Lunotriquetral Ligament Repair and Augmentation

Eric R. Wagner

Alexander Y. Shin

DEFINITION

Isolated injury of the lunotriquetral (LT) interosseous ligament complex is less common and less well understood compared with the other proximal row ligament injury, scapholunate (SL) dissociation.

LT ligament disruption can occur in isolation or in combination with other wrist pathology, such as a perilunate fracture or dislocation or a distal radius fracture.

It may result from acute trauma and chronic degenerative or inflammatory processes.

LT ligament injuries occur in a spectrum of severity ranging from partial tears with dynamic dysfunction (most common) to complete dissociation with static collapse.

Dynamic LT instability occurs when the ligament complex is intact but incompetent or attenuated, such as in the case of chronic or inflammatory degradation. Instability can occur in the absence of ligament dissociation (complete disruption).

LT dissociation occurs when the LT ligament is completely ruptured (both dorsal and volar portions ).

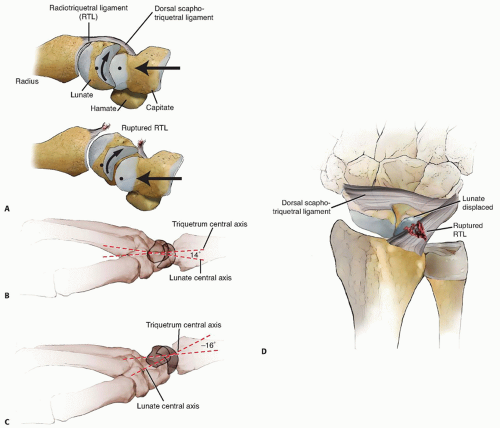

Static carpal collapse results when a complete disruption of the LT ligament is combined with an injury to the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament (and other secondary restraints). This results in volar flexion of the lunate in continuity with the scaphoid, termed volar intercalated segment instability (VISI). It is important to note that static VISI carpal collapse cannot be reproduced by simply sectioning the dorsal and palmar subregions of the LT ligament but also requires a loss of the radiotriquetral ligament (FIG 1).

ANATOMY AND KINEMATICS

Like the SL ligament, the LT interosseous ligament is C-shaped, spanning the dorsal, proximal, and palmar edges of the joint surfaces.

The palmar portion of the LT ligament is the thickest and most biomechanically important region of the entire complex, interweaving with the ulnocapitate ligament.18

In contrast, the dorsal component of the SL ligament has been shown to be the strongest.3

The dorsal LT ligament is important as a rotational constraint, whereas the palmar portion is the strongest and transmits the extension moment of the triquetrum as it engages the hamate.

The proximal region is composed of fibrocartilage, with little rotational or translational strength.

In the uninjured state, the lunate is “balanced” between the torques of the scaphoid and triquetrum. The scaphoid has a tendency to palmar flex, whereas the triquetrum has a tendency to extend. Through the LT and SL ligaments, these two forces are offset and the proximal carpal row is balanced around the lunate.

PATHOGENESIS

The exact mechanism of traumatic LT ligament injuries is not fully understood. Many mechanisms may play a role.

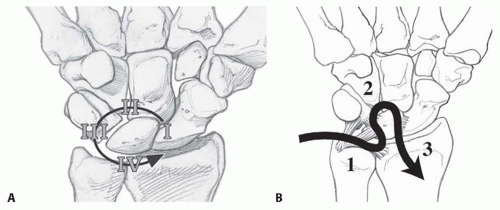

LT ligament injuries can occur in Mayfield III and IV perilunate injuries (FIG 2A).

Acute LT Injuries may result from a fall on a pronated wrist combined with either radial deviation or volar flexion.21

In the absence of trauma, degenerative LT instability can result from inflammatory arthritis or ulnocarpal impingement.15

Positive ulnar variance may lead to LT ligament degeneration by wear mechanisms or altered intercarpal kinematics (ulnar impaction syndrome).16

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of acute LT injuries has not been fully elucidated, but they may lead to degenerative joint changes.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

LT ligament injuries present as vague ulnar-sided wrist pain either acutely after trauma or as chronic wrist pain.21

The examination should encompass the entire wrist, focused on the ulnar side (Table 1).

Table 1 Perilunate and Reverse Perilunate Injury

Stage

Ligament or Bony Injury

Perilunate injury

1

SL ligament and long radiolunate disruption or scaphoid fracture

2

Volar capitolunate capsule tear in the space of Poirier

3

LT ligament dissociation

4

Dorsal radiolunate capsule tear and lunate subluxation

Reverse perilunate injury

1

Ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral

2

LT

3

Midcarpal joint and SL

Ulnar deviation with pronation and axial compression may elicit dynamic instability with a painful snap “catch up” clunk.

A palpable wrist click is occasionally significant, particularly if painful and occurring with radioulnar deviation.

Provocative tests that demonstrate LT laxity, crepitus, and pain are helpful to accurately localize the site of pathology. Three useful tests to perform include the following:

Ballottement17: The test is positive if increased anteroposterior (AP) laxity and pain occur.

Compression: Pain with this maneuver may indicate pathology of the LT or triquetral hamate joints.2

Shear test7: positive with pain, crepitance, and abnormal mobility of the LT joint

Other common findings on physical examination include limited range of motion and diminished grip strength.9

Comparison of findings with the contralateral wrist is essential.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs are often normal in LT ligament injuries because the most common presentation is dynamic dysfunction that manifests only with loading or certain positions of the wrist.

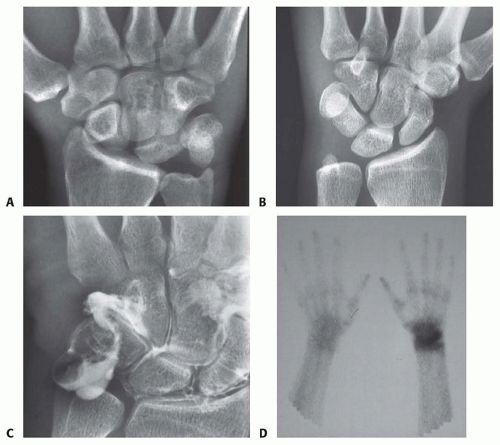

Dissociation of the LT ligament can lead to disruption of Gilula arcs I and II, demonstrating proximal translation of the triquetrum, with or without LT overlap (FIG 3A,B).

In contrast to SL tears, usually no LT gap occurs.

A static VISI deformity indicates not only LT ligament injury but also damage to the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament.

Additional helpful views include radial and unlar deviation view as well as the clenched-fist AP view. In these views, LT dissociation will manifest as a decrease in triquetral motion combined with an increase in the movement of the lunate, scaphoid, and distal row.2

Injection of local anesthetic into the midcarpal space can be useful to localize the cause of the patient’s pain.

Addition of corticosteroid to the injection may provide temporary relief by decreasing local inflammation and may serve as a positive prognostic sign for surgical treatment.

Arthrographic dye leakage through the LT interspace can indicate ligamentous injury (FIG 3C). However, correlation with the physical examination is necessary because age- dependent degenerative changes and asymptomatic LT instability have been reported.

Real-time videofluoroscopy can illustrate a “clunk” with ulnar deviation, as the triquetrum “catches up” when the wrist is moved into maximal ulnar deviation.

Technetium 99m diphosphate bone scan can localize an acute injury but is less specific than arthrography (FIG 3D).6

Magnetic resonance imaging is improving but is not yet reliable for imaging of LT ligament injuries.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of ulnar-sided wrist pain can be divided into six categories: osseous, ligamentous, tendinous, vascular, neurologic, and tumors.

Osseous injuries include the sequelae of fractures (ie, non-union or malunion) and degenerative processes. Fracture nonunions can affect the hamate, pisiform, triquetrum, base of the fifth metacarpal, ulnar styloid process, and distal part of the ulna or radius.

Degenerative processes involving the pisotriquetral joint, midcarpal (triquetrohamate) articulation, fifth carpometacarpal joint, or distal radioulnar joint. Ulnar impaction or abutment into the radius or carpus can contribute to these processes.

Ligamentous injuries include any of the ulnar-sided intrinsic (LT or capitohamate) or extrinsic (ulnolunate, triquetrocapitate, or triquetrohamate) ligaments as well as the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC).

Tendinopathy of the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) or flexor carpi ulnaris

Vascular lesions include ulnar artery thrombosis or hemangiomas.

Neurologic processes such as entrapment of the ulnar nerve in Guyon canal, neuritis of the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve, and complex regional pain syndromes

Although relatively rare, tumors include osteoid osteomas, chondroblastomas, and aneurysmal bone cysts.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Initial care for most LT ligament injuries is immobilization with a splint or cast with a pisiform lift to maintain optimal LT alignment. Initially, the wrist is immobilized for 4 weeks in a long-arm cast and then 4 additional weeks in a short-arm cast.

A pisiform lift involves molding a pad palmarly underneath the pisiform.

Nonoperative treatment is indicated for acute, stable injuries.

Immobilization may also improve symptoms associated with chronic injuries.

Midcarpal injections with local anesthetic and corticosteroid often provide significant relief for a prolonged time.

A trial of nonoperative treatment does not seem to jeopardize the outcome of subsequent surgical intervention.

Physical therapy targeting ECU strength and proprioception may help to stabilize the deforming forces in a LT tear.8

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Operative management is indicated in acute or chronic injuries unresponsive to conservative treatment.

The goal of surgery is to return rotational stability of the proximal carpal row and restore the natural alignment of the lunocapitate axis.

Functional reconstruction of the LT ligament can be accomplished with direct ligament repair, ligament reconstruction with a strip of ECU tendon graft, or arthrodesis.

The choice of intervention should be discussed with the patient. Our preference, based on outcomes studies performed at our institution, is tendon repair or reconstruction.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree