Malignancy in Giant Cell Tumor of Bone

To be certain of the diagnosis of malignant giant cell tumor, the pathologist must demonstrate zones of typical benign giant cell tumor in the malignant neoplasm under appraisal or in previous tissue obtained from the same neoplasm. When confronted with an obviously malignant growth that contains a few or many benign osteoclast-like giant cells, the pathologist can prove a relationship to benign giant cell tumor in no other way because other neoplasms of bone, including many of the osteosarcomas, contain a scattering or many of these benign giant cells. Even classic low-grade parosteal osteosarcoma can recur as a highly malignant sarcoma with such an abundance of benign giant cells that, without reference to the original neoplasm, the recurrent lesion may be mistaken for a malignancy in giant cell tumor. Some of the osteosarcomas of soft-tissue origin also contain numerous benign giant cells but obviously bear no relation to giant cell tumor of bone. For any given neoplasm, the stromal cells, not the benign multinucleated cells, must determine its classification. In 1960, Troup and coworkers provided clinicopathologic correlations to support this view.

With this strict definition of malignant giant cell tumor, 39 examples were found in the Mayo Clinic files. Of these, 34 were judged to occur after treatment of typical benign giant cell tumors—tumors that contained no features differentiating them from the rest of the giant cell tumors. These are referred to as secondary malignant giant cell tumors. Of the 34 cases, 26 occurred after treatment of a benign giant cell tumor which had included radiation. The other eight tumors occurred after surgical treatment of a giant cell tumor. In 6 of the 34 cases, the clinical features suggested that the original diagnosis was giant cell tumor, although this material has not been reviewed at Mayo Clinic. The interval from the diagnosis of giant cell tumor to the diagnosis of sarcoma varied from 1 to 42 years. In only one case was residual giant cell tumor present at the time the sarcoma was diagnosed. The other five primary tumors contained foci of sarcoma along with a giant cell tumor at the time of diagnosis.

Evidence is increasing that radiation may trigger the malignant transformation of various osseous lesions, especially giant cell tumor. As indicated above, however, radiation was not implicated in 13 of the 39 tumors.

Analysis of the literature on malignant giant cell tumor is virtually impossible because of lack of strict definition. The subject is further clouded by the finding of an extremely rare benign metastasizing giant cell tumor. As indicated in the preceding chapter, 20 of the 671 benign giant cell tumors produced pulmonary metastasis.

INCIDENCE

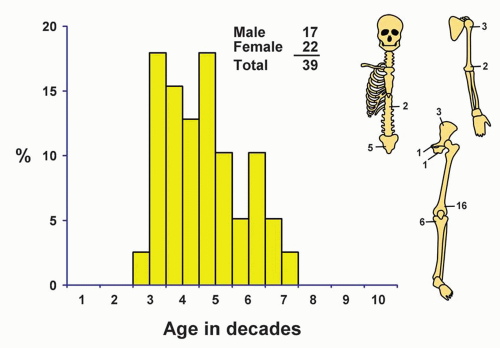

The malignant giant cell tumors comprised less than 0.55% of the total group of malignant tumors and 5.8% of all giant cell tumors (Fig. 20.1).

SEX

In this small group, there was a slight female predominance, slightly less than that seen in the overall giant cell tumor group.

AGE

Patients with malignant giant cell tumor were somewhat older, on average, than those with benign giant cell tumor. This difference is explained at least partly by the fact that most of the tumors developed several years after treatment of the benign precursor.

LOCALIZATION

The distribution of these tumors is not significantly different from that of the benign giant cell tumors that do not undergo malignant transformation. The region of the knee joint, involving the distal femur and proximal tibia, accounted for more than half of the tumors.

SYMPTOMS

At onset, most of the patients had symptoms of ordinary benign giant cell tumor. Thirty-four of the 39 tumors occurred an average of 12.85 years after the histologic diagnosis of giant cell tumor and 26 had been irradiated. The longest interval between the diagnosis of giant cell tumor and the development of sarcoma in the same area was 42 years. The five patients whose giant cell tumors contained malignant foci at the original operation had had preoperative pain the the region for 3 months and for 1, 1, 2, and 8 years. The fifth patient had a fracture in the area.

When the originally benign giant cell tumors became sarcomas, the clinical features changed abruptly from those of slowly progressing or quiescent giant cell tumors to those of the rapidly growing sarcomas they had become.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The physical examination findings are likely to be the same as those seen with any malignant tumor of bone. Cutaneous changes from previous radiation are common and may prompt the physician to elicit the history of such therapy.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree