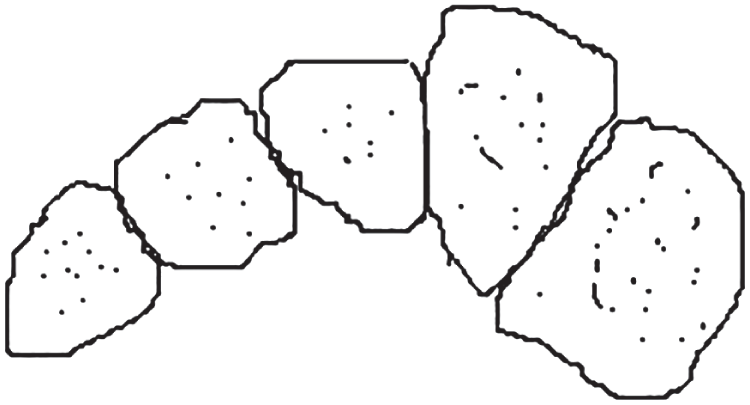

Robin R. Elliot MA FRCS, Nicholas B. Jorgensen MBBS, and Terrence S. Saxby MBBS FRACS Brisbane Foot and Ankle Centre, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia A Lisfranc joint fracture dislocation is relatively rare, 0.1–0.9% of all fractures.1 It is associated with significant morbidity and it is reported up to one‐third of these injuries are missed. In contrast, midfoot sprains are commonly seen in athletes.2 Unfortunately, a Lisfranc injury is a commonly missed diagnosis and this type of injury has the potential to lead to significant morbidity.3 Key to this is the reduction of the articulation between the second metatarsal and the middle cuneiform and fixation which replicates the function of the Lisfranc ligament, tying the medial cuneiform to the second metatarsal. Figure 107.1 The Roman arch configuration of the Lisfranc complex. Figure 107.2 Anteroposterior view showing alignment of the lateral borders of the first metatarsal and the medial cuneiform as well as the medial borders of the second metatarsal and the middle cuneiform. Lisfranc injuries require prompt anatomical reduction and surgical fixation with plates and screws. There is some debate regarding the effectiveness of primary arthrodesis as treatment for these injuries, but this has not become mainstream treatment. It is important to recognize purely ligamentous Lisfranc injuries, as these can be underappreciated, and there is emerging evidence to suggest primary arthrodesis can have a more favorable outcome in these select patients. A recent meta‐analysis (level I) concluded that there was no difference in outcomes or quality of anatomic reduction between open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and primary arthrodesis.4 Three studies were considered eligible for inclusion, and demonstrated similar patient reported outcomes, revision surgery rates, and anatomic reduction. It was demonstrated that there are greater rates of hardware removal with the ORIF group, which needs to be considered in the discussion with the patient,4 which is also supported by other studies.5 Figure 107.3 30° oblique view showing alignment of the medial borders of third metatarsal and the lateral cuneiform as well as the medial borders of the fourth metatarsal and the cuboid bone. A prospective randomized study (level I) has also demonstrated no difference,5 whereas a similarly constructed prospective, randomized study by Ly and Coetzee have shown improved short‐ and medium‐term outcomes in the arthrodesis group.6 Ly and Coetzee compared 41 patients with primarily ligamentous injuries for 42.5 months, and demonstrated an improved AOFAS midfoot score of 88 in the arthrodesis group and 68.6 in the open‐reduction group (p <0.005). The primary arthrodesis group estimated that their postoperative level of activities was 92% of their preinjury level, whereas the open‐reduction group estimated that their postoperative level was only 65% of their preoperative level (p <0.005).6 A comparative cohort study (level III) by Rammelt et al. compared 44 patients that underwent primary open reduction (22 patients) with delayed, corrective arthrodesis (22 patients) with a follow‐up of 22 months and found that the primary fixation leads to improved functional results, earlier return to work, and greater patient satisfaction than secondary corrective arthrodesis (p = 0.03).7 Figure 107.4 Weightbearing views showing instability of the left first and second tarsometatarsal joints and widening of the space between the first and second rays. Numerous level IV case series are available to demonstrate the importance of accurate reduction and internal fixation. In Myerson’s case series of 55 patients the major determinant of unacceptable results was identified as the quality of the initial reduction.8 Goossens and De Stoop’s case series of 20 patients showed that 70% of patients who were treated conservatively in an unreduced position had a poor outcome compared with only 18% of those who had reduction and pinning.9 Arntz et al. showed in a consecutive series of 40 patients that good or excellent results were obtained in 95% of patients with an anatomical reduction but only 20% of those in whom the reduction was nonanatomic.10 One case series suggested that anatomical reduction was not a guarantee of satisfactory outcome: Teng et al. reported that the subjective functional outcome in their series of 11 patients was not very good despite successful restoration of normal anatomy.11 Overall, level I evidence has shown mixed support for undertaking a primary arthrodesis for Lisfranc injury. Ly and Coetzee have demonstrated favorable outcomes for patients with a primarily ligamentous injury treated with a primary arthrodesis with a significant improvement in midfoot AOFAS scores in the arthrodesis group at two years.6 Whereas, Henning et al. demonstrated in 40 patients no significant difference in Short Form 36 (SF‐36) and short musculoskeletal functional assessment (SMFA) score.5

107

Lisfranc Injuries

Clinical scenario

Top three questions

Question 1: In a patient with a Lisfranc injury, does an anatomical reduction and fixation result in better outcomes than primary arthrodesis?

Rationale

Clinical comment

Available literature and quality of the evidence

Findings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree