Laryngeal Disorders

Richard J. H. Smith

Benjamin B. Cable

LARYNGOMALACIA

Stridor is a high-pitched, musical sound that is produced by airflow turbulence resulting from partial obstruction of the airway. It must be differentiated from other airway sounds, such as stertor, wheezes, rhonchi, and rales. Although the etiology of stridor is multifactorial, often the location of the airway obstruction can be determined by careful listening. For example, inspiratory high-pitched stridor with a relatively normal voice usually denotes supraglottic obstruction; biphasic (inspiratory and expiratory) stridor of intermediate pitch is heard with glottic or subglottic obstruction; and expiratory stridor associated with a “barking” cough indicates intrathoracic tracheal obstruction.

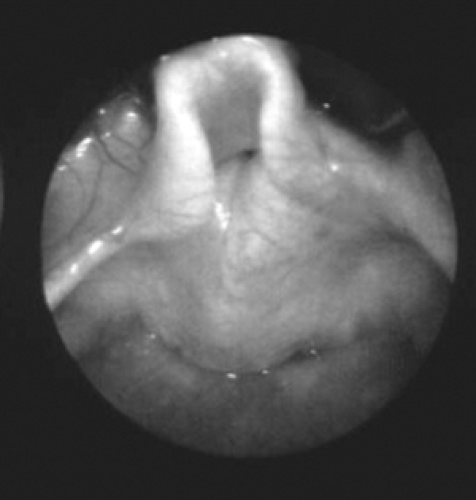

Congenital laryngeal stridor or laryngomalacia is the most common form of stridor in infants and accounts for approximately 80% of all cases of pediatric stridor. It is characterized by an inspiratory, harsh, high-pitched stridor that arises from medial prolapse of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, or arytenoid cartilages (Fig. 234.6). Usually, the tissues obstructing the laryngeal inlet are the aryepiglottic folds and the arytenoids (67% of cases), although combined posterior and anterior obstruction caused by the arytenoids and epiglottis, respectively, is not an infrequent finding (30% of cases). However isolated, anterior (epiglottic) obstruction is rare (fewer than 3%). The pathophysiology of laryngomalacia includes poor neurologic control or hypotonia, redundant laryngeal soft tissue, and inadequate cartilaginous support (hence the name laryngomalacia or soft larynx). The differential diagnosis includes subglottic stenosis, vocal cord paralysis, and tracheomalacia, a relatively rare disorder presenting either as idiopathic tracheomalacia or as secondary to extrinsic compression, often from a vascular malformation.

Nearly always, laryngomalacia is noticed within the first few weeks or months of life, and an initial diagnosis of laryngomalacia made after the age of 2 years should be questioned. The stridor is intermittent and mild and occasionally becomes exacerbated by crying, supine positioning, and upper respiratory infections. Cyanosis, hoarseness, feeding difficulties, atypical stridor, failure to thrive, and apneic spells indicate the need for a complete diagnostic evaluation and possible operative intervention. However, most cases resolve spontaneously by the time this child reaches age 12 to 18 months.

The diagnosis of laryngomalacia can be made with a high degree of certainty on the basis of an office examination complemented by flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Although some investigators recommend that all children with laryngomalacia undergo direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, or flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy, to rule out concomitant airway disease, a review by Mancuso and colleagues reported a significant second airway lesion in only 4% of 233 children with laryngomalacia. More importantly, the nine children with other airway lesions had atypical histories and unusual stridor. Although prudence would prompt evaluation of the entire airway in infants with laryngomalacia, unless the pattern of

obstruction of the airway suggests that the laryngomalacia is unusually severe or otherwise atypical, routine direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy or flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy are not cost effective.

obstruction of the airway suggests that the laryngomalacia is unusually severe or otherwise atypical, routine direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy or flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy are not cost effective.

FIGURE 234.6. Laryngomalacia affecting the posterior airway with collapse of the aryepiglottic folds and arytenoid tissue during inspiration. |

BOX 234.1. Anatomic Considerations in Laryngeal Disorders

A neonatal larynx differs from an adult larynx not only in size but also in relative dimensions and location. A neonate’s larynx is approximately one-third the size of its adult counterpart. The average cross-sectional area of an infant’s glottis is approximately 15 mm2, which is relatively small when compared with an adult glottis. The epiglottis is proportionately larger (1.38:1.00), and this relative difference in size and the position of the larynx high in the neck are instrumental in allowing infants to suckle and breathe simultaneously. During swallowing, the epiglottis abuts the soft palate to create lateral digestive channels that funnel food into the piriform fossae and esophagus while the midline airway remains patent and effectively separated. Olfaction also may be enhanced by the neonate’s ability to breathe while swallowing.

Descent of the larynx to a lower position in the neck begins at age 2 years. During infancy, the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage is located at the fourth cervical vertebra, but by puberty, its location is at the level of the seventh cervical vertebra. This change in position creates a confluence of the digestive and respiratory tracts and results in a longer vocal tract, which is ideal for complex speech and articulation. However, this lengthening abolishes the ability to suckle and breathe simultaneously. Growth of the larynx continues until puberty, by which time full laryngeal development has occurred.

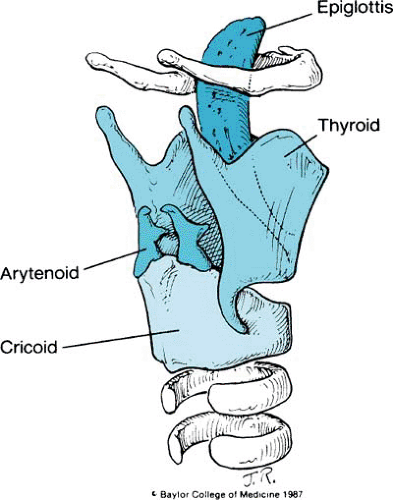

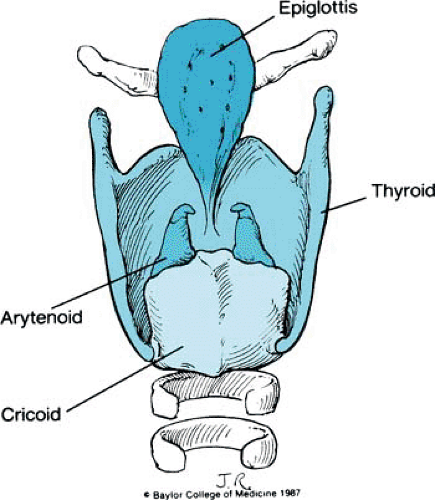

The membranoskeletal framework of the larynx is composed of several cartilages to which are attached muscles and folds of tissue that render respiration, phonation, and deglutition possible. The intricacies and subtleties of these structures are complicated, but their basic anatomy is relatively simple. The major cartilages of the larynx are the cricoid, thyroid, epiglottis, and arytenoids.

Only the cricoid, with a broad arch posteriorly and a narrow arch anteriorly, forms a complete ring. Attached superiorly is the sharply flexed, shieldlike thyroid cartilage; its more important features include paired superior and inferior horns, lateral plates or laminae, and the thyroid notch. In lateral profile, the notch forms an anteriorly projecting angle known as the laryngeal prominence or Adam’s apple. Facets on the inferior horns articulate with the posterior arch of the cricoid, establishing a hinge motion between the two cartilages (Fig. 1).

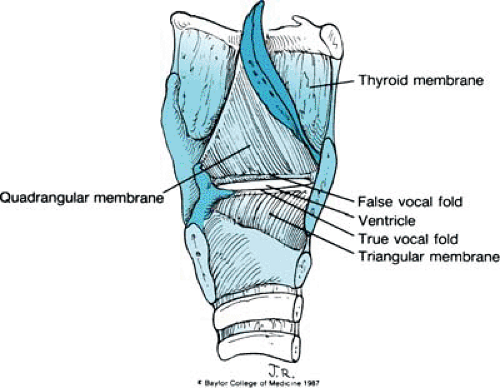

The leaflike epiglottis is tucked within the thyroid cartilage. It is made of fibroelastic cartilage and is attached inferiorly to the thyroid cartilage just above the level of the true vocal cords. From its midportion, the epiglottis is attached to the tongue by the median and lateral glossoepiglottic folds. From both lateral borders of the epiglottis, quadrangular membranes arise and arch posteriorly to the arytenoids. So named because of their shape, the quadrangular membranes are as tall as the epiglottis anteriorly and are only as high as the ipsilateral arytenoid posteriorly. Both the superior and the inferior borders of each quadrangular membrane are free (Figs. 2 and 3).

The arytenoid cartilages are paired paramedian structures. Each has an apex, a concave base that rests on the underlying cricoid cartilage, a lateral process to which attach many of the intrinsic muscles of the larynx, and an anteriorly projecting vocal process. A second laryngeal membrane—the triangular membrane or conus elasticus—originates from this anteriorly projecting vocal process and continues anteriorly to the thyroid cartilage. Its superior edge is thickened and forms the vocal ligament. Inferiorly, the triangular membrane attaches to the cricoid cartilage (see Fig. 3). Two minor paired cartilages also are present. The corniculate cartilage lies on the superior portion of the arytenoids and contributes to the height of the posterior glottis. The small and sometimes rudimentary cuneiform cartilages are located in the aryepiglottic folds and may act like a batten to stiffen the folds.

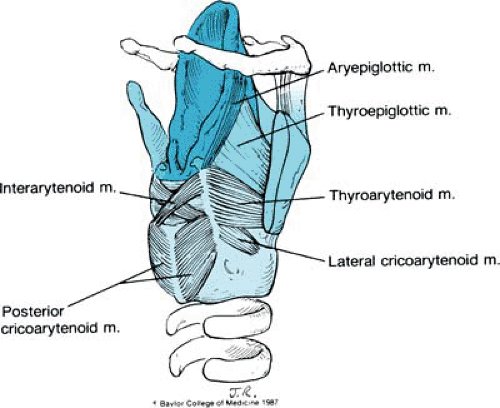

Overlying these structures are the laryngeal muscles and mucosa. To aid in our understanding of the anatomic associations, we divide the intrinsic muscles of the larynx into two groups. One group, comprising the thyroarytenoid, the thyroepiglottic, and the aryepiglottic muscles, is associated with the quadrangular membrane. The second group, comprising the posterior cricoarytenoid, the lateral cricoarytenoid, and the interarytenoid muscles, acts on the arytenoid cartilages.

A seventh muscle, the vocalis muscle, parallels the vocal fold and is part of the thyroarytenoid muscle (Fig. 4).

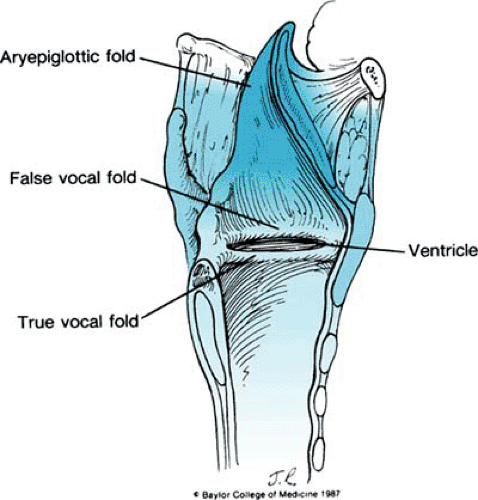

FIGURE 234.5. Overlying mucosa that creates three important folds: the aryepiglottic folds, the false vocal cords, and the true vocal cords. |

The overlying mucosa forms three important folds: the aryepiglottic folds, the false vocal cords (representing the inferior borders of both quadrangular membranes), and the true vocal folds. With the exception of the true vocal folds, which are covered by stratified squamous epithelium, the mucosa from the trachea to the aryepiglottic folds is pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (Fig. 5).

The major functions of the larynx—respiration, phonation, and deglutition—require certain positions of the vocal cords for optimal operation. On maximal respiration, the vocal cords become flattened. During phonation, they are lightly juxtaposed. During swallowing, maximal closure of the airway occurs by the coordinated apposition of the vocal cords, the sphincteric action of the aryepiglottic folds, and elevation of the larynx to the tongue base.

Trauma or pathologic changes involving the larynx may affect the dynamics of the vocal cord. If function becomes compromised, such symptoms as stridor, hoarseness, and aspiration can develop. They are the harbingers of potentially serious laryngeal problems and dictate that an adequate laryngeal evaluation be performed. Examination may require simple flexible fiberoptic visualization or a more detailed study using rigid laryngoscopes and bronchoscopes with the patient under general anesthesia.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) also may play a role in stridor and laryngomalacia. Little and associates reported on the high incidence of GERD in children with laryngeal anomalies, in particular laryngomalacia, as compared with children without laryngeal disorders. Possible explanations for this association include GERD-induced triggering of neurologic laryngeal reflex pathways, GERD-induced mucosal edema, or secondary aspiration. These data suggest that in children with severe laryngomalacia, evaluation of GERD with video swallow studies or a 24-hour pH probe should be considered.

Treatment of laryngomalacia usually is unnecessary, and reassurance to parents is all that is required. Approximately 90% of children will experience a slow resolution of their stridor over the course of time without intervention. Indications for intervention in the remaining 10% of the population with laryngomalacia include significant respiratory compromise and failure to thrive. Respiratory compromise is considered when children demonstrate severe stridor as well as retractions with evidence of desaturations by oximetry. Failure to thrive sometimes can result from the significant increase in the overall work of breathing these children require. All children with laryngomalacia should be monitored closely for appropriate weight gain, and those failing to obtain target gains should be returned to their consulting otolaryngologist for treatment.

Surgical therapy for laryngomalacia can be directed at removing the redundant supraglottic tissue (endoscopic, often laser-assisted, ablation of excess supraglottic tissue, a so-called supraglottoplasty) or bypassing the larynx (tracheotomy). The former intervention has come to the forefront and is 70% to 90% effective in resolving airway obstruction and obviating a tracheotomy. Postoperative complications are minimal, and no long-term morbidity has been reported. Tracheotomy is the treatment of choice for supraglottoplasty failures as well as for those children with concomitant disorders such as cardiovascular anomalies, pulmonary disease, or other airway lesions that require airway stabilization.

LARYNGEAL STENOSIS

Laryngeal stenosis is a term used to describe the presence of airway compromise involving the glottic or subglottic larynx. Although it is rare, supraglottic laryngeal stenosis also can occur. In most instances, glottic and subglottic stenoses result from prolonged intubation; however, some children who never have been intubated have subglottic stenosis secondary to a congenitally small airway. Congenital subglottic stenosis can be diagnosed with certainty only before any attempt at intubation. Although no one knows the proportion of intubated neonates who have laryngeal stenosis because of a preexisting subglottic stenosis, the size of the subglottis does vary. In approximately 1% of children, the larynx is one endotracheal tube size (1 mm) smaller than predicted; in 0.06%, the larynx is three tube sizes (1.5 mm) too small. Doubtless, some intubated infants have a smaller-than-normal larynx and therefore a greater risk for sustaining damage from an endotracheal tube. Although endoscopy is required to assess the larynx properly and to determine its size, preintubation laryngoscopy is not practiced; instead, the intubating physician must use gentle pressure to size the larynx with the selected endotracheal tube. If the fit seems tight, a smaller tube should be used. Ideally, the endotracheal tube should allow an audible leak at or below a pressure of 20 cm H2O. Cuffed endotracheal tubes can obscure measurements of leak pressure and rarely are required in small children. Congenital stenosis at the subglottic level usually is secondary to a cartilaginous abnormality. Typically, the cricoid circumference is smaller than normal and somewhat flattened (Box 234.2). Another common finding is telescoping of the first

tracheal ring within the cricoid cartilage and, as a consequence, narrowing of the airway. In addition, compromise of the soft tissue airway occurs if increased amounts of connective tissue or numerous hyperplastic-dilated mucous glands encroach on the subglottic lumen.

tracheal ring within the cricoid cartilage and, as a consequence, narrowing of the airway. In addition, compromise of the soft tissue airway occurs if increased amounts of connective tissue or numerous hyperplastic-dilated mucous glands encroach on the subglottic lumen.

BOX 234.2. Differential Diagnosis of Glottic and Subglottic Stenosis

Glottic stenosis

Anterior or posterior web or scar

Vocal fold fixation

Tumor (papillomas, hemangiomas)

Saccular cysts

Bilateral vocal cord paresis

Postintubation granulation tissue

Subglottic stenosis

Firm stenosis (cartilaginous)

Cricoid cartilage

Normal configuration, small size

Deformed cartilage

Flattened anterior or posterior lamina

Cleft (submucous, partial, complete)

Oval

Generalized thickening

Ossified or obliterated lumen

Trapped first tracheal ring

Soft stenosis

Ductal cysts

Submucosal fibrosis

Glandular hyperplasia

Granulation tissue