Lateral Epicondylitis

Robert P. Nirschl

Bernard F. Morrey

INTRODUCTION

Currently, we prefer the term tendinosis to epicondylitis as this is more descriptive of the true pathology (1). Epicondylitis (tendinosis) occurs at least five times more commonly on the lateral than on the medial aspect of the joint. The selection factors to determine the candidates for surgery are similar for each process, yet there are some distinct features with regard to the surgical technique (2). Thus, medial epicondylitis is discussed separately in Chapter 25.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications

Pain is the major indication for surgery of lateral epicondylitis. There are three broad indications and a fourth feature to consider.

Pain is of significant intensity as to limit function and interferes with daily activity or occupation (Nirschl Pain Phases 5, 6, or 7) (3) (Table 24-1).

Localization is precisely at the attachment area of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) or the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) at and just distal to the lateral epicondyle.

A legitimate period of nonoperative management has been attempted; this typically includes at least 6 months of activity modification, counterforce forearm band, anti-inflammatory agents, and a quality rehabilitation program (4).

Failure of cortisone injections is no longer considered an absolute necessity prior to offering surgical intervention. However, if injections have been used and the patient is no longer benefiting or has not benefited from them, then the patient is a candidate for a surgical procedure. The technique of injection (e.g., properly placed under the ECRB tendon) is important regarding these considerations (5).

Contraindications

The contraindications to surgical intervention include an inadequate nonoperative program (4) and patients who have demonstrated lack of compliance with the recommendations, particularly that of activity modification. Individuals on workers’ compensation disability should be assessed on several occasions to assure that the above indications have been met.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Physical findings include local tenderness to palpation over the tendon origin at the epicondyle. Provocative tests of pain with resisted wrist extension for lateral involvement are invariably positive especially with the elbow in full extension. In some cases, the symptoms may be aggravated by performing the test with the elbow in 90-degree flexion (a sign indicating substantial tendinosis) (4,6). If forearm pain is a component (unusual), examine for posterior interosseous nerve irritation (an independent malady) (7). The most sensitive test is pain on resistive supination (8).

The most commonly involved tissue, the pathologic process, and the principles of the surgical intervention should be reviewed prior to undertaking the surgical procedure (9).

TABLE 24-1 Tendinosis Phases of Pain | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The hallmarks of good surgical concept and technique include precise identification of the pathologic tissue, resection of all involved pathology, maintenance of normal tissue attachments, protection of normal tissue, enhancement of vascular supply, firm repair of the operative site, and quality postoperative rehabilitation.

Kraushaar and Nirschl (1) have now defined the histopathology in precise detail utilizing the methods of electron microscopy and a histoimmunochemistry. The ECRB (100%) and the extensor communis (anterior edge) are the tissues most commonly involved laterally (100% and approximately 35%, respectively) (10,11,12 and 13). Histologically, the pathologic tissue is devoid of inflammatory cells but has a characteristic pattern of immature fibroblasts and vascular elements (1,14). Recent electron microscopic evidence reveals lack of extracellular cross-linkage (1). Current recommended technique specifically focuses on demonstrated pathoanatomy. It should be noted that although the classical case, in our experience, is angiofibroblastic tendinosis in the ECRB, the anteromedial edge of the EDC origin has concomitant pathology in 35% of cases and, when present, should be addressed. Additional pathologies include bony exostosis of the lateral epicondyle in 20% of cases and anterolateral compartment intra-articular pathology such as synovitis, plica, and chondromalacia (5%) (9).

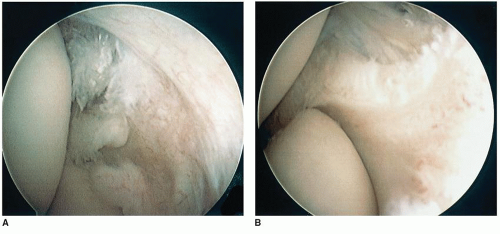

Intra-articular changes as noted above have also been observed with the advent of elbow arthroscopy as a therapeutic tool (Fig. 24-1). Today, we specifically assess by clinical exam and imaging studies the possibility of any symptom-producing intra-articular element (5% in our experience) and proceed accordingly with possible arthroscopy or limited arthrotomy in such cases (3,15,16).

SURGERY (LATERAL EPICONDYLITIS)

The described technique and illustrations apply for the large majority of cases. It should be noted, however, that individual variations can and do occur. In these instances, the pathologic variations should be addressed as presented.

FIGURE 24-1 Arthroscopic identification of intra-articular pathology (A); resection of synovitis (B). |

Arthroscopy

The data on arthroscopic debridement are incomplete at this time to draw a conclusion or to recommend this treatment with the exception of clearly identified symptom-producing intra-articular issues (15). Overall, for the typical extra-articular case, there is no advantage over the mini-open technique (16). Disadvantages of arthroscopy include increased risk to nerves and joint surfaces plus increased cost (e.g., extra O.R. time plus instrument cost). More importantly, the excision of pain-producing tendinosis tissue may be incomplete

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree