Joint Preservation: Care of the Older Athlete

William I. Sterett

Mark Adickes

Karen Briggs

Goals of Joint Preservation

Joint preservation in the older athlete has become more and more of an important tactic. Continued physical activity, longer life expectancies, and activity restrictions following arthroplasty have all led sports medicine physicians to get more creative about ways to preserve the native joint. Although arthroplasty components and techniques have seen recent dramatic improvements, these changes have not kept up with the increased longevity and activity levels of our maturing athletes. Joint preservation can actually be better interpreted as activity preservation techniques.

Preserving activity levels in our practice starts with understanding our patient’s activity desires. All patients come to see us with both a chief complaint and a desired activity level. Two patients may present with a current level of activity involving discomfort while walking 18 holes on a golf course. The first patient really wants to get back to skiing more aggressively or playing better singles tennis, while the second patient simply wants a little less discomfort following a round of golf. Even before we see x-rays or examine the patient, we must be contemplating different treatment strategies in these two patients. Our advice will rarely involve counseling the patient to simply give up the activity for which he or she desires pain relief. Most patients realize that if they simply give up their desired activities, their knee will no longer hurt. Having said this, realistic counseling about interventions required to decrease, but possibly not eliminate, their pain should be undertaken with the patient.

In our patient population the chief complaint is usually one of pain. Considerable time should be spent clarifying the location and extent of their pain. Questions that should be asked of all patients with chronic pain include the following:

Location of the pain. We often ask the patient to point with one finger to the predominant location, if they can.

Quality of the pain. Specifically, we ask whether the pain is sharp, stabbing, and mechanical in nature, or more of a dull achy type of pain.

Severity of the pain. Use a visual analog scale to describe the pain at its worst and typical levels.

Duration of the pain. When did it start? How did it start? Was there an injury or an insidious onset?

What previous treatments have been attempted? Most patients in this category have had previous surgery. Identify all previous interventions and diagnostics, and have a good understanding of whether each intervention helped, helped briefly, or did not help.

Is the pain getting better, worse, or staying the same? Treatment recommendations are very different for severe pain that is getting rapidly better versus pain that has been slowly getting worse during the past year.

Finally, we always ask a question regarding relief of pain. “If we were able to relieve all of the pain today, what would you be doing differently in your life?” Treatment recommendations will again be very different depending on whether the answer is simply sleeping better or running the Boston Marathon.

The goal of joint preservation is really one of activity preservation and matching treatment plans with activity expectations and desires. As patients are maintaining higher activity levels for longer periods of time, traditional thoughts about age and arthroplasty no longer necessarily apply. Our treatment regimens are dictated much more strongly by the patients’ desired activity level than by their age. The positive benefits of an ongoing exercise regimen to the overall health of an individual far outweigh any negative effects of joints “wearing down.” From nutritional supplements, exercise regimens, and viscosupplementation, to arthroscopic and realignment techniques to preserve the native joints, we are requiring more and more novel ideas to preserve our patient’s desired activity levels.

The Postmeniscectomy Knee

Without question, the most common finding in a patient needing a joint preservation algorithm is the patient who has had a partial or complete meniscectomy in the distant past. This patient often has a pre-existing or congenital varus to the knee as evidenced by the bilateral nature of the alignment. Alternatively, this may be a developmental varus secondary to the meniscectomy. With normal alignment we should be putting roughly 50% of our weight during stance on the medial side of our knee and 50% on the lateral side. With less meniscal tissue we may shift this percentage very slightly toward the medial side. Over the years, this will cause further collapse of the medial plateau, which will further change the weightbearing percentages. Once we get into this cycle, it is very difficult to escape. Once more, without a sufficient meniscus, we are concentrating this higher percentage of our weight over a smaller surface area, again wearing down the native articular cartilage further.

On initial presentation, we have often seen the knee with medial compartment arthrosis, varus malalignment, and a limited amount of meniscal tissue to protect the joint further. We now classify this as the hostile knee environment, making our choice of intra-articular procedures much more limited. Meniscus replacement surgery is not an option in the varus, degenerative knee. Chondral resurfacing options are limited only to the marrow stimulation techniques and are destined to short-term successes because of the lack of meniscus to protect any “regenerate cartilage” that may be formed, and a higher percentage of body weight being placed on this area. Our algorithms for treating this knee will always take the surrounding environment into account in deciding the best short- and long-term recommendations.

Alignment

There is no single factor that affects nonoperative and surgical prognosis more than presenting alignment. Alignment appears to play a larger role than weight, body mass index, or previous surgeries in determining the rate of articular cartilage wear.1

There does not seem to be universal agreement about the effect of congenital varus on cartilage wear in the uninjured knee. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study found that “baseline knee alignment is not associated with either incident radiographic or medial specific OA (osteoarthritis)”.2 Other magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that baseline knee angle is associated with the rate of knee cartilage loss in patients with OA.3 It appears from these studies that malalignment by itself will not wear down a knee. In OA, cartilage volume will decrease by an average of 5% per year, and this will decrease much more rapidly in the malaligned knee.4

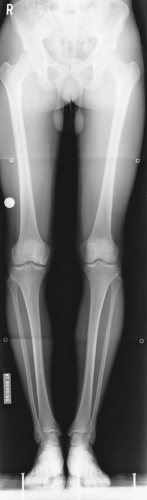

Varus alignment will predispose the knee to meniscal tears from a combination of compression and shear (Fig. 13.1). Once the knee has less meniscus, the malalignment will

more rapidly accelerate the cartilage loss than would have otherwise occurred. The malalignment itself will progress as the cartilage volume decreases and we come back to the hostile knee environment.

more rapidly accelerate the cartilage loss than would have otherwise occurred. The malalignment itself will progress as the cartilage volume decreases and we come back to the hostile knee environment.

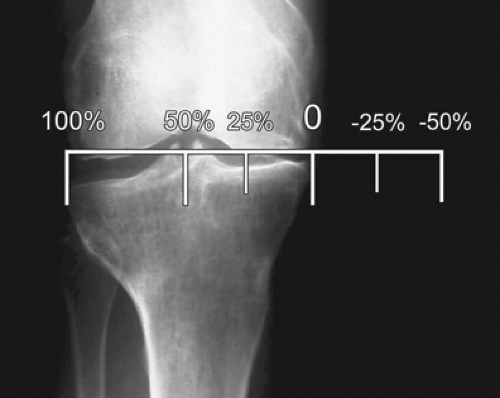

Alignment has been measured anatomically via the femorotibial angle. This may be a less exacting method for determining true weightbearing as it does not account for hip rotations, or femoral or tibial rotational or coronal malalignments. We believe that the most accurate method for determining the weightbearing characteristic at the level of the knee joint is the standing three-joint radiograph from hip to ankle (Fig. 13.2). Although variations exist, it is easiest for both surgeons and patients to understand that when a line connecting the center of the hip to the center of the ankle falls directly bicondylar in the center of the tibial plateau, we have a relatively equal weight distribution between our medial and lateral sides of the knee. As this weightbearing line (WBL) falls more medially (or possibly laterally), we are placing more and more of our weight on an isolated compartment of the knee. It is equally easy to visualize that if we are placing 70% of our weight on the portion of the knee that has less meniscus, more cartilage volume will be lost over a given time period. With articular cartilage wear, the bony hypertension that develops will create more concentrated pain and problems for the patient with a more difficult problem for the physician to solve.

The WBL can typically be reported as a percentage across the tibial plateau. When the WBL falls right in the middle, this can be reported as a WBL of 50% or 0.5. If the WBL actually falls medial to the medial plateau, this will be reported as a negative number. As the WBL falls lateral to the lateral aspect of the tibia, the WBL will be a number larger than 100% or 1.0 (Fig. 13.3).

Desired Versus Current Activity Levels

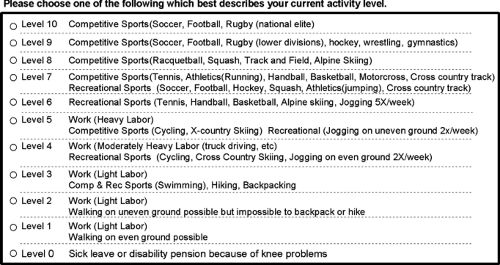

When we initially see a patient, we like to know the disease (pain) severity and activity levels for both current and desired participation. Disease severity is most often described for us using the Lysholm subjective rating system, which can be completed by the patient prior to our initial introduction.5 We use the Tegner Activity Scale to help decide treatment protocols (Fig. 13.4).6 Most patients present with a current activity score around 3 (walking in forest, light labor). If they are looking to stay at 3 but simply with less pain, joint preservation techniques are probably not

necessary. Often, more predictable outcomes with maintenance of the desired activity levels can occur with arthroplasty procedures. When the desired activity score of the patient is 6 or higher (alpine skiing, recreational tennis), it becomes more imperative to employ a joint preservation protocol. This is especially true when the patient is younger because of the high likelihood of revision arthroplasty, or even multiple revisions, being required during the lifespan of the young patient desiring higher activity scores.

necessary. Often, more predictable outcomes with maintenance of the desired activity levels can occur with arthroplasty procedures. When the desired activity score of the patient is 6 or higher (alpine skiing, recreational tennis), it becomes more imperative to employ a joint preservation protocol. This is especially true when the patient is younger because of the high likelihood of revision arthroplasty, or even multiple revisions, being required during the lifespan of the young patient desiring higher activity scores.

Figure 13.4 Tegner Activity Scale used to determine patients current activity level and desired activity level. |

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) outcomes are predictable and result in satisfied patients.7 Unfortunately, we need to treat patients, not x-rays. In the world’s literature to date, there have been no published reports of long-term follow-up in patients undergoing TKA and returning Tegner Activity Scores above 4. We all have patients following arthroplasty who return to skiing or singles tennis, but this is rarely our counsel. When a postarthroplasty patient returns to these sports, we can no longer make accurate predictions about the longevity of these implants. There is risk of early polyethylene wear with these activities as well as risk of more catastrophic sequelae such as loosening or fracture. Rather than predicting a 15-year lifespan for the implant in these active patients, much more caution in the longevity should be expressed. Joint preservation is once again recommended for those not desiring to modify their activities to gain a more predictable outcome from their arthroplasty.

Interventions

Nonoperative

From a nonoperative standpoint, quadriceps and hamstring muscle strengthening allows the knee to rely as much as possible on the musculature rather than the bony architecture for support. Providing a well-cushioned insole transfers some of that cushion at foot strike into the knee. Nutritional supplements such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are becoming increasingly popular and seem to help a percentage of the population.8,9,10

Activities in an unloader brace often identify those patients who may benefit from an osteotomy. It is unclear, radiographically or mechanically, the extent to which these braces actually unload the knees.11,12 Intermittent and judicious use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications can help break the cycle of inflammation that causes pain and more inflammation. The injectable viscosupplementations with hyaluronic acid have also become increasingly popular. It is unclear whether or not these provide benefits to the cartilage itself or have any actual long-term benefit.13

Operative

Chondral Resurfacing

It has become clear that acute chondral defects will predictably lead to further degenerative changes in the ensuing years. Therefore, even the asymptomatic chondral lesion should be treated surgically with attempts at repair or restoration. Acute chondral defects may be treated with a variety of techniques, including marrow stimulation techniques such as microfracture and auto- or allograft plugs such as mosaicplasty or osteochondral autologous transplantation.14,15,16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree