Inlay Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Michael A. Rauh

John A. Bergfeld

William M. Wind

Richard D. Parker

Treatment for posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries has improved recently due in part to greater understanding of the biomechanics and pathophysiology. However, current understanding of this condition continues to lag behind that of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) due in part to the relative infrequency with which this injury is encountered. A ruptured PCL, either isolated or combined, is rare compared with other ligamentous injuries of the knee, and accounts for only 5% to 20% of ligamentous disruptions in the knee.

In addition, focused examination on the PCL with the “dial” test, posterior drawer test, and the quadriceps active test along with the development of improved imaging techniques has greatly improved the physician’s ability to provide a reliable diagnosis differentiating between an isolated PCL injury and combined injury to the PCL and other capsuloligamentous structures. Knowledge of the correct diagnosis and observation of natural history of these injuries has allowed for the development of improved treatment recommendations.

Most would agree that isolated injuries to the PCL are best treated nonoperatively with adequate results. However, the natural history of isolated injury to the PCL is still debated in the sports community. Definite episodes of instability are uncommon with chronic PCL deficiency as opposed to that feature which is commonly seen after ACL disruption. Our experience has shown a small percentage of patients with PCL deficiency is reported to experience chronic pain and may exhibit degenerative changes in the patellofemoral and medial compartments with time. Furthermore, operative treatment of isolated PCL injuries has had inconsistent results.

Nonetheless, there is a subset of patients for which reconstruction of the PCL is indicated: chronic, isolated grade 3 abnormal laxity of the PCL that has failed nonoperative treatment, as well as acute or chronic PCL injury with combined ligamentous injury. Identifying this subset of patients is the key to a successful outcome from reconstruction of the PCL.

In the past, there have been multiple surgical procedures designed to reconstruct the PCL, yet the literature reveals no long-term studies indicating normal stability following a reconstruction. Early experience with PCL surgery using a transtibial tunnel in a modified open procedure demonstrated that ligament reconstruction would result in an initially stable knee; however, there would be considerable laxity by 1-year follow-up.

Surgical options include the transtibial and posterior tibial inlay reconstructions. The transtibial method involves arthroscopic visualization of the tibial insertion of the PCL with graft passage beyond the acute or commonly referred to “killer turn” at the posterior aspect of the tibial plateau into the medial femoral condyle. With a single-bundle reconstruction, the anterolateral bundle is usually reconstructed since it is larger and stronger than the posteromedial bundle.The posterior inlay technique of PCL replacement has gained recent popularity, and it is currently the technique used for PCL reconstructions at our institutions. We feel that this technique is superior to the other methods for several reasons. First, it is believed to more closely duplicates the normal PCL anatomy. Second, it avoids the so-called “killer curve” found in the arthroscopic-assisted posterior tibial tunnel method. Biomechanical studies have demonstrated that the inlay reconstruction as well as the tibial tunnel reconstruction both provide immediate stability (11). However, these initial studies also demonstrated an area of thinning with the arthroscopic technique as the graft passed around the tibial “killer curve.” Subsequent studies demonstrated failure at this location prior to completion of cyclic loading to 2,000 cycles (11,12). Third, the operative technique is considerably easier and safer to perform although it is not an all arthroscopic procedure.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications

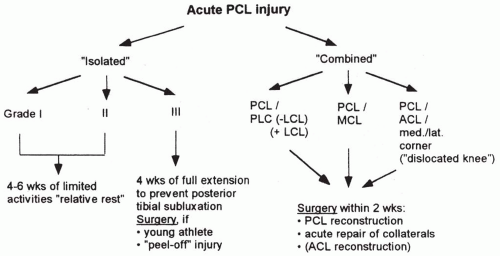

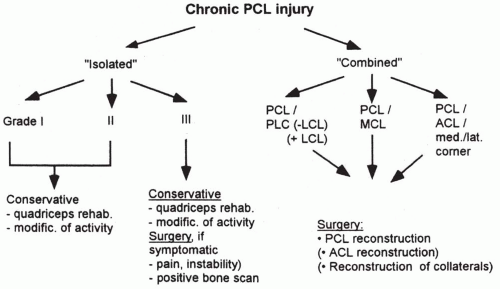

Optimal management of PCL injuries continues to be an area of debate among orthopaedic surgeons and health care professionals. Current treatment options can be clearly categorized as operative and nonoperative. Nonsurgical treatment is advocated for patients with acute isolated PCL injury, chronic isolated PCL injury in which the patient has not participated in a formal physical therapy regimen, and those injuries found in a patient who is unwilling or unable to participate in the postoperative rehabilitation program (Fig. 20-1).

Operative indications for PCL reconstruction include patients found to have “isolated” tears associated with functional disability, as well as patients with other ligamentous injuries combined with complete PCL injury (Fig. 20-2).

Some authors extend their indications to include what are termed “complete” PCL tears. Clancy and Shelbourne has classified a PCL tear as “complete” if the anterior tibial plateau recedes beyond the distal aspect of the femoral condyles on posterior drawer testing at 90 degrees of flexion. Bergfeld et al noted that if abnormal laxity with the posterior drawer test does not decrease with internal rotation of the tibia, the PCL injury is less likely to do well without surgery (2,3,4).

Two conditions which few would argue indicate for surgical intervention are:

Acute and chronic PCL injuries in combination with other capsuloligamentous injuries

Chronic grade III isolated PCL injuries that are symptomatic.

Ultimately, the decision for surgical reconstruction of the PCL is based on the activity level of the patient and whether the injury is isolated or in combination with other ligament injuries. If the posterior drawer test does not decrease with tibial internal rotation, suspicion of associated significant collateral ligament injury must be raised. Clearly, a full discussion of the injury, natural history, as well as the risks and benefits of operative and nonoperative treatment must occur with the patient before any treatment decision.

Contraindications

An acute, isolated grade I or II PCL tear

Posterior drawer test with less than 10 mm abnormal posterior laxity at 90 degrees of flexion

Posterior drawer excursion decreasing with internal rotation of the tibia with less than approximately 5 mm of abnormal posterior laxity

Less than 5 degrees of abnormal rotatory laxity

No significant varus or valgus laxity

Isolated rupture of the PCL in a patient who has not undergone a formal physical therapy program focusing on quadriceps strengthening

Knee dislocation with arterial or venous injury resulting in limb compromise

Flexion contracture greater than 10 degrees or extension contracture greater than 30 degrees

Regional pain syndrome

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History

Complete medical history and physical examination are necessary. Orthopaedic examination begins with a history of previous knee injury. Often, an individual has sustained injuries to their knees which may go unnoticed or unremembered unless the patient is specifically asked. It is important to know if the patient had issues with patellar subluxation, meniscal symptoms, or had a prior ligamentous injury. This is important as it can point the physician toward associated injuries and conditions that may alter the treatment plan. Unfortunately, patients with PCL ruptures will infrequently report feeling or hearing a “pop” as is the case with an ACL rupture.

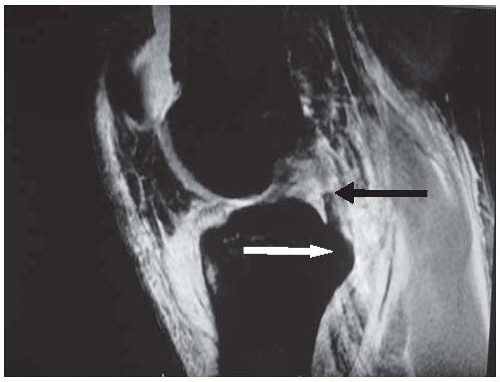

Motor vehicle accidents commonly induce PCL injuries. The knee is commonly flexed when the individual is seated in a car, and the knee is subjected to a posterior-directed force on the tibia. Similarly, the PCL can be ruptured during athletic participation through a fall on the flexed knee, with the foot plantar flexed (Fig. 20-3).

Physical Examination

The physical examination is crucial to identifying patients requiring reconstruction of the PCL. Patients with an acute isolated injury to the PCL usually present with mild to moderate effusion, and often have vague anterior or posterior soreness particularly with flexion. Patients with acute combined injuries may have a more tense effusion. Knee alignment should be noted. In cases of chronic PCL deficiency, attention to gait and lower extremity alignment is performed. Individuals demonstrating a varus alignment and varus thrust with ambulation suggest a combined PCL, posterolateral corner injury.

A complete neurovascular examination of the lower extremity is performed on all patients with suspected ligamentous injuries. Particular attention should be given to the peripheral pulses and the function of the peroneal nerve. Individuals with intact but diminished pulses or ankle-brachial indices less than 0.8 compared with the opposite extremity should undergo observation or further investigation with an angiogram based on vascular surgical consultation.

The integrity of the PCL is most accurately determined through the posterior drawer test, which is performed with the knee in 70 to 90 degrees of flexion and the tibia in neutral, external, and internal rotation. Before performing this test, the normal step-off of the anterior tibia in relation to the femur should be assessed by comparing the contralateral leg. Posterior subluxation of the tibia secondary to PCL insufficiency can give a false impression on the posterior drawer test. If this is the case, an anterior drawer should be performed first to reduce the tibia to its normal position followed by the posterior drawer. Key information is obtained by performing the posterior drawer test at 90 degrees in neutral, internal, and external rotation. An isolated injury to the PCL will show a substantial decrease in the posterior drawer with internal rotation (4). Ritchie et al found the drawer to decrease from 10 mm in neutral rotation to 4 mm with internal rotation in an isolated PCL injury. This decrease is not seen with most combined injuries. The posterior drawer test performed with external rotation, if positive, is suggestive of a combined PCL/posterolateral corner injury.

Knees with isolated Posterolateral Corner (PCL) injuries should also not exhibit increased varus or valgus laxity at 0 or 30 degrees of flexion. If present, this also suggests a combined posteromedial or posterolateral injury. Combination PCL and Posterolateral Corner (PLC) injuries are best determined by the tibial external rotation (dial) test with the knee in both 30 and 90 degrees of flexion.

Although we rely heavily on the posterior drawer test, other important tests include the quadriceps active test, posterior sag test, reverse pivot shift, external rotation recurvatum, and external tibial rotation at 0 and 30 degrees. Again, the key is to differentiate isolated from combined PCL injuries.

Radiographic Examination

Plain radiographs are the next step in evaluating PCL and knee injuries in general. We routinely include bilateral standing anteroposterior, 45-degree flexion weight bearing, Merchant patellar views, as well as a lateral view of the affected extremity. These views allow the orthopaedic physician to document pre-existing arthritis, fractures, joint spaces, knee alignment, as well as evaluate the slope of the proximal tibia. Stress radiographs can be used, with only the risk of radiation and minimal cost, to determine the sagittal translation between the injured and noninjured, presumably intact, knee.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree