Chapter 1. Introduction

History and development

Orthopaedic surgeons deal with deformity, diseases of bones and joints, and injuries to the musculoskeletal system. Because these are among the commonest things to affect humankind there must always have been orthopaedic surgeons of one kind or another, even in the most primitive communities. Wherever there was a witch doctor or medicine man dealing with illness and disease, as general practitioners and physicians do now, somewhere there would have been a ‘bone setter’ treating fractures and straightening limbs.

Despite these ancient origins, the word ‘orthopaedic’ is a recent introduction derived from the title of a book published by a French physician, Nicolas Andry, in 1741: Orthopaedia, or, The Art of Correcting and Preventing Deformities in Children: By such Means, as may easily be put in Practice by Parents themselves, and all such as are Employed in Educating Children.

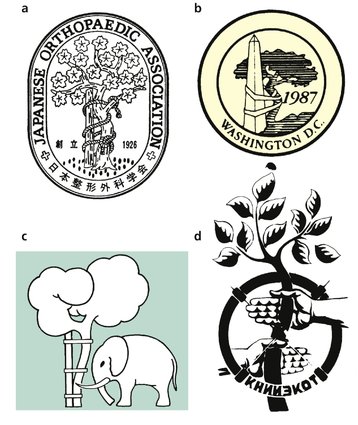

The word itself is derived from the Greek orthos pais and means only ‘straight child’, but orthopaedic surgery has expanded from the correction of deformities in children to embrace every aspect of musculoskeletal surgery. Apart from coining the word orthopaedics, Andry also designed the symbol that has now become the worldwide logo of orthopaedic surgery. The ‘Tree of Andry’ is taken from an engraving in Orthopaedia that showed a crooked tree tied to a stake in order to straighten it (Fig. 1.1). The fact that it is virtually impossible to straighten a crooked limb by tying it to a straight splint has not affected the popularity of the symbol, which has been adapted for many purposes (Fig. 1.2).

|

| Fig. 1.1 The Tree of Andry. By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London. |

|

| Fig. 1.2 (a) The emblem of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. By kind permission of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. (b) The emblem of the Eighth Combined Meeting of the Orthopaedic Associations of the English Speaking World, Washington DC, 1987. By kind permission of the American Orthopaedic Association. (c) Emblem of the Orthopaedic Department, Katholieke Universiteit, Nijmegen, by kind permission. (d) Emblem of the Kurgan Scientific Research Institute of Experimental and Clinical Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Kurgan, Russia. By kind permission of Professor G.A. Ilizarov and the Pan Union Kurgan Scientific Centre for Reconstructive Traumatology and Orthopaedics. |

In some countries, the work of the bone setter was willingly carried out by physicians, and Hippocrates himself is credited with the development of a technique for reducing dislocated shoulders which stood the test of time until general anaesthesia made it easy to overcome muscle spasm. Hippocrates is also said to have treated recurrent dislocation of the shoulder by applying a flaming torch to the axilla, but this treatment has not survived.

Physicians were not always as enlightened as Hippocrates. The bone setter, who earned his living by his ability to manipulate broken limbs, was often regarded with disfavour by the established medical profession, and this was certainly true in Britain. When the Medical Act of 1858 restricted the use of the title ‘Doctor’ to those who had passed certain recognized examinations, bone setters were excluded and became unregistered practitioners; however, this did not stop them practising, and their success remained a source of continual irritation to the medical profession. Orthopaedic hospitals existed in London and other large cities during the middle of the 19th century but they remained under the direction of registered medical practitioners.

The medical profession might have been denied access to the ‘black arts’ of the bone setters altogether if it had not been for Evan Thomas, renowned as the last of the great Welsh bone setters, who decided to put all five of his sons through medical school. One of these sons was the legendary Hugh Owen Thomas (1834–1891), who trained in Edinburgh but qualified with the London MRCS in 1857 (Fig. 1.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree