CHAPTER 10 Lateral Approach to Hip Arthroscopy

Introduction

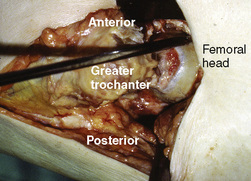

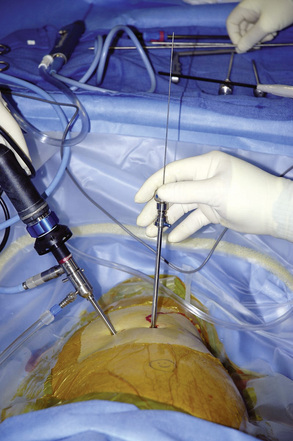

Hip arthroscopy was first performed in our practice with the use of the supine approach on a fracture table for distraction. During our early experiences, problems of getting into the hip joint and complications such as the scuffing of articular cartilage, poor maneuverability, and the inability to achieve the result before extensive extravasation made the procedure difficult. Specific instruments were not developed, and distraction parameters were not established. As a result, the procedure was not predictable for entering the intra-articular space that is now known as the central compartment. In 1931, Burman was the first to use an arthroscope in the hip in a cadaveric study. However, he was unable to enter the central compartment, even with distraction. Our associate James M. Glick, MD, performed 11 procedures between 1977 and 1982, and he had difficulty getting in on two occasions. Because of our experience with the lateral decubitus positioning in total hip replacements, the idea of approaching hip arthroscopy in a similar way was developed. We dissected a cadaver hip to determine the most direct access to the intra-articular space, and we then described the anterior–peritrochanteric and posterior–peritrochanteric trochanteric portals (Figure 10-1); these have subsequently been referred to as the anterolateral and posterolateral portals. In 1986, distraction was introduced by Erikkson with the use of a fracture table to facilitate entry into the central compartment. We developed a rope-and-pulley system with weights as we used for shoulder arthroscopy as our first hip distractor (Figure 10-2). The first patient in whom we performed arthroscopy with the lateral approach was a massively obese woman with hip pain in whom Dr. Glick had previously performed arthroscopy without success in the supine position. In the lateral decubitus position, the obese portions of her thigh drooped down to expose a prominent greater trochanter. The neurovascular structures are safely away from the portals, and the surgeon is very familiar with their location; these portals offer a direct shot into the femoroacetabular joint. Many of the surgeons interested in hip arthroscopy at that time adopted the technique and continue to use it today.

The major advancements in getting into the central compartment were a result of distraction and the use of Nitinol wire cannulated trochars (Figure 10-3). Later, the development of longer arthroscopes, slotted (half-pipe) cannulas, and curved and flexible instruments allowed for advanced techniques that have followed a similar path as those used for knee and shoulder arthroscopy.

Indications

Surgical technique

Patient Positioning

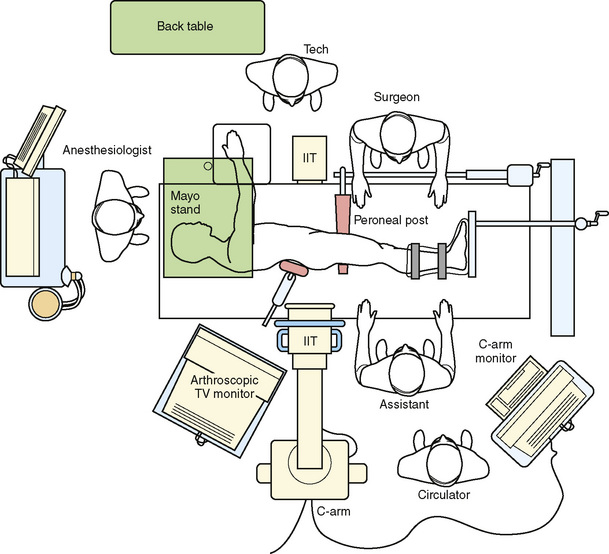

The patient is placed on a well-padded operating room table in the lateral decubitus position (Figure 10-4). An axillary roll is positioned, and hip positioners are used to support the pelvis. By preventing the pelvis from rolling back on the perineal post, the risk of pudendal neuropraxias may be reduced.

We typically drape with split sheets, and we use a large plastic pouch to catch fluids.

Distraction

For optimal viewing and safe surgery, at least 1.2 cm of distraction is required before the femoroacetabular joint (central compartment) is entered. Three commercially available distractors for the lateral approach are available from Mizuho OSI (Union City, CA 94587-1234), Innomed, Inc. (Savannah, GA, 31404), and Smith & Nephew. The Mizuho OSI and the Smith & Nephew distractors have the advantage in that hip mobility is adjustable during surgery (Figure 10-5).

The perineal post should have padding of at least 9 cm in diameter, and it should be positioned eccentrically over the pubic symphysis, with little to no compression to the downside thigh (Figure 10-6).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree