Chapter 10. Injuries to the face, head and spine

Facial injuries

Facial injuries are complex, dangerous and best dealt with by faciomaxillary or plastic surgeons, but they must first be recognized in the accident department.

Nose

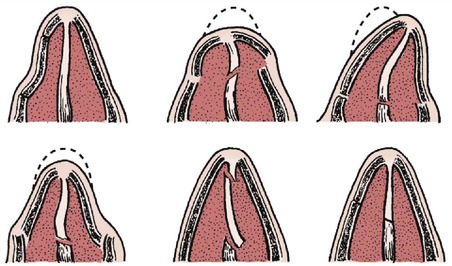

Fractures of the nasal cartilages and nasal bone are common and leave a deformity if not correctly treated. There are several different types of fracture, and not all ‘broken noses’ are the same (Fig. 10.1). If a nasal fracture is suspected, hold the patient’s nose gently and move it slightly. Pain or abnormal movement indicates a fracture.

|

| Fig. 10.1 Six types of nasal fracture. Each requires slightly different treatment and has a different prognosis. |

Treatment

Treatment depends on the pattern of the fracture. Dislocations or displaced fractures of the nasal bones need to be repositioned accurately. If a deformity is to be avoided, treatment is best carried out by facial, ENT or plastic surgeons.

Zygoma

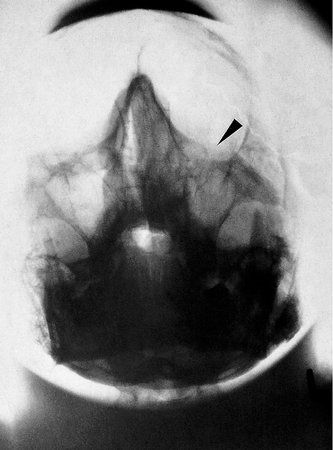

The zygoma can be fractured by a direct blow to the face and the injury is often missed because of soft tissue swelling. A depressed zygoma (Fig. 10.2) can be identified by inspecting the patient’s face from above, bearing in mind that almost every face is slightly asymmetrical, and by palpation.

|

| Fig. 10.2 A depressed zygoma with an opaque antrum. |

Untreated, a fractured zygoma leaves a flattened cheekbone, a depression in the floor of the orbit, which can result in diplopia, and damage to the infraorbital nerve. Always look for a fracture of the zygoma if there is a bruise over the cheekbone or a lateral subconjunctival haemorrhage.

Treatment

Once diagnosed, the fragment needs repositioning and sometimes fixation with wires or external fixation.

Orbital fractures

Orbital fractures are difficult to recognize but should be suspected if there has been direct trauma to the orbit or eye. A ‘blow-out’ fracture, in which the small muscles of the eye can be caught in a fracture of the floor of the orbit, is particularly serious. Diplopia and the abnormal position of the eye should lead to the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment should be carried out by facial surgeons.

Mandible

Dislocations of the temporomandibular joint can follow direct or indirect trauma, or even a wide yawn. Dislocations can usually be reduced easily, but only if the mandible is intact.

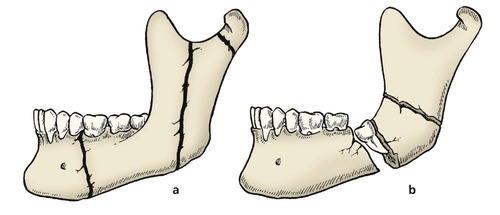

The mandible can fracture through its neck, body, symphysis or ramus (Fig. 10.3), and the fracture can be recognized by tenderness when the mandible is palpated or squeezed gently, and by a deranged dental occlusion. Fractures of the mandible often happen during a fight, sometimes after drinking. Aggressive drunks seldom like their painful jaws being palpated and the fracture can be missed. Radiographs are essential if a fractured mandible is suspected (Fig. 10.4).

|

| Fig. 10.3 Fractures of the mandible: (a) undisplaced fractures of the ramus, body and neck; (b) displaced fracture with impacted tooth. |

|

| Fig. 10.4 Fracture of the mandibular ramus ( arrowed) and the arch of the mandible caused by a blow to the point of the chin. |

Soft tissue swelling round a fractured mandible can obstruct the airway. This is particularly serious if the patient vomits and lapses into unconsciousness, as inebriated patients often do.

Treatment

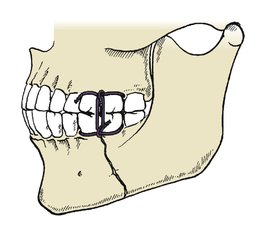

Faciomaxillary surgeons are usually responsible for treating these fractures, which may require internal fixation, interdental wiring (Fig. 10.5) or dental treatment.

|

| Fig. 10.5 Interdental wiring for fractured mandible. |

Maxilla

Le Fort classification of maxillary fractures

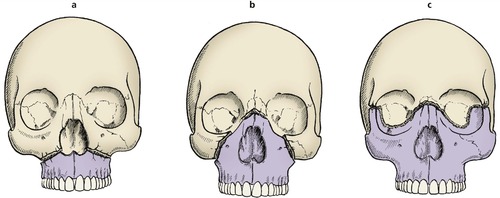

Maxillary fractures were divided into three main types by Le Fort, a French surgeon of the early 20th century who broke the faces of corpses with a cudgel to study the fracture lines. His classification is as follows (Fig. 10.6):

|

| Fig. 10.6 Le Fort facial fractures: (a) Le Fort 1; (b) Le Fort 2; (c) Le Fort 3. |

• Le Fort 1 – through the maxilla, leaving the nose and orbits intact.

• Le Fort 2 – through the maxilla into the orbits and across the nose, leaving the middle third of the face mobile.

• Le Fort 3 – through the lateral wall of the orbit and across the nose.

All maxillary fractures require urgent attention because the middle third of the face may be unstable and can fall backwards to obstruct the airway. Tracheostomy may be needed.

Because facial injuries are, by definition, head injuries, they are often seen in unconscious patients with brain damage. Always look at the maxillary antrum on the skull radiograph of patients with head injuries; if it is opaque, it is probably full of blood and there is a maxillary fracture.

Treatment

When the airway is secure, the fracture can be treated by the appropriate specialists. External fixation to the skull is often required to hold the displaced fragments in their correct position.

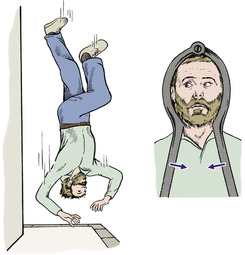

Head injuries

Injuries to the head cause brain damage, the severity of which depends on the energy absorbed by the brain and not by the skull. A skull can be crushed between two fixed objects with surprisingly little brain damage; however, rapid deceleration causing nothing more than an undisplaced linear fracture may be associated with severe brain damage (Fig. 10.7).

|

| Fig. 10.7 Brain injury and head injuries. Rapid deceleration causes more cerebral damage than a crushing fracture with little deceleration. |

Pathology

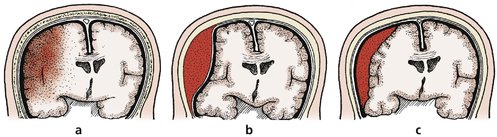

Trauma causes primary and secondary brain damage (Fig. 10.8).

|

| Fig. 10.8 Types of brain damage: (a) brain contusion with bleeding and oedema; (b) extradural haemorrhage; (c) subdural haemorrhage. |

Primary

• Contusion or laceration caused by violent impact of the brain against the skull, either at the point of injury or directly opposite to it, a contrecoup injury.

• Penetration of the skull and direct damage to the brain.

Secondary

• Oedema of the brain.

• Extradural haemorrhage.

• Subdural haemorrhage.

Clinical presentation

From a clinical standpoint, there are three main types of brain injury: concussion, contusion and compression.

Concussion

Concussion is a transient loss of consciousness following a blow to the head. Recovery is usual. The duration of amnesia following the blow is a good guide to the severity of injury. A boxer who is knocked out in a fight has concussion.

Contusion

There is damage to cerebral tissue from localized bleeding or oedema. Recovery is slower than after concussion and may be incomplete, leaving a neurological deficit.

Compression

Compression is usually caused by bleeding into the skull. As the bleeding continues, the brain is compressed and the clinical condition becomes worse. Decompression and arrest of the bleeding can be life saving.

Patients with concussion and contusion are at their worst immediately after injury and then recover. Compression causes steady deterioration instead of recovery, although there may be a lucid interval.

Management of head injuries

Distinguishing between concussion, contusion and compression depends upon careful monitoring of cerebral function. The level of consciousness and the eye signs are the most reliable clinical signs.

Level of consciousness

The level of consciousness must be recorded carefully so that any deterioration can be identified quickly. It is not enough to record that the patient is ‘awake’ or ‘unconscious’. A fully conscious patient will be alert and oriented in time and space; i.e. will know where he or she is, what time it is, and will be able to hold a normal conversation.

At the other extreme, the patient will be unrousable and not responding to painful stimuli. Between these two extremes, the level of consciousness may be graded as follows:

• Alert and oriented.

• Drowsy.

• Reacts to movement.

• Reacts to painful stimulus.

• Unrousable.

A more accurate assessment is possible with the Glasgow coma scale (Table 10.1).

| Score | ||

|---|---|---|

| Eye opening | Spontaneous | 4 |

| To voice | 3 | |

| To pain | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Verbal response | Oriented | 5 |

| Confused | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Motor response | Obeys command | 6 |

| Localizes pain | 5 | |

| Withdraw (pain) | 4 | |

| Flexion (pain) | 3 | |

| Extension (pain) | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| TOTAL | ||

| Glasgow coma scale | ||

| Score | ||

| 14–15 = 5 | ||

| 11–13 = 4 | ||

| 8–10 = 3 | ||

| 5–7 = 2 | ||

| 3–4 = 1 |

Eye signs. Raised intracranial pressure impairs the function of the iris on the side of the lesion. The size of the pupil and its reaction to light is recorded as a sign of intracranial bleeding. A fixed dilated pupil indicates an urgent problem.

Temperature. The thermoregulatory mechanism may be damaged in brain injury and the body temperature may rise. The temperature may need to be controlled by fans or tepid sponging.

Open fractures of the skull

Penetration of the skull always requires exploration by a neurological surgeon to remove dead bone, foreign matter and dead brain. Scalp wounds must not be sutured in the accident department if there is a depressed fracture under the wound.

Cerebral oedema (Fig. 10.9)

Cerebral oedema follows any major head injury and can be reduced with diuretics, such as a mannitol infusion, or by controlled hyperventilation with the patient paralysed and ventilated. This treatment is best conducted in a dedicated neurosurgical unit.

|

| Fig. 10.9 CT scan showing displacement of the midline from cerebral oedema. |

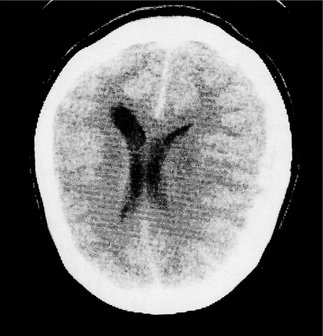

Extradural haematoma

The classic story of an extradural haematoma is the patient who walks into hospital after a minor head injury and gives a clear, sensible history. The radiograph shows a small temporal fracture. The patient is discharged home, lapses into unconsciousness and is found dead the following morning. This is a constant nightmare for those who treat head injuries. Extradural haemorrhage can be caused by damage to the middle meningeal artery. As the artery bleeds, a haematoma develops and the brain is gradually compressed. The level of consciousness slowly deteroriates until the patient becomes unrousable. If the diagnosis is made soon enough, the haematoma should be evacuated through a burr hole and the artery tied.

In days gone by, it was safer to drill burr holes than risk missing an extradural bleed but with the advent of CT scanning this complication should not take the surgeon by surprise. CT scanning is now an essential part of the management of head injuries and will show areas of brain damage as well as extradural haematomas and the position of the falx (Fig. 10.10).

|

| Fig. 10.10 CT scan showing an extradural haematoma, with shift of the midline to the opposite side. |

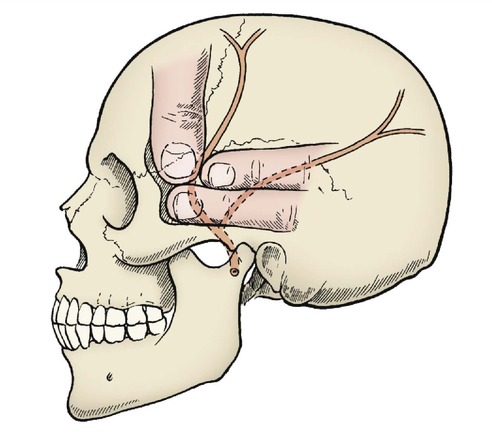

Although these investigations are reliable, ligation of the middle meningeal artery can be life saving and the correct site for the burr hole should be memorized by everyone who may be exposed to the treatment of patients with an extradural haematoma. The middle meningeal artery crosses the pterion, which lies two fingers above the zygoma and three fingers behind the orbit (also see Fig. 10.11). The artery can be found either by exposing the fracture and nibbling away the edges of the skull, or by making a burr hole at the pterion itself.

|

| Fig. 10.11 The pterion. The middle meningeal artery crosses the pterion; it can be identified with the thumb and fingers as indicated. |

Subdural haemorrhage

Acute subdural haematomas usually accumulate slowly and cause more gradual loss of consciousness than an extradural haematoma. The cause is the gradual enlargement of a blood clot beneath the dura. As the clot liquefies, serum is drawn into its centre and it gradually increases in size. A chronic subdural haematoma is not a clinical emergency but any patient whose level of consciousness deteriorates in the weeks following a head injury should have a CT scan.

Post-traumatic amnesia

The fact that a patient appears alert and oriented does not exclude brain damage. It is by no means uncommon to find that patients who have been unconscious for only a few minutes are unable to recall events for several days after their accident.

The period of post-traumatic amnesia is a reliable guide to the severity of the head injury:

1. Patients with less than 24 h post-traumatic amnesia can expect complete recovery.

2. Those with a post-traumatic amnesia of 1 week usually have some permanent impairment.

CSF rhinorrhoea and otorrhoea

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can leak from nose or ears if the fracture enters the subdural space. The leak usually ceases spontaneously but if it is profuse or persists for more than 2 weeks the defect in the dura may need to be patched with fascia.

Late sequelae

The long-term results of brain damage include continued neurological deficits, personality change, epilepsy, and serious physical disabilities requiring long-term care and rehabilitation.

Decisions in management

There are three very practical decisions in the management of head injury: when to request a skull radiograph, when to admit the patient and when to consult a neurosurgeon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree