CHAPTER 5 Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

Historically, the functional role of the long head of the biceps tendon has been controversial. Viewpoints have ranged from the biceps’ being a critical structural restraint to superior migration of the humeral head, to its being a vestigial structure that has little if any functional role in the shoulder. More recently, the long head of the biceps has been implicated as a source of pain in patients with rotator cuff tears and in those with continued pain after shoulder arthroplasty performed for a proximal humeral fracture.1,2

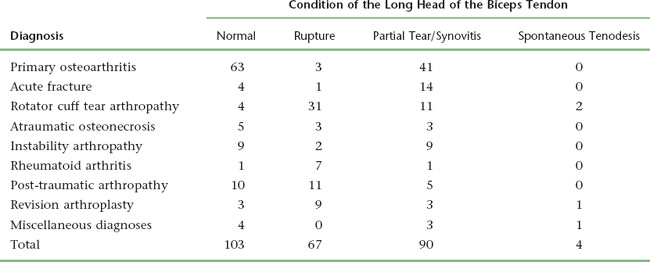

In our patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, we have noted gross abnormalities of the long head of the biceps tendon in 61%. Table 5-1 details bicipital abnormalities observed at the time of shoulder arthroplasty by diagnosis.

Table 5-1 CONDITION OF THE LONG HEAD OF THE BICEPS TENDON IN CASES OF SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY PERFORMED AT TEXAS ORTHOPEDIC HOSPITAL FROM 2003 TO 2005

Handling of the long head of the biceps tendon during shoulder arthroplasty has ranged from systematic preservation to systematic tenotomy or tenodesis regardless of its condition. In a series of 688 shoulder arthroplasties performed for primary osteoarthritis, concomitant biceps tenodesis or tenotomy was shown to improve outcomes. In this series, 121 shoulders underwent biceps tenodesis or tenotomy at the time of shoulder arthroplasty, independent of the condition of the biceps. These patients demonstrated a significantly higher postoperative mean activity score, mean mobility score, mean total Constant score, mean active anterior elevation, and mean active external rotation and better subjective results than did patients not undergoing concomitant biceps surgery.3 Fewer radiolucencies were reported around the glenoid component in shoulders that had undergone biceps tenotomy or tenodesis. Importantly, the incidence of complications was not affected by cutting the long head of the biceps tendon.

TECHNIQUE FOR HANDLING THE LONG HEAD OF THE BICEPS TENDON

The long head of the biceps tendon may be addressed any time it is visualized during shoulder arthroplasty. In most cases, we remove the intra-articular portion of the biceps just after preparation of the humerus and immediately before preparation of the glenoid because it is easily visualized at this junction of the procedure. Additionally, in some cases the long head of the biceps tendon may be contracted or lacks normal excursion. This could potentially hinder glenoid exposure, so the tendon is released before glenoid preparation. However, in fracture cases treated by hemiarthroplasty, the long head of the biceps tendon is left intact as an anatomic point of reference until just before fixation of the tuberosities.

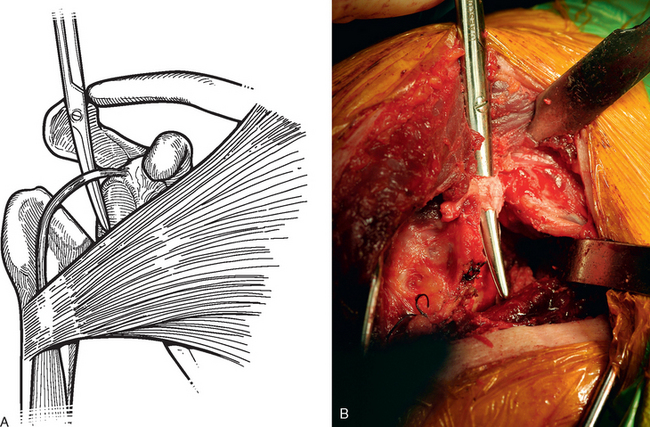

After humeral head resection and proximal humeral preparation, large curved Mayo scissors are placed superior and posterior to the long head of the biceps tendon to allow visualization of the tendon as it enters the bicipital groove (Fig. 5-1). A scalpel is used to transect the tendon at the entrance of the bicipital groove (Fig. 5-2). The tendon is pulled out of the bicipital groove inferiorly and sutured to the pectoralis major tendon with a figure-of-eight no. 1 nonabsorbable braided suture if tenodesis is to be performed (Fig. 5-3). Residual tendon is sharply removed to complete the tenodesis (Fig. 5-4). When the humeral head is retracted posteriorly for glenoid exposure, the remaining intra-articular stump of the long head of the biceps tendon is removed with Mayo scissors (Fig. 5-5). In cases of obvious tenosynovitis, any remaining bicipital sheath is removed as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree