Ligament Injuries in Children and Adolescents

Patrick S. Brannan MD

Henry G. Chambers MD

Ligament injuries around the knee are unusual in children and adolescents but can present significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Open physes, thick articular cartilage, and developmental issues complicate the care of the injured knee in childhood and adolescence.

Several studies have documented the increased incidence of knee injuries, particularly to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), among females who play basketball and soccer.

Children may present late with ligament or meniscal injuries because the initial examining physician underestimated the significance of the early physical examination findings.

Because of the high incidence of fractures in children, at least anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee should be obtained. A Merchant or sunrise view can be obtained to evaluate the patellofemoral joint, looking for osteochondral fractures of the patella or distal femur. A tunnel view should be obtained to evaluate the intercondylar notch and a possible osteochondral fracture.

Arthroscopy should be considered as a diagnostic alternative for children who present with knee hemarthrosis.

Although rare in children and adolescents, ligament injuries around the knee present significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The incidence and severity of the injury depends on the size of the child, their sport, and, as the adolescent approaches maturity, possibly even the sex of the child. In this chapter, the epidemiology of knee ligament injuries in children, unique physical examination findings, imaging challenges, and therapeutic approaches to the various ligament injuries are explored.

There seems to be a spectrum of injuries to the knee in children. Younger children sustain metaphyseal fractures. Teenagers with low-energy trauma may experience anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture, whereas those who have high-energy trauma may have physeal injuries (1). Fractures in the young child may be a representation of their small size and relatively lower energy imparted in sports. It has been postulated that increased ligamentous laxity (especially in children) would predispose to a greater injury rate. However, Grana and Moretz (2) found no correlation between ligamentous laxity and the occurrence or type of injury.

Alpine or downhill skiing is one of the most dangerous sports for children (3,4,5). Blitzer et al. (6) found that one fifth of skiing injuries were knee injuries. Deibert et al. (7) performed a large (>3 million skier visits), long-term (12 years) study of skiing injuries in children, adolescents, and adults. The medial collateral ligament injury rate in children from 1981 to 1987 was 20% (51 of 255 children), decreasing to 7% (19 of 273 children) for the period from 1987 to 1994. For adolescents, the rate was 9.6% (78 of 813 adolescents) in the first period and 8.8% (58 of 660 adolescents) in the second period. One ACL injury occurred between 1981 and 1987, and two occurred between 1987 and 1994. The adolescent age group had a 3.9% incidence of ACL tears in the first period and a 4.7% incidence in the second period. These findings compared with a 15.2% to 19% incidence for adults. The investigators felt that the

overall 58% decrease in children’s accidents was due to the use of properly functioning modern equipment (7). Although most of those who sustain snowboarding injuries are children and adolescents, the incidence of knee injury is significantly lower than for alpine skiing (8,9,10,11).

overall 58% decrease in children’s accidents was due to the use of properly functioning modern equipment (7). Although most of those who sustain snowboarding injuries are children and adolescents, the incidence of knee injury is significantly lower than for alpine skiing (8,9,10,11).

The quick stopping and direction in basketball and soccer predisposes the knee to ligamentous injuries. Several studies have documented the increased incidence of knee injuries among women who play basketball (12,13) and soccer (14,15). Gray et al. (16) reported a total of 19 ACL ruptures in female players compared with only four ACL injuries in male basketball players during the same period. Possible causative factors for this increase in ACL injuries in women may be extrinsic (i.e., body movement, muscular strength, shoe–surface interface, and skill level) or intrinsic (i.e., joint laxity, limb alignment, notch dimensions, and ligament size) (17,18). Additionally, others have suggested that differences in dynamic movement patterns and proximal muscle firing patterns play a role in the increased propensity for females to tear their ACL (19). Loudon et al. (20) found a significant correlation between ACL injuries and knee recurvatum, “navicular drop,” and extrinsic subtalar pronation.

Football represents the leading cause of ACL tears in adolescents (21,22,23,24). In a survey of coaches from Kentucky, Stocker et al. (25) found an incidence of 0.055 knee injuries per player (257 knee injuries in 4,690 players). Volleyball also had a significant rate of ACL and medial collateral ligament injuries, with the most injuries caused from landing from a jump in the attack zone (26). Other sports commonly associated with ACL injuries include soccer (rate of 3.7 to 5.6 injuries per 1,000 hours and one ACL tear) (27) and wakeboarding (28).

A high index of suspicion must be entertained when evaluating children or adolescents with knee injuries. Many children present late with ligamentous or meniscal injuries because the initial examining physician underestimated the significance of the physical examination findings and a hemarthrosis. Luhmann (29) found that ACL injuries, meniscal tears, and patellofemoral pathology accounted for 87% (48 of 55) of diagnoses of hemarthrosis in children 18 and younger. ACL pathology was much more common in males (13 of 16 diagnoses), whereas patellofemoral pathology was much more common in females (11 of 14 diagnoses). Overall, the differential diagnosis for a child with an acute hemarthrosis includes ACL tears, tibial spine avulsion fractures, patellar dislocations, osteochondral fractures, meniscal tears, physeal fractures of the distal femur, and medial collateral ligament tears (30). A posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tear may not demonstrate a large hemarthrosis.

Associated injuries are not uncommonly found in children with ligamentous pathology. Twenty-six of 31 patients with ACL tears were found to have associated injuries including meniscal tears, medial collateral ligament ruptures, and even femur fractures. Furthermore, there is a higher incidence of medial meniscal tears in children with chronic ACL tears (36%) (31).

ACL Injury

The standard physical examination techniques (e.g., Lachman, anterior drawer, pivot shift) used in evaluating adults have the same validity in children (32,33,34). Although children do have greater ligamentous laxity than adults, a side-to-side comparison usually aids in the diagnosis. Children are often more apprehensive than adults, and it can be difficult to perform these tests, particularly the pivot shift test. Physical examination of the child under general anesthesia increases its accuracy. Donaldson et al. (35) found that the pivot shift test was initially positive in only 35% of knees, increasing to 98% under general anesthesia. The Lachman test was equally sensitive to examination under anesthesia. The anterior drawer test was positive in 70% of knees, increasing to 91% under general anesthesia. Instrumented analysis (e.g., KT-1000 Ligament Arthrometer; Med-Metric, San Diego, CA) has a great advantage in the documentation and reproducibility of side-to-side differences. Newer testing equipment designed for children has been introduced and may further aid in the evaluation of children with ACL injuries.

Tibial Spine Avulsion Injuries

Tibial spine avulsion injuries manifest with a large hemarthrosis and with signs of an ACL injury (e.g., positive Lachman test, positive anterior drawer test). The meniscus (usually medial) may be entrapped in the fracture site. Mah et al. (36) found that, in nine of 10 displaced tibial spine fractures, there was interposition of the meniscus. The diagnosis is usually made by the anteroposterior and lateral radiograph results. Radiographs should be obtained as part of the examination of any knee in a child or adolescent with a hemarthrosis. A severe medial ligamentous injury also may be associated with a tibial spine fracture (37).

Patellar Dislocation

Often, the medical history of children is difficult to elicit. Even with ACL injuries, they say that their “knees dislocated.” Patellar dislocations are frequently associated with a large hemarthrosis. Tenderness is experienced in the medial peripatellar region, and there is an occasional defect in the retinaculum. There may also be tenderness at the adductor tubercle, including a patellofemoral ligament tear.

Osteochondral Fractures

A twisting knee injury or a patellar dislocation can lead to a chondral or osteochondral fracture. A tense hemarthrosis with

tenderness over either femoral condyle of a flexed knee may signify an osteochondral fracture. Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to help define the lesion and its extent. Chondral lesions are more common in children because the cartilage is thicker and therefore more prone to shear injury. Frequently, the diagnosis is made only at the time of arthroscopy.

tenderness over either femoral condyle of a flexed knee may signify an osteochondral fracture. Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to help define the lesion and its extent. Chondral lesions are more common in children because the cartilage is thicker and therefore more prone to shear injury. Frequently, the diagnosis is made only at the time of arthroscopy.

Physeal Fractures

Physeal fractures are rare injuries of the distal femur. They must be distinguished from medial collateral ligament or lateral complex injuries in the child. There is usually a tense hemarthrosis with tenderness along the entire distal femur at the physis (i.e., adjacent to the upper pole of the patella or 2 to 3 cm above the joint line). If the fracture is limited to one condyle, tenderness will be greater at the involved physis. Laxity may be identified on varus or valgus stress testing. A diagnosis is usually made on the basis of plain radiographs. Occasionally, stress radiographs may be necessary to distinguish collateral ligament injury from physeal fractures. This is especially true in children and adolescents who have severe soft issue edema and ecchymosis.

Meniscal Tears

Meniscal tears are often associated with ACL tears, medial collateral ligament tears, or both and can lead to a significant hemarthrosis. Popping and especially locking of the knee in slight flexion are important symptoms. Joint line tenderness is very helpful if present, but its absence does not exclude a diagnosis of a meniscal tear. The McMurray test is nonspecific, but a positive result may suggest further investigation. In the very young child, clunking and increased laxity on the Lachman test may indicate a discoid meniscus.

Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries

Tenderness of the medial knee at the origin, midsubstance, or insertion of the medial collateral ligament aids in the diagnosis of a ligament strain (grade 1). With valgus stress applied to the knee in slight flexion, there may be opening of the joint with a good end point (grade 2). If the knee opens medially without an end point, there is a grade 3 tear with the possibility of a concomitant ACL tear. The children rarely have a large effusion, which differentiates this injury from a distal femoral physeal injury.

Tibial Tubercle Avulsion Injury

A large hemarthrosis occurs when there is an avulsion of the tibial tubercle with the patellar tendon. There is tenderness and edema over the entire surface of the knee, and crepitus may be present over the tibial tubercle. The patella is often high riding. This injury may be missed on a cursory examination because the finding of patella alta on the lateral radiograph is often subtle. In more extensive fractures, the fracture line may extend posteriorly into the knee joint and include the ACL (Fig 56-2).

PCL and Posterolateral Complex Injuries

PCL tears are rare in children (39). The physical findings are the same as for adults. However, because of their rarity, the injury is often missed at first examination. It is usually diagnosed when the child or adolescent begins complaining of pain in the knee and medial joint line symptoms. Children have a higher incidence of bony avulsion fractures from the posterior tibia than adults. These fractures are amenable to open reduction and internal fixation.

Although the history and clinical examination suggest the diagnosis in most cases, imaging studies are often needed. Because of the high incidence of fractures in this age group, at least anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee should be obtained. It is also recommended that a Merchant or sunrise view be obtained to evaluate the patellofemoral joint, looking for osteochondral fractures from the patella or distal femur. A tunnel view should be obtained to evaluate the intercondylar notch and a possible osteochondral fracture. Occasionally, oblique radiographs of the knee are necessary to identify avulsion fractures at the medial and lateral margins of the proximal tibia.

MRI can be used to confirm the clinical diagnosis or to make the diagnosis if the clinical diagnosis is in question. Gelb et al. (40), however, found (in adult patients) that MRI was only 95% sensitive and 88% specific for the diagnosis of ACL tears relative to a 100% specificity and sensitivity for clinical examination. The results were even poorer for meniscal injuries (82% and 87%) and worse in articular surface damage (33%). They concluded that MRI is unnecessary in most knee disorders and not a cost-effective test (40,41,42). MRI does not appear to be helpful in the grading of medial collateral ligament tears (43). In studies in which MRI was used to evaluate knee injuries in children, investigations found that, although the MRI might aid in the diagnosis of the meniscal injuries, there was still a problem identifying the ACL because of its small size (44,45) or because of the poor sensitivity of MRI in finding an ACL tear (64%) (46). More recent studies have found MRI to be a helpful adjunct in the evaluation of knee injuries. Major et al. (47) found MRI to be 100% sensitive and specific for

ACL injuries and 93% sensitive and 95% specific for lateral meniscal injuries. Lee et al. (48) found a 95% sensitivity rate and 88% specificity rate for ACL injuries. Rangger et al. (49) suggested that MRI should be done in all cases in which the clinical diagnosis has been reduced to a suspected meniscal injury. MRI has also been effective in the diagnosis of posterolateral complex injuries of the knee (50) and is the only way to diagnose bone bruises or contusions (51,52).

ACL injuries and 93% sensitive and 95% specific for lateral meniscal injuries. Lee et al. (48) found a 95% sensitivity rate and 88% specificity rate for ACL injuries. Rangger et al. (49) suggested that MRI should be done in all cases in which the clinical diagnosis has been reduced to a suspected meniscal injury. MRI has also been effective in the diagnosis of posterolateral complex injuries of the knee (50) and is the only way to diagnose bone bruises or contusions (51,52).

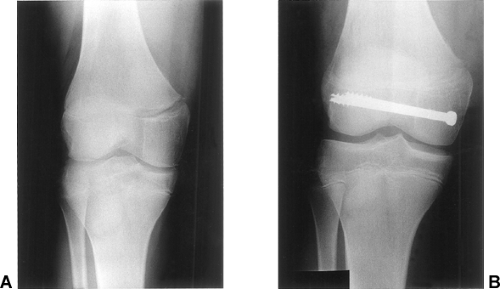

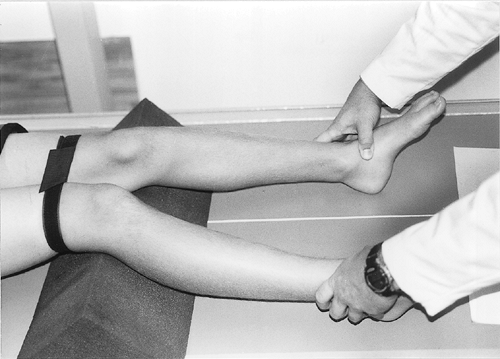

The diagnosis of collateral ligament injuries can be very difficult. There is an inherent laxity in many children, and differentiation between ligamentous and physeal injuries is critical. The use of stress radiographs can be helpful. The best method of performing a radiographic stress test, especially if trying to distinguish between a medial collateral ligament injury and a Salter Harris I fracture of the distal femur, is to place the child supine and tie a belt or strap around the distal thighs with the knees slightly flexed (approximately 20 degrees) over a pillow. The feet are then abducted as the radiograph is taken (Fig 56-3). The simple test differentiates medial collateral ligament tears, which open at the joint, from a Salter Harris I fracture, which opens at the physis. As previously stated, patients who have a physeal fracture often have a large hemarthrosis, which is not usually present in collateral ligament injuries. Other than its use in differentiating physeal fractures from medial collateral ligament tears, stress radiography seems to have little role in the evaluation of knee injuries in children. Although stress radiography is sensitive in the diagnosis of PCL tears, clinical examination or MRI provides sufficient information (53,54).

My approach to the use of imaging in children’s knee injuries is to obtain anteroposterior, lateral, tunnel, and Merchant views of all injured knees. Comparison views may be necessary but are not ordered routinely. Knee pain in children may be referred from hip pathology such as Legg-Calve-Perthes syndrome or slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and if there is any doubt, anteroposterior and frog lateral pelvis radiographs should be obtained. Occasionally, the child is uncooperative or too uncomfortable to examine. An examination can be performed 7 to 10 days later. If there is still a question of a ligamentous laxity injury or meniscal tear, an MRI scan can be ordered, with the realization that it may not be the definitive test. Rarely, when it is difficult to distinguish between physeal fractures and a medial collateral ligament tear, stress radiographs can be performed.

After a complete clinical examination and appropriate injury studies, the diagnosis may still be in doubt. Several studies have addressed this problem in children with hemarthroses. Ure et al. (55) performed arthroscopy in 104 patients younger than 18 years old who had hemarthroses. They found that the most frequent diagnosis was patellar dislocation (45% of children and 29% of adolescents). The preoperative diagnosis was shown to be wrong or incomplete in 41% of the children and 24% of the adolescents, and in only 36% of the children were meniscal tears suspected before surgery. They concluded that every child with a hemarthrosis should have an arthroscopy. Faraj et al. (56) reported that clinical diagnosis and arthroscopic findings were compatible and correct in 61% of preadolescent patients. Matelic et al. (57) reported similar findings for 21 children, with osteochondral fractures found in 14 (67%) of the patients. The highest incidence of unsuspected pathologic findings from clinical examination and standard imaging, coupled with findings of additional pathology (i.e., meniscal tears, osteochondral and chondral fractures, and partial ACL tears), warrants considering diagnostic arthroscopy in all children who have an acute hemarthrosis (58,59,60,61,62,63,64).

Collateral Ligament Injuries

Medial collateral ligament injuries often occur in conjunction with other ligamentous injuries (e.g., ACL), osteochondral fractures, or meniscal injuries (65). It was once thought that medial collateral ligament injuries could not occur before physeal closure. However, it is clear that medial collateral ligament tears do occur at the origin, midsubstance, or insertion of the ligament (66).

Earlier studies suggested that the injured medial collateral ligament needed to be repaired or at least immobilized, especially in the presence of an ACL tear (67,68). However, later studies suggest that treatment with a cast brace or prefabricated brace with free range of motion can lead to good or excellent results (69,70,71,72). Isolated tears of the medial collateral ligament should be treated by placing the knee in a range-of-motion brace set from 0 degrees to 90 degrees. After 10 to 14 days, the range of motion can be increased to full flexion. The brace is left in place for 4 to 6 weeks. The knee should be tested for laxity before allowing the child or adolescent to return to cutting activities.

Lateral collateral injuries may have associated bony avulsions or even fibular physeal injuries. These physeal injuries are usually nondisplaced or minimally displaced but should be treated with immobilization in a knee immobilizer or cylinder cast. An ACL tear may be associated with a lateral collateral ligament tear. Associated posterolateral complex injuries must be completely excluded because they often require operative repair, even in children and adolescents.

PCL Injury

PCL injuries are rare injuries in children and are therefore often missed at the initial evaluation of a knee injury (73). It can be helpful to know the mechanism of injury, which is usually a fall on a flexed knee, a dashboard injury in a motor vehicle accident, or severe hyperextension (74,75). A PCL injury has been found in a 10-year-old child after a femur fracture (76). The degree of joint effusion is usually less than with an ACL tear, and evaluation of posterior laxity can be difficult in a child (77). PCL injuries may be associated with disability from degenerative disease of the medial joint compartment (78,79). There is no association between objective laxity and subjective knee scores or ability to return to sport (80).

Children have a higher incidence of bony avulsion injuries from the tibial insertion but may also have a bony avulsion from the femur. Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the knee usually demonstrate the avulsion (81). Midsubstance tears can be identified with MRI (Fig 56-4).

The bony avulsion should be repaired with interepiphyseal sutures or screw fixation (82). Arthroscopies should be performed before prone positioning of the patient because of the high incidence of associated injuries (83). Because the repair of PCL injuries is controversial in adults, it may be prudent to treat the knee with physical therapy (range of motion) and strengthening combined with a PCL brace (keeping the knee in slight flexion) until the child is skeletally mature (84,85,86,87,88).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree