3 Maggots and Wound Healing

History of Maggot Therapy

Fig. 10 Woodcut from Hortus Sanitatis, 1491.

My body is covered with worms and scabs,

My skin is broken and festering.

(Old Testament, Job 7:5, NIV Version, 1984)

The benefical effects of maggots on wounds have been recognized for centuries. Australian Aborigines used maggots to clean wounds for thousands of years. Military physicians stationed in Burma during World War II observed the medical use of maggots by the local residents. The Burmese traditionally placed maggots in wounds and covered them with mud and wet grass. Historic records indicate that Mayan Indians wrapped wounds with cloths soaked in animal blood and dried in the sun. The pulsating activity of maggots was soon observed beneath the wound dressings.

Military surgeons frequently observed and described the benefits of maggots infesting the wounds of fallen soldiers. The best known accounts are those of the French military surgeon Ambroise Pare (1510-1590), who reported on the Battle of Saint Quentin (1557), and the French surgeon Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey (1766-1842), who described his observations treating Napoleon’s injured soldiers during an expedition to Egypt (1799).

Although his accounts tended to emphasize the negative, destructive nature of maggots, Ambroise Pare also described remarkably quick recoveries in his maggot-infested patients. However, Pare did not attribute this to the maggots, nor did he realize that the “worms” were, in fact, fly larvae. Like most of his contemporaries, Pare believed that maggots developed spontaneously as part of the putrefaction process of devitalized necrotic tissue.

Fig. 11 Ambroise Pare (1510-1590), described quick wound healing in maggot-infested soldiers.

Napoleon’s surgeon, Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, recognized that “blue fly” maggots only removed dead tissue, after observing their beneficial effects on wounds. Larrey and his medical staff attempted to convince the soldiers that the maggots had a beneficial effect on the wounds, removing necrotic tissue and accelerating the natural healing process.

The American Civil War

John Forney Zacharias (1837-1901), a Confederate army surgeon during the American Civil War, was probably the first physician to intentionally expose festering wounds to maggots. According to Chernin (1986), Zacharias wrote,

During this same time in the Northern hospitals, Union soldiers were having their wounds cleaned and dressed frequently, while the wounds of Confederate soldiers were left unkempt and maggot-borne. Reportedly, the flyblown wounds of the Confederate soldiers healed more quickly than those of the Union soldiers, and the Confederate soldiers were more likely to survive their wounds than were the Union soldiers.

William W. Keen (1837-1932), a Union army surgeon, noted the presence of maggots in wounds and commented that, in spite of their revolting appearance, the maggots evidently were not detrimental to the healing process (Goldstein, 1931). Still, the therapeutic application of maggots was hardly ever practiced by Union surgeons. The Confederate surgeons, on the other hand, often did not have any other choice since they rarely had enough dressing materials at their disposal (Adams, 1952). Joseph Jones (1833-1896), a Confederate doctor, wrote:

“I have frequently seen neglected wounds…filled with maggots… as far as my experience extends, these worms only destroy dead tissues and do not injure specifically the well parts.” {Cited after: Cunningham, 1970)

The germ theory put forward by Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur in the 1880’s revolutionized medicine in that it introduced the novel concept of hygiene-oriented practice, which forbade doctors to allow bacterially contaminated products to get anywhere near an open wound. Likewise, the development of antiseptic techniques completely reformed the field of surgery. Therefore, no physician practicing in the late 19th and early 20th century was willing to publicly propagate the idea of using unsterilized maggots.

World War I

William S. Baer, an American surgeon stationed in France during World War I, cared for two soldiers who lay injured on the battlefield for seven days before being discovered. By then, their wounds were teeming with maggots. Baer removed the maggots and observed, much to his surprise, that the wound beds were not filled with pus, but rather with healthy, newly formed granulation tissue. At that time, the mortality rate for soldiers similarly injured was 70 %. Baer recounts:

After the war, as a professor of orthopedic surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baer recalled his war experience while treating his many patients with chronic bone infections (osteomyelitis). He reared blowfly maggots, and applied them to the wounds of several patients. The foul smell of the wound disappeared along with the pus, and the symptoms of chronic inflammation subsided. All of these patients recovered and were discharged after just two months of treatment. To minimize the aversion of the patients and medical staff alike, and to keep the maggots from escaping, the physicians developed cage type dressings. To reduce the tickling sensation of the maggots moving around on healthy skin, Baer covered the sensitive edges of the wound.

Some of the patients developed gas gangrene and tetanus during the course of therapy. Although it could never be proven that the maggots were the cause of these infections, still Baer believed that sterile maggots should be used to prevent the spread of harmful micro-organisms.

Fig. 12 A series of different “maggot-dressings,” published 1934 in the journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. Type A was used in cases of osteitis of the jaw and other small wounds, type B was used for almost any wound, and type C was employed for very extensive wounds of the limbs (Fine & Alexander, 1934).

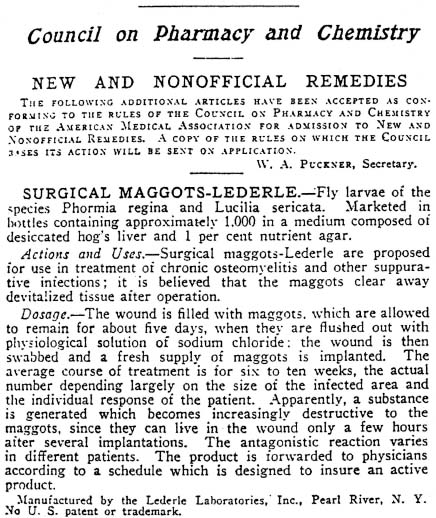

Baer died in 1931, but not before convincing many of his skeptical colleagues of the scientific and therapeutic value of his work. His results with maggot therapy were so dramatic that his research and therapy were continued by many in the US and Europe. Maggots were regularly used for wound care in more than 300 hospitals in the United States alone, and over 100 publications on the subject appeared in the medical literature between 1930 and 1940. The pharmaceutical company, Lederle Laboratories, produced sterile maggots commercially for those hospitals that did not have their own maggot-breeding facilities (in-sectaries).

Fig. 13 Advert for “Surgical Maggots-Lederle” as it appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 1932.

Penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928 but did not become commercially available until 1944. After that, the use of maggots in wound care rapidly declined and fell into oblivion, possibly due to the availability of antibiotic alternatives, to the decrease in prevalence of chronic infections, to the improved surgical techniques developed during World War II, or most likely to a combination of all three.

The “Revival” of Maggot Therapy Today

During the 1970’s and 1980’s, maggot therapy was used very infrequently, and only as a last resort for the most recalcitrant of infections (Horn 1976; Teich & Myers, 1986). In 1990, studies began to address the question: How does maggot therapy compare to other wound care methods currently in use? After all, why wait until everything else has been tried and has failed before using maggot therapy to treat a non-healing wound? The chance of cure is lessened by the very passage of time itself, so if maggot therapy is effective enough to use for the toughest of wounds, perhaps it should be used for less serious wounds, before they progress.

In a series of prospective and retrospective studies conducted between 1990 and 1995, it became apparent that maggot therapy was indeed more effective in debriding many non-healing wounds, and led to enhanced wound healing (Sherman et al., 1991,1993,1995; Sherman, 2002, 2003). Since then, the efficacy, simplicity, and low toxicity of maggot therapy has led to rapid acceptance by many wound therapists throughout the world. The International Biotherapy Society was founded in 1996 as a professional organization to advance the use, understanding, and acceptance of maggot therapy and other medical treatments that use live organisms. The first annual meeting of Biotherapists and Biotherapy research began that same year. In the United States, the non-profit Bio Therapeutics Education and Research (BeTER) Foundation now helps support patient care, education, and research in maggot therapy. By the year 2002, maggot debridement therapy (MDT) was again being used in over 2,000 health care centers world-wide. Having spent the past 50 years advancing their knowledge, skills, antibiotics, and surgical tools, medical practitioners have now invited therapeutic maggots back into the hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and bedrooms of the wounded.

How the Maggots Work

After several decades of study, it has become increasingly clear that the observed efficacy of maggot therapy in acute and chronic wound infection is not attributable to any single substance but, rather, to a combination of different factors acting in synergy. Applied to infected wounds the maggots have three modes of action:

• They debride (clean) the wounds,

• they kill micro-organisms, and

• they stimulate wound healing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree