involving lymph nodes. The margins of a malignant lymphoma in the bone, as well as in the adjacent soft tissues, are ordinarily indistinct. Regional lymph nodes may be involved, and, as indicated above, there may be gross pathologic evidence of disseminated malignant lymphoma (Figs. 17.7, 17.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree