Internal Impingement/SLAP Lesions

Armando F. Vidal

Kevin M. McGee

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 15 to 20 years, there has been increasing interest associated with internal impingement of the shoulder and the spectrum of pathology associated with this syndrome. The fascination surrounding internal impingement is equally distributed among sports fans and clinicians, due to its association with overhead athletes and the so-called dead arm. Shoulder problems in overhead athletes have been recognized for decades, especially in their relation to baseball pitchers. The physician’s understanding of the condition has evolved from psychopathology to external impingement to internal impingement. There is still controversy over the underlying cause of internal impingement, but the resultant spectrum of shoulder pathology is well recognized and includes posterior labral tears, SLAP tears, posterior glenoid erosion, greater tuberosity cysts, and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. There is now documentation in the literature of this spectrum of pathology in the general population, not just overhead athletes (1,2). This recognition makes the diagnosis and treatment of internal impingement all the more relevant for the orthopaedic surgeon.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOLOGY

There is some controversy in the literature regarding the essential anatomic abnormality that sets off the cascade leading to the shoulder pathology seen at arthroscopy in patients with internal impingement. The major difference in theories surrounding internal impingement is a question of laxity and glenohumeral translation. Are these shoulders too tight or too loose? There are studies to support both theories with good outcomes (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). It may be that both phenomena can lead to posterior-superior shoulder pathology. It is important to discuss these two theories because it may alter your ultimate treatment of patients with internal impingement.

Microinstability

Jobe and colleagues have described anterior instability in the overhead athlete (7, 8, 9,12). They note that there is often a continuum of instability in the throwing athlete and that it may present as occult or subtle. These authors have documented that rotator cuff injury in throwers results from increased glenohumeral motion that arises from instability (12). A subtle increase in motion can result in internal impingement of rotator cuff between the greater tuberosity and the posterosuperior glenoid. They believe that this contact leads to the spectrum of pathology seen in internal impingement. The degree and chronicity of the instability and impingement will affect the severity of injury. This is often related to the age of the athlete and how long they have been throwing or participating in overhead athletics.

Both static and dynamic stabilizers act to prevent shoulder instability. Secondary or dynamic stabilizers may be fatigued with repetitive throwing or overhead motions (serving motion in tennis and volleyball). The static stabilizers may be stretched or disrupted with a single traumatic event or, more often, through microtraumatic events associated with overhead sports. Davidson et al. (13) noted that increases in glenohumeral motion can arise from stretching of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) complex or labral tearing.

In support of the instability theory, Jobe et al. (7) reported high rates of return to competitive play in throwers who were treated with anterior capsular labral reconstruction. Levitz et al. (11) also reported favorable results when capsular laxity in throwers was addressed at time of arthroscopy. In their study, patients were divided into two groups based on treatment. The first group of baseball throwers underwent débridement and or repair of labral and rotator cuff tears. The second group underwent this same treatment plus thermal capsulorrhaphy. At 30 months after surgery, 90% of the thermal capsulorrhaphy group was back to competition compared to 67% of the débridement/repair-only group.

GIRD

Burkhart et al. (4,5) have popularized the concept of an internal rotation defect as a cause of the pathology seen with internal impingement. They propose that internal impingement is a natural phenomenon in all shoulders, a concept that is supported by Halbrecht et al. (6) and Walch et al. (2). They explain that it is actually a tightening of the posteroinferior capsule that leads to the changes seen in the posterosuperior shoulder of overhead athletes. This contracture secondarily leads to hyperexternal rotation in abduction. They gave an extensive explanation of their theory in 2003 (5). We will try to highlight the key points of their theory.

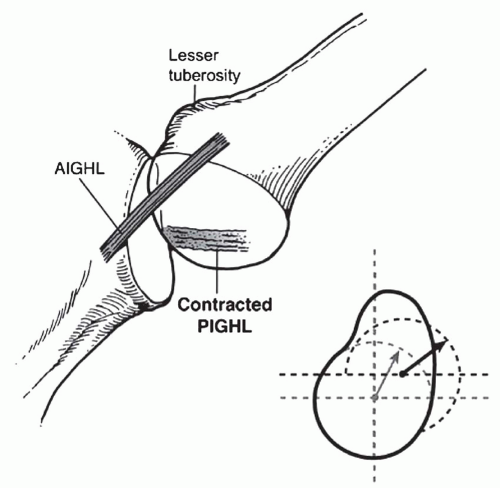

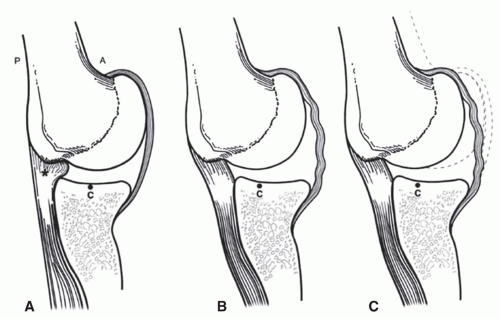

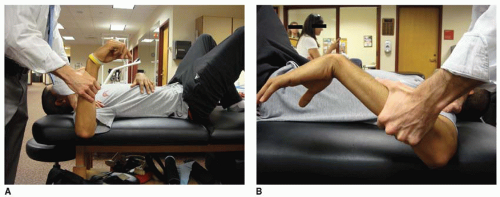

The definition of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) is the loss of internal rotation in degrees when comparing the symptomatic shoulder to the contralateral shoulder. It is measured with the shoulder in 90 degrees of abduction (Fig. 8.1). The IGHL complex functions as a hammock to stabilize the shoulder in abduction. It is composed of the posterior inferior glenohumeral ligament (PIGHL) and the anterior inferior glenohumeral ligament that act as interdependent cables. Contracture of the PIGHL can shift the center of rotation of the glenohumeral joint posterosuperiorly with the shoulder in abduction. This allows increased external rotation as the greater tuberosity can now rotate further before contacting the posterior glenoid (Fig. 8.2). This posterosuperior shift in the contact point and greater tuberosity clearance leads to a decrease in the CAM effect of the proximal humeral calcar (Fig. 8.3). Reducing the CAM effect decreased tension on the anterior capsule causing capsular redundancy. Burkhart et al. believe that this redundancy can be misinterpreted as anterior instability. A shoulder that abducts and excessively externally rotates is prone to overuse injury. The biceps anchor and posterosuperior labrum can fail due to shear forces via the peel back mechanism. The posterosuperior rotator cuff sees both increased shear and torsional stresses, which can lead to undersurface fiber failure. Thus, with time, the thrower with GIRD can develop the pathologic changes seen with internal impingement.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Physical Exam

Patients with internal impingement can have a variety of findings on physical exam. A thorough shoulder exam with comparison to the uninvolved shoulder is very important. Evaluation of range of motion, rotator cuff strength, palpation, impingement maneuvers, scapular mechanics, stability, and biceps anchor or SLAP stress tests are all part of the exam. Exam findings will vary with length and severity of symptoms. Overhead athletes

with chronic symptoms will frequently develop pain with external impingement maneuvers due to rotator cuff tendinopathy and subacromial inflammation. It is important to determine if these symptoms are secondary to internal impingement, as success with just subacromial decompression in overhead athletes is quite poor (14).

with chronic symptoms will frequently develop pain with external impingement maneuvers due to rotator cuff tendinopathy and subacromial inflammation. It is important to determine if these symptoms are secondary to internal impingement, as success with just subacromial decompression in overhead athletes is quite poor (14).

FIGURE 8.1 Severe GIRD in a collegiate tennis player. A: 0-degree internal rotation dominant shoulder. B: 60-degree internal rotation non-dominant shoulder. |

Overhead athletes, especially throwers, have characteristic adaptations with regard to range of motion. As mentioned previously, GIRD has been associated with internal impingement (4,5,15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree