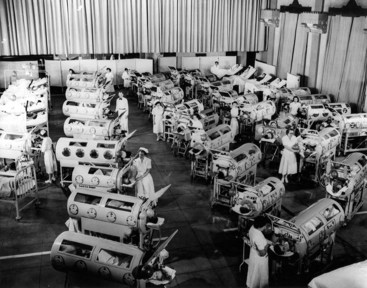

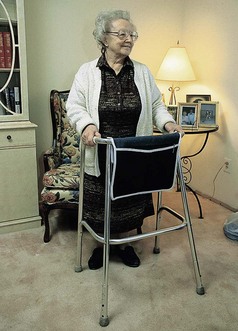

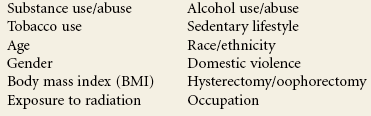

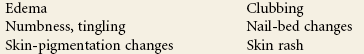

Chapter 1 As more states move toward direct access and advanced scope of practice, physical therapists are increasingly becoming the practitioner of choice and thereby the first contact that patient/clients seek,* particularly for care of musculoskeletal dysfunction. This makes it critical for physical therapists to be well versed in determining when and how referral to a physician (or other appropriate health care professional) is necessary. Each individual case must be reviewed carefully. Evidence-based clinical decision making consistent with the patient/client management model as presented in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice1 will be the foundation upon which a physical therapist’s differential diagnosis is made. Screening for systemic disease or viscerogenic causes of NMS symptoms begins with a well-developed client history and interview. The foundation for these skills is presented in Chapter 2. In addition, the therapist will rely heavily on clinical presentation and the presence of any associated signs and symptoms to alert him or her to the need for more specific screening questions and tests. Under evidence-based medicine, relying on a red-flag checklist based on the history has proved to be a very safe way to avoid missing the presence of serious disorders. Efforts are being made to validate red flags currently in use (see further discussion in Chapter 2). When serious conditions have been missed, it is not for lack of special investigations but for lack of adequate and thorough attention to clues in the history.2,3 Some conditions will be missed even with screening because the condition is early in its presentation and has not progressed enough to be recognizable. In some cases, early recognition makes no difference to the outcome, either because nothing can be done to prevent progression of the condition or there is no adequate treatment available.2 How often does it happen that a systemic or viscerogenic problem masquerades as a neuromuscular or musculoskeletal problem? There are very limited statistics to quantify how often organic disease masquerades or presents as NMS problems. Osteopathic physicians suggest this happens in approximately 1% of cases seen by physical therapists, but little data exist to confirm this estimate.4,5 At the present time, the screening concept remains a consensus-based approach patterned after the traditional medical model and research derived from military medicine (primarily case studies). Personal experience suggests the 1% figure would be higher if therapists were screening routinely. In support of this hypothesis, a systematic review of 64 cases involving physical therapist referral to physicians with subsequent diagnosis of a medical condition showed that 20% of referrals were for other concerns.6 Physical therapists involved in the cases were routinely performing screening examinations, regardless of whether or not the client was initially referred to the physical therapist by a physician. These results demonstrate the importance of therapists screening beyond the chief presenting complaint (i.e., for this group the red flags were not related to the reason physical therapy was started). For example, one client came with diagnosis of cervical stenosis. She did have neck problems, but the therapist also observed an atypical skin lesion during the postural exam and subsequently made the referral.6 Three key factors that create a need for screening are: If the medical diagnosis is delayed, then the correct diagnosis is eventually made when 1. The patient/client does not get better with physical therapy intervention. 2. The patient/client gets better then worse. There are times when a patient/client with NMS complaints is really experiencing the side effects of medications. In fact, this is probably the most common source of associated signs and symptoms observed in the clinic. Side effects of medication as a cause of associated signs and symptoms, including joint and muscle pain, will be discussed more completely in Chapter 2. Visceral pain mechanisms are the entire subject of Chapter 3. Movement, physical activity, and moderate exercise aid the body and boost the immune system,7–9 but sometimes such measures are unable to prevail, especially if other factors are present such as inadequate hydration, poor nutrition, fatigue, depression, immunosuppression, and stress. In such cases the condition will progress to the point that warning signs and symptoms will be observed or reported and/or the patient/client’s condition will deteriorate. The need for medical referral or consultation will become much more evident. There are many reasons why the therapist may need to screen for medical disease. Direct access (see definition and discussion later in this chapter) is only one of those reasons (Box 1-1). The practice of physical therapy has changed many times since it was first started with the Reconstruction Aides. Clinical practice, as it was shaped by World War I and then World War II, was eclipsed by the polio epidemic in the 1940s and 1950s. With the widespread use of the live, oral polio vaccine in 1963, polio was eradicated in the United States and clinical practice changed again (Fig. 1-1). Today, most clients seen by therapists have impairments and disabilities that are clearly NMS-related (Fig. 1-2). Most of the time, the client history and mechanism of injury point to a known cause of movement dysfunction. Fig. 1-2 (Courtesy Jim Baker, Missoula, Montana, 2005.) The aging of America has impacted general health in significant ways. “Quicker and sicker” is a term used to describe patient/clients in the current health care arena (Fig. 1-3).10 “Quicker” refers to how health care delivery has changed in the last 10 years to combat the rising costs of health care. In the acute care setting, the focus is on rapid recovery protocols. As a result, earlier mobility and mobility with more complex patients are allowed.11 Better pharmacologic management of agitation has allowed earlier and safer mobility. Hospital inpatient/clients are discharged much faster today than they were even 10 years ago. Patients are discharged from the intensive care unit (ICU) to rehab or even home. Outpatient/client surgery is much more common, with same-day discharge for procedures that would have required a much longer hospitalization in the past. Patient/clients on the medical-surgical wards of most hospitals today would have been in the ICU 20 years ago. The number of people with at least one chronic disease or disability is reaching epidemic proportions. According to the National Institute on Aging,12 79% of adults over 70 have at least one of seven potentially disabling chronic conditions (arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases, stroke, and cancer).13 The presence of multiple comorbidities emphasizes the need to view the whole patient/client and not just the body part in question. In addition, the number of people who do not have health insurance and who wait longer to seek medical attention are sicker when they access care. This factor, combined with the American lifestyle that leads to chronic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, results in a sicker population base.14 Under direct access, the physical therapist may have primary responsibility or become the first contact for some clients in the health care delivery system. On the other hand, clients may obtain a signed prescription for physical therapy from their primary care physician or other health care provider, based on similar past complaints of musculoskeletal symptoms, without actually seeing the physician or being examined by the physician (Case Example 1-1). Additionally, with the increasing specialization of medicine, clients may be evaluated by a medical specialist who does not immediately recognize the underlying systemic disease, or the specialist may assume that the referring primary care physician has ruled out other causes (Case Example 1-2). In some cases, early signs and symptoms of systemic disease may be difficult or impossible to recognize until the disease has progressed enough to create distressing or noticeable symptoms (Case Example 1-3). In some cases, the patient/client’s clinical presentation in the physician’s office may be very different from what the therapist observes when days or weeks separate the two appointments. Holidays, vacations, finances, scheduling conflicts, and so on can put delays between medical examination and diagnosis and that first appointment with the therapist. A large part of the screening process is identifying yellow (caution) or red (warning) flag histories and signs and symptoms (Box 1-2). A yellow flag is a cautionary or warning symptom that signals “slow down” and think about the need for screening. Red flags are features of the individual’s medical history and clinical examination thought to be associated with a high risk of serious disorders such as infection, inflammation, cancer, or fracture.15 A red-flag symptom requires immediate attention, either to pursue further screening questions and/or tests or to make an appropriate referral. Clusters of yellow and/or red flags do not always warrant medical referral. Each case is evaluated on its own. It is time to take a closer look when risk factors for specific diseases are present or both risk factors and red flags are present at the same time. Even as we say this, the heavy emphasis on red flags in screening has been called into question.16,17 It has been reported that in the primary care (medical) setting, some red flags have high false-positive rates and have very little diagnostic value when used by themselves.5 Efforts are being made to identify reliable red flags that are valid based on patient-centered clinical research. Whenever possible, those yellow/red flags are reported in this text.5,18,19 Medical conditions can cause pain, dysfunction, and impairment of the For the most part, the organs are located in the central portion of the body and refer symptoms to the nearby major muscles and joints. In general, the back and shoulder represent the primary areas of referred viscerogenic pain patterns. Cases of isolated symptoms will be presented in this text as they occur in clinical practice. Symptoms of any kind that present bilaterally always raise a red flag for concern and further investigation (Case Example 1-4). Monitoring vital signs is a quick and easy way to screen for medical conditions. Vital signs are discussed more completely in Chapter 4. Asking about the presence of constitutional symptoms is important, especially when there is no known cause. Constitutional symptoms refer to a constellation of signs and symptoms present whenever the patient/client is experiencing a systemic illness. No matter what system is involved, these core signs and symptoms are often present (Box 1-3). Therapists can have an active role in both primary and secondary prevention through screening and education. Primary prevention involves stopping the process(es) that lead to the development of diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, or cancer in the first place (Box 1-4). According to the Guide,1 physical therapists are involved in primary prevention by “preventing a target condition in a susceptible or potentially susceptible population through such specific measures as general health promotion efforts” [p. 33]. Risk factor assessment and risk reduction fall under this category. The term “diagnosis by the physical therapist” is language used by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). It is the policy of the APTA that physical therapists shall establish a diagnosis for each patient/client. Prior to making a patient/client management decision, physical therapists shall utilize the diagnostic process in order to establish a diagnosis for the specific conditions in need of the physical therapist’s attention.20 In keeping with advancing physical therapist practice, the current education strategic plan and Vision 2020, Diagnosis by Physical Therapists (HOD P06-97-06-19), has been updated to include ordering of tests that are performed and interpreted by other health professionals (e.g., radiographic imaging, laboratory blood work). The position now states that it is the physical therapist’s responsibility in the diagnostic process to organize and interpret all relevant data.21 The diagnostic process requires evaluation of information obtained from the patient/client examination, including the history, systems review, administration of tests, and interpretation of data. Physical therapists use diagnostic labels that identify the impact of a condition on function at the level of the system (especially the human movement system) and the level of the whole person.22 The physical therapist is qualified to make a diagnosis regarding primary NMS conditions, though we must do so in accordance with the state practice act. The profession must continue to develop the concept of human movement as a physiologic system and work to get physical therapists recognized as experts in that system.23 Whenever diagnosis is discussed, we hear this familiar refrain: diagnosis is both the process and the end result of evaluating examination data, which the therapist organizes into defined clusters, syndromes, or categories to help determine the prognosis and the most appropriate intervention strategies.1 It has been described as the decision reached as a result of the diagnostic process, which is the evaluation of information obtained from the patient/client examination.20 Whereas the physician makes a medical diagnosis based on the pathologic or pathophysiologic state at the cellular level, in a diagnosis-based physical therapist’s practice, the therapist places an emphasis on the identification of specific human movement impairments that best establish effective interventions and reliable prognoses.24 Others have supported a revised definition of the physical therapy diagnosis as: a process centered on the evaluation of multiple levels of movement dysfunction whose purpose is to inform treatment decisions related to functional restoration.25 According to the Guide, the diagnostic-based practice requires the physical therapist to integrate five elements of patient/client management (Box 1-5) in a manner designed to maximize outcomes (Fig. 1-4).

Introduction to Screening for Referral in Physical Therapy

Evidence-Based Practice

Statistics

Key Factors to Consider

Reasons to Screen

Quicker and Sicker

Signed Prescription

Medical Specialization

Progression of Time and Disease

Yellow or Red Flags

Medical Screening Versus Screening for Referral

Diagnosis by the Physical Therapist

Further Defining Diagnosis

Introduction to Screening for Referral in Physical Therapy