A Jones fracture of the fifth metatarsal, although named and described by Sir Robert Jones in 1902, still continues to be a source of controversy among orthopedic surgeons today. This fracture is classically located at the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction of the base of the fifth metatarsal, which extends into the intermetatarsal articulation between the fourth and fifth metatarsals (

Fig. 14.1). Jones fractures are often confused with and must be distinguished from adjacent fractures of the fifth metatarsal. The tenuous blood supply surrounding the fracture site, as well as the complex bony anatomy and curvature of the intramedullary canal, all contribute to the difficulty in managing such fractures.

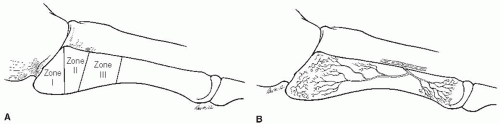

Fractures of the fifth metatarsal are most commonly classified by their anatomic location: Zone I, the tuberosity (avulsion fracture), Zone II, the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction (Jones fracture), and Zone III, distal to the articulation between the fourth and fifth metatarsals (diaphyseal stress fracture) (

Fig. 14.2A) (

1). These distinct fracture patterns are caused by varying mechanisms of injury, and therefore have individualized treatments. Jones fractures are unique because they occur in a poorly vascularized region. This watershed area, positioned between feeding vessels entering at the base of the metatarsal and the nutrient artery flowing into the diaphysis, puts it at a greater risk for a delayed union or a nonunion (

Fig. 14.2B).

Diagnosing a patient with a Jones fracture is not always straightforward. A wide spectrum of presenting symptoms has been reported, and the initial complaint may be subtle, such as intermittent soreness precipitated by minimal activity. Patients complain of pain and occasionally of swelling, localized to the lateral midfoot. They may present after an acute injury or after a more insidious onset of worsening discomfort. A significant proportion of athletes retrospectively recall pain during the several weeks prior to a particular injury; however, many are only evaluated after a specific incident that prohibits them from competing. It is when the pain interferes with the ability to walk or run that the patient in the general population tends to seek medical advice.

If acute at onset, the mechanism of injury is often described as a lateral adduction force applied with a twisting or rotational component, with the heel elevated off of the ground. An example is when a player plants and pushes off in another direction or does a “pivot-shift” maneuver.

Imaging should always support your suspicion of a Jones fracture in any athlete, until proven otherwise. Weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP), oblique (

Fig. 14.3A), and lateral radiographs are routinely obtained for further evaluation; however, x-rays may require 3 to 6 weeks before verification is noted in a chronic situation. Technetium-99 bone scintigraphy can be used as a sensitive

screening tool (

Fig. 14.3B), since positive affirmation may only take 1 to 8 days. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) adds pertinent information to further localize a fracture or investigate for bone edema, when the plain films appear normal. Computed tomography (CT) is useful in the setting of a possible refracture or an area of delayed healing or when there is metal artifact obscuring visualization (

Fig. 14.3C).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Nonoperative management remains to be the mainstay of treatment for the general nonathletic population of patients who sustain an acute Jones fracture. Historically, a non-weight-bearing cast is advocated for a period of 6 weeks, followed by a weight-bearing cast or boot for an additional 4 to 6 weeks (

2). If radiographic healing is delayed, high-energy shock wave therapy has recently been shown to be effective as an additional treatment option (

3).

Acute surgical intervention has become a popular form of treatment in attempts to expedite healing, decrease time back to work or sport, and minimize the risk of a nonunion. Although a number of operative treatments have been described, intramedullary screw fixation remains the most accepted. The indications for acute screw fixation continue to be debated, but many authors acknowledge that it is reasonable to offer surgery for certain patients: athletes with an acute fracture, military personnel, and patients with a nonunion or refracture. There is an increasing consensus that supports offering surgery to young active patients, or those who are interested in returning to recreational activity or sport at an earlier time period. Another relative indication for

intramedullary screw fixation includes patients with a cavovarus hindfoot alignment or lateral column overload, who are more prone to a nonunion or are felt to be more susceptible to recurrent fractures.

Contraindications for intramedullary fixation of a Jones fracture are few but include infection, vascular insufficiency, and significant other medical comorbidities that take precedence over treating the fracture surgically. Smoking cessation should be obligatory for the best potential outcome, but is not feasible in the acute situation.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Preoperative planning involves a thorough history and physical examination. The examiner should ask the patient about prodromal symptoms, such as pain or swelling prior to an inciting event. It is also helpful to establish whether a subacute fracture exists, by inquiring about a recent change in training or increase in activity. Making the initial diagnosis is not always straightforward, and subtle symptoms and signs need to be elicited.

On physical examination, point tenderness over the base of the fifth metatarsal as well as bone percussion may reproduce the pain. Additionally, asking the athlete to perform a one-legged hop is

a good screening tool to evaluate whether the bone can fully absorb the load and force transmitted during landing. This may be helpful to assess bone healing as well.

It is imperative to evaluate the overall alignment of the leg, ankle, and hindfoot of the patient, especially in the situation of a delayed union, nonunion or refracture. On physical examination, the alignment must be assessed in a standing position, with the patient viewed anteriorly and posteriorly. The surgeon must be astutely aware of any biomechanical abnormality, such as a subtle cavus hindfoot, which may predispose the patient to further stress along the lateral border of the midfoot and compromise the surgical results if not recognized (

4). This can be the underlying factor that increases the propensity of a nonunion or refracture, and must be addressed at the time of surgery. A vascular examination needs to be performed to confirm adequate blood supply to the foot.

Standing AP, oblique, and lateral radiographs are crucial in planning for a surgical intervention. Assessing the fracture location, gapping or displacement, and amount of sclerosis all help determine whether this is a delayed union or nonunion, rather than an acute fracture. This may impact the surgical management and determine whether the surgeon elects to open the fracture site, and/or bone graft the fracture, as a part of the surgery.

The work of Torg et al. (

2) on fifth metatarsal fractures helped to further elicit and describe the chronicity and likelihood of a delayed union or nonunion, based on radiographic findings. Their classification system (

Table 14.1) divides Jones fractures into acute (type I) showing no sclerosis and sharp edges, delayed (type II) with intramedullary sclerosis and adjacent bone resorption, and nonunion (type III) displaying complete obliteration of the canal by sclerotic bone. They supported operative intervention in types II and III, and using bone graft in those fractures with a delayed or nonunion.