CHAPTER 10 Lower extremity assessment

1. Identify critical assessment parameters of the lower extremity physical assessment.

2. For each indicator used to assess perfusion, describe the techniques and results.

3. Identify two methods for describing lower extremity edema.

4. Compare and contrast assessment parameters indicative of lower extremity venous disease (LEVD) and lower extremity arterial disease (LEAD).

Chronic lower extremity ulcers are thought to affect from 0.5 to 1 million people in the United States at any given time (Bonham, 2003). Most of these wounds are chronic in nature, impact the individual’s quality of life, drain monetary and health care resources, and may even progress to possible limb loss if not managed appropriately. The key to successful management of any wound is an insightful assessment to determine the underlying cause so that treatment modalities address the pathologic factors. The etiologic factors of a lower extremity wound can be a myriad of diseases, infection, trauma, drugs, insect bites, pressure, or a combination thereof. Therefore, the wound specialist must be knowledgeable regarding clinical presentation and skilled in differential assessment. Critical assessment parameters are listed in Checklists 10-1 and 10-2 and described in this chapter.

CHECKLIST 10-2 Diagnostic Tests for the Lower Extremities

LEAD, Lower extremity arterial disease; LEVD, lower extremity venous disease.

General appearance of the limb

The wound specialist must become familiar with, and proficient in, using proper descriptive dermatologic terms to describe primary or secondary lesions, the pattern of distribution, and the arrangement of lesions or other abnormalities. Careful description often leads the examiner to a specific disease state. Limb appearance should be compared with that of the contralateral limb to identify or rule out trophic changes. With the patient’s shoes and socks off, the wound specialist should visually assess both extremities for varicosities, color, pigmentation, turgor, texture, dryness, fissures, hair distribution, calluses, abnormal nails, fungus, bunions, corns, bony deformities, and skin integrity. The web between the toes should be assessed for hygiene issues (Bonham and Kelechi, 2008).

Appearance of veins

The leg should be visually inspected or palpated for dilated veins, especially along the saphenous vein, beginning at the medial marginal vein on the dorsum of the foot and terminating at the femoral vein (about 3 cm below the inguinal ligament). Normally, healthy distended veins can only be visualized at the foot and ankle; the presence of dilated veins anywhere else on the leg may imply venous pathology and often is the first sign of venous insufficiency. Dilated veins, or varicose veins, are bluish, enlarged, and palpable. Often described as tortuous or rope-like, varicose veins are most often present on the back of the calf or on the inner aspect of the leg.

Skin color, shape, and integrity

The presence of any discoloration in the skin should be noted. For example, reddish-gray-brown hyperpigmentation in the gaiter region, more specifically hemosiderin staining (see Plate 34), is another skin color change that should be noted. Hemosiderin staining is hailed as the “classic” sign of LEVD, but it also can be found if significant trauma has occurred to the lower extremity. This type of discoloration develops after extravasated red blood cells break down and release the pigment hemosiderin.

Atrophie blanche, also seen with LEVD, is an atrophic, thin, smooth, white plaque with a hyperpigmented border, often “speckled” with tortuous vessels, occurring near the ankle or foot. Due to its scar-like appearance, atrophie blanche is easily and often mistaken for a previously healed ulcer (see Plate 35). Its presence is considered high risk for impending ulceration.

Tiny individual reddish-purple, nonblanching discolorations on the lower extremity may be observed. When the individual discolorations are larger than 0.5 cm, they are called purpura; when they are smaller than 0.5 cm they are called petechiae. Small blood vessels may leak under the skin and cause a blood or hemorrhagic patch that is a sign of some type of intravascular defect in individuals with normal or abnormal platelet counts. Purpura and petechiae (see Plates 36 and 37) are most often associated with LEAD (secondary to blood thinners) or vasculitis disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). Purpura associated with vasculitis disorders is referred to as palpable purpura. Purpura that occurs in the elderly due to fragility of the vessels is known as senile purpura.

Dermatitis (see Plate 38) manifested by scaling, crusting, weeping, excoriations (linear erosions due to scratching) from intense pruritus, erythema, or inflammation should be noted. Often these symptoms of dermatitis are misdiagnosed as cellulitis (see Table 12-3). Ulcers on the lower extremity should be noted in terms of their appearance, location, size, pain, and duration.

Edema (extent, pattern, distribution)

Edema is a localized or generalized abnormal accumulation of fluid in the tissues (WOCN Society, 2005). Numerous conditions can cause swelling of the lower extremity; examples include chronic venous disease, post phlebitis syndrome, iliac compression syndrome, lymphedema or lipedema, and systemic disease such as chronic heart failure, pulmonary hypertension and renal failure (Buczkowski et al, 2009). Edema causes swelling that may obscure the appearance of normal anatomy. To determine the presence of edema in the lower extremities, the appearance of one extremity should be compared with the other, noting the relative size and the prominence of veins, tendons, and bones. Edema is a significant finding in the examination of the lower extremity and should be investigated.

Extent.

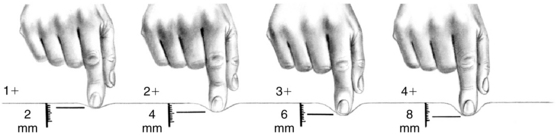

The extent of edema can also be assessed by pressing firmly but gently with the index finger for several seconds on the dorsum of each foot, behind each medial malleolus, and over the shins. Edema is “pitting” when there is a visible depression that does not rapidly refill and resume its original contour (Figure 10-1 and Box 10-1). Severity of edema can be categorized by either estimating the depth of the indentation (Figure 10-1) or the length of time for the indentation to resolve (Box 10-1). For clarity, the type of scale used should be recorded (e.g., 3+ pitting edema on a 4 point scale (Seidel et al, 2003).

FIGURE 10-1 Pitting edema may also be categorized by depth of depression.

(From Cannobio MM: Cardiovascular disorders, St. Louis, 1990, Mosby.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree