Localized peripheral neuropathies

Anita Craig and James K. Richardson

Introduction

Localized peripheral neuropathies are even more common than generalized neuropathies and the two often coexist. Because a diffusely diseased peripheral nervous system is less able to recover from a mechanical insult than a healthy one, it is a clinical rule that a patient with generalized peripheral neuropathy is at an increased risk for specific discrete neuropathies. Localized neuropathies can also be a sequelae of a number of traumatic and iatrogenic injuries, which may or may not be immediately apparent upon initial evaluation and treatment of the injured patient. In addition, mechanical insults are particularly common in the rehabilitation setting as patients learn alternative strategies for self-care and mobility. Such strategies often involve stressing intact musculoskeletal regions to compensate for regions that are impaired, which increases the risk of nerve trauma in the intact regions. Early recognition, prevention and, when necessary, treatment of these specific neuropathies are critical for the prevention of further impairment and disability in older patients.

This chapter will be organized around typical (and nonspecific) symptoms and complaints. The potentially responsible focal neuropathy will be identified for each symptom. The details of clinical presentation and approach to each potentially responsible focal neuropathy will also be discussed.

Numb hand

Hand numbness and pain are extremely common complaints. Usually, one of the three nerves that serve the hand distally – the median, radial or ulnar nerves – is at fault. Hand numbness is also a possible presentation of a more proximal process such as a radiculopathy or plexopathy.

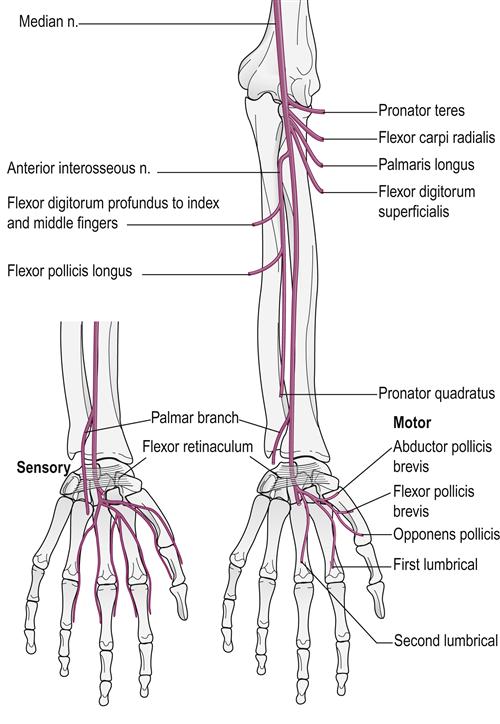

Median nerve compression

Median mononeuropathy at the wrist (CTS) demonstrates a bimodal age distribution, with peaks at ages 50–54 years and 75–84 years (Bland & Rudolfer, 2003). While older individuals tend to have more severe muscle loss and electrophysiologic changes than younger patients, there is no difference in the subjective symptoms reported (Blumenthal et al., 2006). This raises the concern that older patients are underreporting their symptoms. Although classic median nerve compression at the wrist (CTS) involves the second and third digits the patient often senses that the ‘whole hand is numb’. Usually the sensation in the thenar eminence will be spared as it is innervated by the palmar cutaneous branch which comes off proximal to the carpal tunnel and is thus spared. Pinprick sensitivity should be determined by first pricking a noninvolved area and then comparing the sensitivity between sides. Ask, ‘If this (the normal side) is 100 percent, how much is this (the affected side)?’ It is important not to ask the patient to indicate whether the sensation is sharp or dull because the sharp sensation is often maintained, even in the presence of a clinically significant localized or generalized neuropathy. An additional clue is the presence of Tinel’s sign, tingling that radiates from the percussed median nerve at the site of entrapment. The site of entrapment is more distal than is often perceived, approximately 1–2 cm beyond the distal wrist crease (Fig. 33.1). Phalen’s sign, in which the wrists are held in flexed positions for 30–60 seconds by pushing the dorsa of the hands together in front of the chest (Fig. 33.2) is often used in examination; however, it is overly sensitive because pain of a nature other than that caused by CTS is often elicited. A particularly misleading ‘positive’ Phalen’s test occurs when the hands turn numb because of the stretching of compressed ulnar nerves across the flexed elbows rather than because of median nerve compression at the wrist. Attention should also be paid to the muscles in the hand that are served by the median nerve, those of the thenar eminence. An obvious difference in bulk and strength suggests significant axonal damage to the median nerve and a prolonged, often incomplete, recovery, even with surgical decompression. It is important to test the strength of the patient’s thumb abductors by the examiner opposing them with their own.

Treatment

Treatment requires decreasing the pressure within the carpal tunnel. The pressure in the canal is increased in positions of hyperflexion or hyperextension. Avoidance of wrist extension and gripping is particularly difficult for those who use assistive devices such as walkers and canes. The temporary use of forearm platforms rather than hand grips on assistive devices lessens the pressure on the median nerve without compromising mobility and safety. The use of a splint, which prevents flexion and extension, particularly at night when a patient’s tendency is to sleep with the wrist flexed or extended, is recommended. Wrist splints are readily available in the community, however they frequently hold the wrist in greater than 30° of extension and may aggravate symptoms. The optimal extension angle is 0–5° and thus the brace may need to be modified, which can be easily done by bending the metal dorsal plate to a more appropriate angle. A patient who routinely uses a sliding board is also at risk. Using splints during transfers may allow continued function without repetitively compressing the median nerve. Local steroid injections may offer relief for those who do not respond to conservative measures. Injections have been shown to be superior to surgical decompression at 3 months, with significant clinical improvement in both nocturnal and diurnal symptoms and functional impairment. Two injections are usually required, administered 2 weeks apart (Ly-Pen et al., 2005). Injections can be very effective and associated with both improvements in symptoms and in electrophysiologic parameters (Aygul et al., 2005). Surgical decompression may be indicated with severe or rapidly progressive muscle loss, in the presence of a compressive mass, or after failure of conservative measures.

Ulnar nerve compression

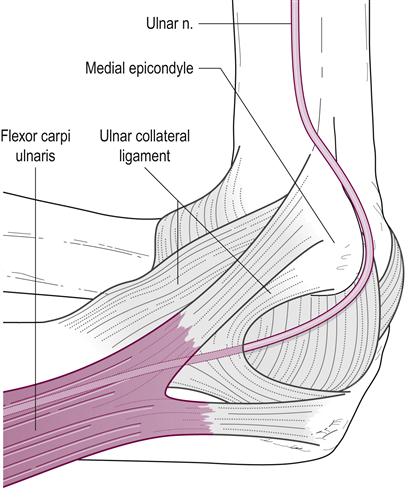

The second most common cause of hand numbness is ulnar nerve compression. This occurs most commonly at the elbow. Decreased pinprick response in the ulnar distribution (the fourth and fifth digits), hand-intrinsic muscle wasting and a positive Tinel’s sign over the ulnar nerve at the elbow are common findings. When it is severe, hand-intrinsic wasting leads to a characteristic hand position of hyperextension at the metacarpophalangeal joints and flexion at the interphalangeal joints. The interossei of the patient’s hands should be tested against the interossei of the examiner’s hands so that a true estimation of strength is possible. This is similar to the testing of the thumb abductors in CTS.

Cause and treatment

The cause of an ulnar neuropathy in an older patient is usually compression at the elbow within the groove between the olecranon and the medial epicondyle, or the stretching of the nerve from a prolonged hyperflexed elbow position (Fig. 33.3) (Kincaid, 1983). The latter often occurs while a patient sleeps on one side holding the hand against the neck and chest. Compression commonly occurs in wheelchair users as forearms and elbows rest on wheelchair arms. Men are more likely to develop ulnar mononeuropathies at the elbow (UME) and older age is associated with greater risk, as is a present or prior history of smoking (Richardson et al., 2009). This suggests that external compression may be more of a significant factor in the development of UME in women than in men. Treatment is best accomplished by protecting the elbow with an elastic pad, such as those often used by athletes. The pad can be maintained posteriorly during the day to prevent compression and anteriorly during sleep to prevent hyperflexion. If these measures are not successful, ulnar transposition surgery can be performed to remove the nerve from its usual position over a bony prominence. There are no randomly controlled studies comparing outcomes of conservative versus surgically treated UME. The general practice is to reserve surgical treatment for patients with severe, rapidly progressive neurologic deficit or who have failed conservative treatment (Caliandro et al., 2012). Compression of the ulnar nerve at the wrist is far less common but may occur with direct compression over the wrist and hypothenar eminence. This can be caused by the use of an assistive device, such as a walker or cane, or with wheelchair propulsion.

Radial nerve involvement

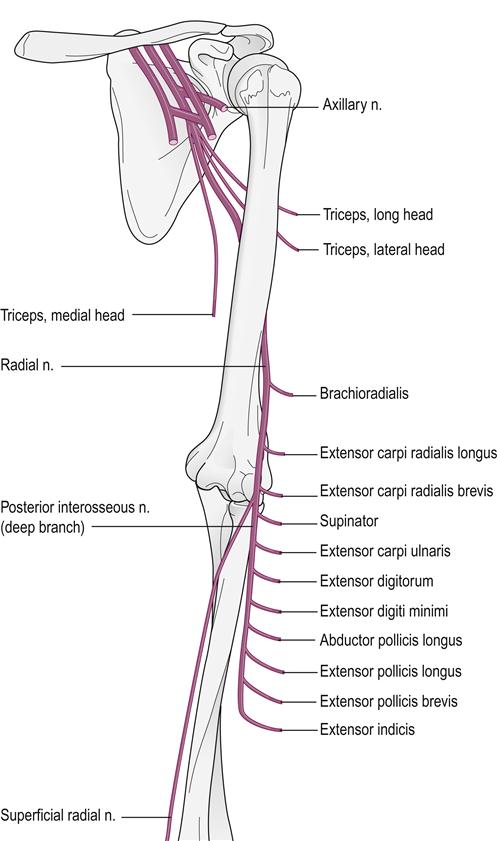

One of the pitfalls in the treatment of CTS is the development of a radial sensory neuropathy of the distal forearm. In this situation, the splint compresses the superficial radial nerve over the distal and radial aspects of the forearm. The only clinical consequence is sensory loss as there is no radial motor function in the hand-intrinsic musculature. The numbness that was initially attributed to CTS persists in the second and third digits of the hand despite the splint. At this point, however, the numbness involves the dorsum of the hand rather than the palmar aspect, but the patient may not recognize or report this subtle change. Decreased pinprick and light-touch sensation in the radial nerve distribution is noted on examination and, usually, a Tinel’s sign can be noted with gentle percussion over the superficial radial nerve in the distal forearm. The CTS signs may coexist or may have resolved. Treatment should consist of discontinuing (if the CTS is resolved) or modifying the splint to relieve the compression of the nerve.

The radial nerve can also be affected proximally. This occurs most commonly following a humeral fracture after a fall by an osteoporotic patient but it can also occur after a prolonged compression of the posterolateral humerus (Fig. 33.4). When the radial nerve is injured proximally, the hand numbness in the radial distribution is accompanied by weakness of the brachioradialis muscle and the wrist and digit extensors (Fuller, 2003). At times, the nerve is not injured acutely at the time of fracture but becomes compressed by bony callus as the fracture heals. This pattern of injury would be most evident to the patient’s rehabilitation team. Dynamic orthotics can substitute for some of the extensor functions of the digits until the return of neurological function.

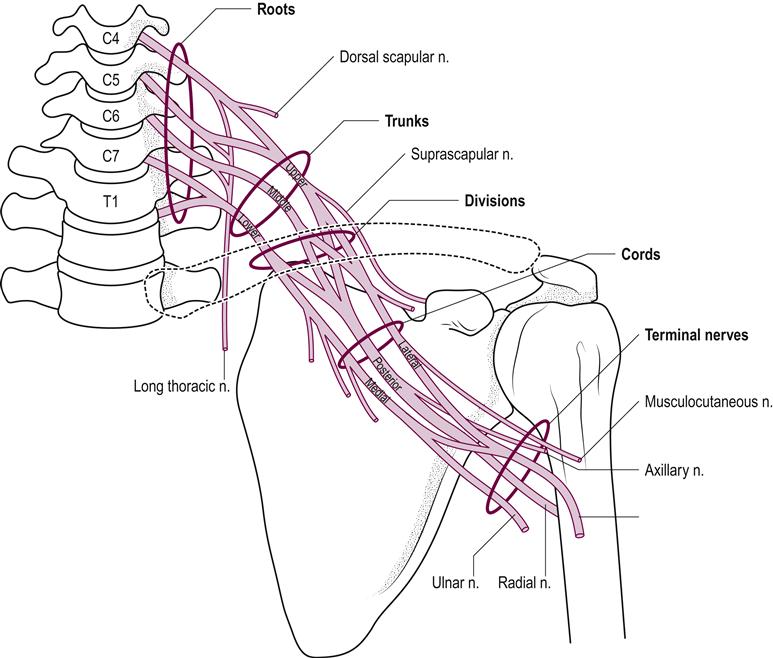

Brachial plexopathy

Another cause of hand numbness that is seen in the older population is an injury to the brachial plexus (Fig. 33.5). Common causes include trauma, tumors and remote effects from radiation, most commonly to the chest and axilla during treatment for breast or lung cancer. Motor vehicle accidents typically affect the upper trunk; the patient’s head is laterally flexed and the shoulders depressed. Such patients experience weakness in the humeral rotators and abductors and the elbow flexors, with numbness involving the lateral aspect of the arm and the first and second digits of the hand more than the fifth. Trauma after surgery usually results from the upper extremity being abducted and externally rotated, which leads to excessive stretching of the lower trunk of the plexus. This results in weakness of the hand-intrinsic musculature and numbness in the fourth and fifth digits.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree